|

Project Gutenberg

Australia a treasure-trove of literature treasure found hidden with no evidence of ownership |

BROWSE the site for other works by this author (and our other authors) or SEARCH the entire site with Google Site Search |

Title: The South Pole (Volume I.) Author: Roald Amundsen * A Project Gutenberg Australia eBook * eBook No.: e00111a.html Language: English Date first posted: January 2013 Date most recently updated: January 2013 Text file produced by Jeroen Hellingman HTML file produced by Ned Overton Project Gutenberg Australia eBooks are created from printed editions which are in the public domain in Australia, unless a copyright notice is included. We do NOT keep any eBooks in compliance with a particular paper edition. Copyright laws are changing all over the world. Be sure to check the copyright laws for your country before downloading or redistributing this file. This eBook is made available at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg Australia Licence which may be viewed online.

GO TO Project Gutenberg Australia HOME PAGE

Production Notes:

The pre-existing Project Gutenberg Australia text has been taken and compared with the scanned volumes (Chater's translation, in two volumes.) Hence here, one volume of text has become two volumes of html, with all the additions which that entails, essentially two separate tables of contents.

The main arrangement preserved in the text is the placing of the contents ahead of all of the body text, in this case "The First Account". All "--"s have been converted to "—"s. Italics have been added to all appropriate words, and all illustrations, maps and so forth and their captions have been added, with [above]: and [below]: where relevant. The index has been added to Volume 2. The few footnotes have each been moved to the end of the relevant paragraph.

THE SOUTH POLE

Frontispiece, Vol. I.??????

TRANSLATED FROM THE NORWEGIAN

BY

A. G. CHATER

WITH MAPS AND NUMEROUS ILLUSTRATIONS

IN TWO VOLUMES

VOL. I

LONDON: JOHN MURRAY

NEW YORK: LEE KEEDICK, 150 NASSAU ST

1913

TO

MY COMRADES,

THE BRAVE LITTLE BAND THAT PROMISED

IN FUNCHAL ROADS

TO STAND BY ME IN THE STRUGGLE FOR THE

SOUTH POLE,

I DEDICATE THIS BOOK.

ROALD AMUNDSEN.???

URANIENBORG,

?????August 15, 1912.

ON February 10, 1911, we started for the South to establish depots, and continued our journey until April 11. We formed three depots and stored in them 3 tons of provisions, including 22 hundredweight of seal meat. As there were no landmarks, we had to indicate the position of our depots by flags, which were posted at a distance of about four miles to the east and west. The first barrier afforded the best going, and was specially adapted for dog-sledging. Thus, on February 15 we did sixty-two miles with sledges. Each sledge weighed 660 pounds, and we had six dogs for each. The upper barrier ("barrier surface") was smooth and even. There were a few crevasses here and there, but we only found them dangerous at one or two points. The barrier went in long, regular undulations. The weather was very favourable, with calms or light winds. The lowest temperature at this station was -49° F., which was taken on March 4.

When we returned to winter quarters on February 5 from a first trip, we found that the Fram had already left us. With joy and pride we heard from those who had stayed behind that our gallant captain had succeeded in sailing her farther south than any former ship. So the good old Fram has shown the flag of Norway both farthest north and farthest south. The most southerly latitude reached by the Fram was 78° 41'.

Before the winter set in we had 60 tons of seal meat in our winter quarters; this was enough for ourselves and our 110 dogs. We had built eight kennels and a number of connecting tents and snow huts. When we had provided for the dogs, we thought of ourselves. Our little hut was almost entirely covered with snow. Not till the middle of April did we decide to adopt artificial light in the hut. This we did with the help of a Lux lamp of 200 candle-power, which gave an excellent light and kept the indoor temperature at about 68° F. throughout the winter. The ventilation was very satisfactory, and we got sufficient fresh air. The hut was directly connected with the house in which we had our workshop, larder, storeroom, and cellar, besides a single bathroom and observatory. Thus we had everything within doors and easily got at, in case the weather should be so cold and stormy that we could not venture out.

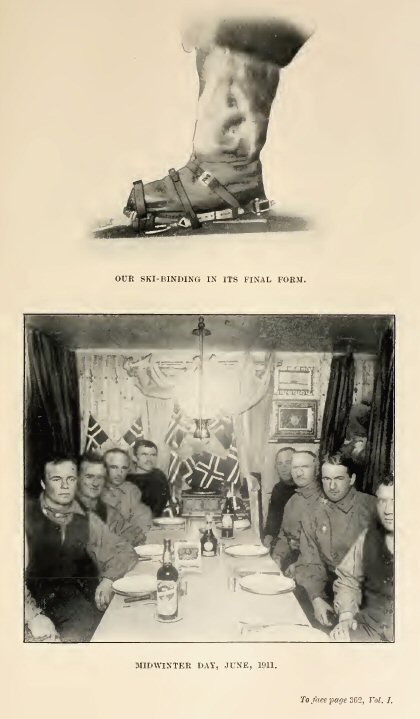

The sun left us on April 22, and we did not see it again for four months. We spent the winter in altering our whole equipment, which our depot journeys had shown to be too heavy and clumsy for the smooth barrier surface. At the same time we carried out all the scientific work for which there was opportunity. We made a number of surprising meteorological observations. There was very little snow, in spite of there being open water in the neighbourhood. We had expected to observe higher temperatures in the course of the winter, but the thermometer remained very low. During five months temperatures were observed varying between -58° and -74° F. We had the lowest (-74° F.) on August 13; the weather was calm. On August 1 we had -72° F. with a wind of thirteen miles an hour. The mean temperature for the year was -15° F. We expected blizzard after blizzard, but had only two moderate storms. We made many excellent observations of the aurora australis in all parts of the heavens. Our bill of health was the best possible throughout the whole winter. When the sun returned on August 24 it shone upon men who were healthy in mind and body, and ready to begin the task that lay before them.

We had brought the sledges the day before to the starting-point of the southern journey. At the beginning of September the temperature rose, and it was decided to commence the journey. On September 8 a party of eight men set out, with seven sledges and ninety dogs, provisioned for ninety days. The surface was excellent, and the temperature not so bad as it might have been. But on the following day we saw that we had started too early. The temperature then fell, and remained for some days between -58° and -75° F. Personally we did not suffer at all, as we had good fur clothing, but with the dogs it was another matter. They grew lanker and lanker every day, and we soon saw that they would not be able to stand it in the long run. At our depot in lat. 80° we agreed to turn back and await the arrival of spring. After having stored our provisions, we returned to the hut. Excepting the loss of a few dogs and one or two frostbitten heels, all was well. It was not till the middle of October that the spring began in earnest. Seals and birds were sighted. The temperature remained steady, between -5° and -22° F.

Meanwhile we had abandoned the original plan, by which all were to go to the south. Five men were to do this, while three others made a trip to the east, to visit King Edward VII. Land. This trip did not form part of our programme, but as the English did not reach this land last summer, as had been their intention, we agreed that it would be best to undertake this journey in addition.

On October 20 the southern party left. It consisted of five men with four sledges and fifty-two dogs, and had provisions for four months. Everything was in excellent order, and we had made up our minds to take it easy during the first part of the journey, so that we and the dogs might not be too fatigued, and we therefore decided to make a little halt on the 22nd at the depot that lay in lat. 80°. However, we missed the mark owing to thick fog, but after two or three miles' march we found the place again.

When we had rested here and given the dogs as much seal meat as they were able to eat, we started again on the 26th. The temperature remained steady, between -5° and -22° F.

At first we had made up our minds not to drive more than twelve to eighteen miles a day; but this proved to be too little, thanks to our strong and willing animals. At lat. 80° we began to erect snow beacons, about the height of a man, to show us the way home.

On the 31st we reached the depot in lat. 81°. We halted for a day and fed the dogs on pemmican. On November 5 we reached the depot in 82°, where for the last time the dogs got as much to eat as they could manage.

On the 8th we started southward again, and now made a daily march of about thirty miles. In order to relieve the heavily laden sledges, we formed a depot at every parallel we reached. The journey from lat. 82° to 83° was a pure pleasure trip, on account of the surface and the temperature, which were as favourable as one could wish. Everything went swimmingly until the 9th, when we sighted South Victoria Land and the continuation of the mountain chain, which Shackleton gives on his map, running southeast from Beardmore Glacier. On the same day we reached lat. 83°, and established here Depot No. 4.

On the 11th we made the interesting discovery that the Ross Barrier ended in an elevation on the south-east, formed between a chain of mountains running south-eastward from South Victoria Land and another chain on the opposite side, which runs south-westward in continuation of King Edward VII. Land.

On the 13th we reached lat. 84°, where we established a depot. On the 16th we got to 85°, where again we formed a depot. From our winter quarters at Framheim we had marched due south the whole time.

On November 17, in lat. 85°, we came to a spot where the land barrier intersected our route, though for the time being this did not cause us any difficulty. The barrier here rises in the form of a wave to a height of about 300 feet, and its limit is shown by a few large fissures. Here we established our main depot. We took supplies for sixty days on the sledges and left behind enough provisions for thirty days.

The land under which we now lay, and which we were to attack, looked perfectly impossible, with peaks along the barrier which rose to heights of from 2,000 to 10,000 feet. Farther south we saw more peaks, of 15,000 feet or higher.

Next day we began to climb. The first part of the work was easy, as the ground rose gradually with smooth snow-slopes below the mountain-side. Our dogs working well, it did not take us long to get over these slopes.

At the next point we met with some small, very steep glaciers, and here we had to harness twenty dogs to each sledge and take the four sledges in two journeys. Some places were so steep that it was difficult to use our ski. Several times we were compelled by deep crevasses to turn back.

On the first day we climbed 2,000 feet. The next day we crossed small glaciers, and camped at a height of 4,635 feet. On the third day we were obliged to descend the great Axel Heiberg Glacier, which separates the mountains of the coast from those farther south.

On the following day the longest part of our climbing began. Many detours had to be made to avoid broad fissures and open crevasses. Most of them were filled up, as in all probability the glacier had long ago ceased to move; but we had to be very careful, nevertheless, as we could never know the depth of snow that covered them. Our camp that night was in very picturesque surroundings, at a height of about 5,000 feet.

The glacier was here imprisoned between two mountains of 15,000 feet, which we named after Fridtjof Nansen and Don Pedro Christophersen.

At the bottom of the glacier we saw Ole Engelstad's great snow-cone rising in the air to 19,000 feet. The glacier was much broken up in this narrow defile; enormous crevasses seemed as if they would stop our going farther, but fortunately it was not so bad as it looked.

Our dogs, which during the last few days had covered a distance of nearly 440 miles, put in a very good piece of work that day, as they did twenty-two miles on ground rising to 5,770 feet. It was an almost incredible record. It only took us four days from the barrier to reach the immense inland plateau. We camped at a height of 7,600 feet. Here we had to kill twenty-four of our brave dogs, keeping eighteen—six for each of our three sledges. We halted here for four days on account of bad weather. On November 25 we were tired of waiting, and started again. On the 26th we were overtaken by a raging blizzard. In the thick, driving snow we could see absolutely nothing; but we felt that, contrary to what we had expected—namely, a further ascent—we were going rapidly downhill. The hypsometer that day showed a descent of 600 feet. We continued our march next day in a strong wind and thick, driving snow. Our faces were badly frozen. There was no danger, but we simply could see nothing. Next day, according to our reckoning, we reached lat. 86°. The hypsometer showed a fall of 800 feet. The following day passed in the same way. The weather cleared up about noon, and there appeared to our astonished eyes a mighty mountain range to the east of us, and not far away. But the vision only lasted a moment, and then disappeared again in the driving snow. On the 29th the weather became calmer and the sun shone—a pleasant surprise. Our course lay over a great glacier, which ran in a southerly direction. On its eastern side was a chain of mountains running to the southeast. We had no view of its western part, as this was lost in a thick fog. At the foot of the Devil's Glacier we established a depot in lat. 86° 21', calculated for six days. The hypsometer showed 8,000 feet above sea level. On November 30 we began to ascend the glacier. The lower part was much broken up and dangerous, and the thin bridges of snow over the crevasses often broke under us. From our camp that evening we had a splendid view of the mountains to the east. Mount Helmer Hansen was the most remarkable of them all; it was 12,000 feet high, and covered by a glacier so rugged that in all probability it would have been impossible to find foothold on it. Here were also Mounts Oskar Wisting, Sverre Hassel, and Olav Bjaaland, grandly lighted up by the rays of the sun. In the distance, and only visible from time to time through the driving mists, we saw Mount Thorvald Nilsen, with peaks rising to 15,000 feet. We could only see those parts of them that lay nearest to us. It took us three days to get over the Devil's Glacier, as the weather was unusually misty.

On December 1 we left the glacier in high spirits. It was cut up by innumerable crevasses and holes. We were now at a height of 9,370 feet. In the mist and driving snow it looked as if we had a frozen lake before us; but it proved to be a sloping plateau of ice, full of small blocks of ice. Our walk across this frozen lake was not pleasant. The ground under our feet was evidently hollow, and it sounded as if we were walking on empty barrels. First a man fell through, then a couple of dogs; but they got up again all right. We could not, of course, use our ski on this smooth-polished ice, but we got on fairly well with the sledges. We called this place the Devil's Ballroom. This part of our march was the most unpleasant of the whole trip. On December 2 we reached our greatest elevation. According to the hypsometer and our aneroid barometer we were at a height of 11,075 feet—this was in lat. 87° 51'. On December 8 the bad weather came to an end, the sun shone on us once more, and we were able to take our observations again. It proved that the observations and our reckoning of the distance covered gave exactly the same result—namely, 88° 16' S. lat. Before us lay an absolutely flat plateau, only broken by small crevices. In the afternoon we passed 88° 23', Shackleton's farthest south. We pitched our camp in 88° 25', and established our last depot—No. 10. From 88° 25' the plateau began to descend evenly and very slowly. We reached 88° 29' on December 9. On December 10, 88° 56'; December 11, 89° 15'; December 12, 89° 30'; December 13, 89° 45'.

Up to this moment the observations and our reckoning had shown a surprising agreement. We reckoned that we should be at the Pole on December 14. On the afternoon of that day we had brilliant weather—a light wind from the south-east with a temperature of -10° F. The sledges were going very well. The day passed without any occurrence worth mentioning, and at three o'clock in the afternoon we halted, as according to our reckoning we had reached our goal.

We all assembled about the Norwegian flag—a handsome silken flag—which we took and planted all together, and gave the immense plateau on which the Pole is situated the name of "King Haakon VII.'s Plateau."

It was a vast plain of the same character in every direction, mile after mile. During the afternoon we traversed the neighbourhood of the camp, and on the following day, as the weather was fine, we were occupied from six in the morning till seven in the evening in taking observations, which gave us 89° 55' as the result. In order to take observations as near the Pole as possible, we went on, as near true south as we could, for the remaining 9 kilometres. On December 16 we pitched our camp in brilliant sunshine, with the best conditions for taking observations. Four of us took observations every hour of the day—twenty-four in all. The results of these will be submitted to the examination of experts.

We have thus taken observations as near to the Pole as was humanly possible with the instruments at our disposal. We had a sextant and artificial horizon calculated for a radius of 8 kilometres.

On December 17 we were ready to go. We raised on the spot a little circular tent, and planted above it the Norwegian flag and the Fram's pennant. The Norwegian camp at the South Pole was given the name of "Polheim." The distance from our winter quarters to the Pole was about 870 English miles, so that we had covered on an average 15½ miles a day.

We began the return journey on December 17. The weather was unusually favourable, and this made our return considerably easier than the march to the Pole. We arrived at "Framheim," our winter quarters, in January, 1912, with two sledges and eleven dogs, all well. On the homeward journey we covered an average of 22½ miles a day. The lowest temperature we observed on this trip was -24° F., and the highest +23° F.

The principal result—besides the attainment of the Pole—is the determination of the extent and character of the Ross Barrier. Next to this, the discovery of a connection between South Victoria Land and, probably, King Edward VII. Land through their continuation in huge mountain-ranges, which run to the south-east and were seen as far south as lat. 88° 8', but which in all probability are continued right across the Antarctic Continent. We gave the name of "Queen Maud's Mountains" to the whole range of these newly discovered mountains, about 530 miles in length.

The expedition to King Edward VII. Land, under Lieutenant Prestrud, has achieved excellent results. Scott's discovery was confirmed, and the examination of the Bay of Whales and the Ice Barrier, which the party carried out, is of great interest. Good geological collections have been obtained from King Edward VII. Land and South Victoria Land.

The Fram arrived at the Bay of Whales on January 9, having been delayed in the "Roaring Forties" by easterly winds.

On January 16 the Japanese expedition arrived at the Bay of Whales, and landed on the Barrier near our winter quarters.

We left the Bay of Whales on January 30. We had a long voyage on account of contrary wind.

We are all in the best of health.

ROALD AMUNDSEN.???

HOBART,

????March 8, 1912.

WHEN the explorer comes home victorious, everyone goes out to cheer him. We are all proud of his achievement—proud on behalf of the nation and of humanity. We think it is a new feather in our cap, and one we have come by cheaply.

How many of those who join in the cheering were there when the expedition was fitting out, when it was short of bare necessities, when support and assistance were most urgently wanted? Was there then any race to be first? At such a time the leader has usually found himself almost alone; too often he has had to confess that his greatest difficulties were those he had to overcome at home before he could set sail. So it was with Columbus, and so it has been with many since his time.

So it was, too, with Roald Amundsen—not only the first time, when he sailed in the Gjöa with the double object of discovering the Magnetic North Pole and of making the North-West Passage, but this time again, when in 1910 he left the fjord on his great expedition in the Fram, to drift right across the North Polar Sea. What anxieties that man has gone through, which might have been spared him if there had been more appreciation on the part of those who had it in their power to make things easier! And Amundsen had then shown what stuff he was made of: both the great objects of the Gjöa's expedition were achieved. He has always reached the goal he has aimed at, this man who sailed his little yacht over the whole Arctic Ocean, round the north of America, on the course that had been sought in vain for four hundred years. If he staked his life and abilities, would it not have been natural if we had been proud of having such a man to support?

But was it so?

For a long time he struggled to complete his equipment. Money was still lacking, and little interest was shown in him and his work, outside the few who have always helped so far as was in their power. He himself gave everything he possessed in the world. But this time, as last, he nevertheless had to put to sea loaded with anxieties and debts, and, as before, he sailed out quietly on a summer night.

Autumn was drawing on. One day there came a letter from him. In order to raise the money he could not get at home for his North Polar expedition he was going to the South Pole first. People stood still—did not know what to say. This was an unheard-of thing, to make for the North Pole by way of the South Pole! To make such an immense and entirely new addition to his plans without asking leave! Some thought it grand; more thought it doubtful; but there were many who cried out that it was inadmissible, disloyal—nay, there were some who wanted to have him stopped. But nothing of this reached him. He had steered his course as he himself had set it, without looking back.

Then by degrees it was forgotten, and everyone went on with his own affairs. The mists were upon us day after day, week after week—the mists that are kind to little men and swallow up all that is great and towers above them.

Suddenly a bright spring day cuts through the bank of fog. There is a new message. People stop again and look up. High above them shines a deed, a man. A wave of joy runs through the souls of men; their eyes are bright as the flags that wave about them.

Why? On account of the great geographical discoveries, the important scientific results? Oh no; that will come later, for the few specialists. This is something all can understand. A victory of human mind and human strength over the dominion and powers of Nature; a deed that lifts us above the grey monotony of daily life; a view over shining plains, with lofty mountains against the cold blue sky, and lands covered by ice-sheets of inconceivable extent; a vision of long-vanished glacial times; the triumph of the living over the stiffened realm of death. There is a ring of steeled, purposeful human will—through icy frosts, snowstorms, and death.

For the victory is not due to the great inventions of the present day and the many new appliances of every kind. The means used are of immense antiquity, the same as were known to the nomad thousands of years ago, when he pushed forward across the snow-covered plains of Siberia and Northern Europe. But everything, great and small, was thoroughly thought out, and the plan was splendidly executed. It is the man that matters, here as everywhere.

Like everything great, it all looks so plain and simple. Of course, that is just as it had to be, we think.

Apart from the discoveries and experiences of earlier explorers—which, of course, were a necessary condition of success—both the plan and its execution are the ripe fruit of Norwegian life and experience in ancient and modern times. The Norwegians' daily winter life in snow and frost, our peasants' constant use of ski and ski-sledge in forest and mountain, our sailors' yearly whaling and sealing life in the Polar Sea, our explorers' journeys in the Arctic regions—it was all this, with the dog as a draught animal borrowed from the primitive races, that formed the foundation of the plan and rendered its execution possible—when the man appeared.

Therefore, when the man is there, it carries him through all difficulties as if they did not exist; every one of them has been foreseen and encountered in advance. Let no one come and prate about luck and chance. Amundsen's luck is that of the strong man who looks ahead.

How like him and the whole expedition is his telegram home—as simple and straightforward as if it concerned a holiday tour in the mountains. It speaks of what is achieved, not of their hardships. Every word a manly one. That is the mark of the right man, quiet and strong.

It is still too early to measure the extent of the new discoveries, but the cablegram has already dispersed the mists so far that the outlines are beginning to shape themselves. That fairyland of ice, so different from all other lands, is gradually rising out of the clouds.

In this wonderful world of ice Amundsen has found his own way. From first to last he and his companions have traversed entirely unknown regions on their ski, and there are not many expeditions in history that have brought under the foot of man so long a range of country hitherto unseen by human eye. People thought it a matter of course that he would make for Beardmore Glacier, which Shackleton had discovered, and by that route come out on to the high snow plateau near the Pole, since there he would be sure of getting forward. We who knew Amundsen thought it would be more like him to avoid a place for the very reason that it had been trodden by others. Happily we were right. Not at any point does his route touch that of the Englishmen—except by the Pole itself.

This is a great gain to research. When in a year's time we have Captain Scott back safe and sound with all his discoveries and observations on the other route, Amundsen's results will greatly increase in value, since the conditions will then be illuminated from two sides. The simultaneous advance towards the Pole from two separate points was precisely the most fortunate thing that could happen for science. The region investigated becomes so much greater, the discoveries so many more, and the importance of the observations is more than doubled, often multiplied many times. Take, for instance, the meteorological conditions: a single series of observations from one spot no doubt has its value, but if we get a simultaneous series from another spot in the same region, the value of both becomes very much greater, because we then have an opportunity of understanding the movements of the atmosphere. And so with other investigations. Scott's expedition will certainly bring back rich and important results in many departments, but the value of his observations will also be enhanced when placed side by side with Amundsen's.

An important addition to Amundsen's expedition to the Pole is the sledge journey of Lieutenant Prestrud and his two companions eastward to the unknown King Edward VII. Land, which Scott discovered in 1902. It looks rather as if this land was connected with the masses of land and immense mountain-chains that Amundsen found near the Pole. We see new problems looming up.

But it was not only these journeys over ice-sheets and mountain-ranges that were carried out in masterly fashion. Our gratitude is also due to Captain Nilsen and his men. They brought the Fram backwards and forwards, twice each way, through those ice-filled southern waters that many experts even held to be so dangerous that the Fram would not be able to come through them, and on both trips this was done with the speed and punctuality of a ship on her regular route. The Fram's builder, the excellent Colin Archer, has reason to be proud of the way in which his "child" has performed her latest task—this vessel that has been farthest north and farthest south on our globe. But Captain Nilsen and the crew of the Fram have done more than this; they have carried out a work of research which in scientific value may be compared with what their comrades have accomplished in the unknown world of ice, although most people will not be able to recognize this. While Amundsen and his companions were passing the winter in the South, Captain Nilsen, in the Fram, investigated the ocean between South America and Africa. At no fewer than sixty stations they took a number of temperatures, samples of water, and specimens of the plankton in this little-known region, to a depth of 2,000 fathoms and more. They thus made the first two sections that have ever been taken of the South Atlantic, and added new regions of the unknown ocean depths to human knowledge. The Fram's sections are the longest and most complete that are known in any part of the ocean.

Would it be unreasonable if those who have endured and achieved so much had now come home to rest? But Amundsen points onward. So much for that; now for the real object. Next year his course will be through Behring Strait into the ice and frost and darkness of the North, to drift right across the North Polar Sea—five years, at least. It seems almost superhuman; but he is the man for that, too. Fram is his ship, "forward" is his motto, and he will come through.* He will carry out his main expedition, the one that is now before him, as surely and steadily as that he has just come from.

[* Fram means "forward," "out of," "through."—TR.]

But while we are waiting, let us rejoice over what has already been achieved. Let us follow the narrow sledge-tracks that the little black dots of dogs and men have drawn across the endless white surface down there in the South—like a railroad of exploration into the heart of the unknown. The wind in its everlasting flight sweeps over these tracks in the desert of snow. Soon all will be blotted out.

But the rails of science are laid; our knowledge is richer than before.

And the light of the achievement shines for all time.

FRIDTJOF NANSEN.???

LYSAKER,

May 3, 1912.

APPROXIMATE BIRD'S-EYE VIEW, DRAWN FROM THE FIRST

TELEGRAPHIC ACCOUNT

THE OPENING OF ROALD AMUNDSEN'S MANUSCRIPT.

| "Life is a ball |

| In the hands of chance." |

BRISBANE,????????????

QUEENSLAND,??????

April 13, 1912.???

HERE I am, sitting in the shade of palms, surrounded by the most wonderful vegetation, enjoying the most magnificent fruits, and writing—the history of the South Pole. What an infinite distance seems to separate that region from these surroundings! And yet it is only four months since my gallant comrades and I reached the coveted spot.

[* This retrospective chapter has here been greatly condensed, as the ground is already covered, for English readers, by Dr. H. R. Mill's "The Siege of the South Pole," Sir Ernest Shackleton's "The Heart of the Antarctic," and other works.—TR.]

I write the history of the South Pole! If anyone had hinted a word of anything of the sort four or five years ago, I should have looked upon him as incurably mad. And yet the madman would have been right. One circumstance has followed on the heels of another, and everything has turned out so entirely different from what I had imagined.

On December 14, 1911, five men stood at the southern end of our earth's axis, planted the Norwegian flag there, and named the region after the man for whom they would all gladly have offered their lives—King Haakon VII. Thus the veil was torn aside for all time, and one of the greatest of our earth's secrets had ceased to exist.

Since I was one of the five who, on that December afternoon, took part in this unveiling, it has fallen to my lot to write—the history of the South Pole.

Antarctic exploration is very ancient. Even before our conception of the earth's form had taken definite shape, voyages to the South began. It is true that not many of the explorers of those distant times reached what we now understand by the Antarctic regions, but still the intention and the possibility were there, and justify the name of Antarctic exploration. The motive force of these undertakings was—as has so often been the case—the hope of gain. Rulers greedy of power saw in their mind's eye an increase of their possessions. Men thirsting for gold dreamed of an unsuspected wealth of the alluring metal. Enthusiastic missionaries rejoiced at the thought of a multitude of lost sheep. The scientifically trained world waited modestly in the background. But they have all had their share: politics, trade, religion, and science.

The history of Antarctic discovery may be divided at the outset into two categories. In the first of these I would include the numerous voyagers who, without any definite idea of the form or conditions of the southern hemisphere, set their course toward the South, to make what landfall they could. These need only be mentioned briefly before passing to the second group, that of Antarctic travellers in the proper sense of the term, who, with a knowledge of the form of the earth, set out across the ocean, aiming to strike the Antarctic monster—in the heart, if fortune favoured them.

We must always remember with gratitude and admiration the first sailors who steered their vessels through storms and mists, and increased our knowledge of the lands of ice in the South. People of the present day, who are so well supplied with information about the most distant parts of the earth, and have all our modern means of communication at their command, find it difficult to understand the intrepid courage that is implied by the voyages of these men.

They shaped their course toward the dark unknown, constantly exposed to being engulfed and destroyed by the vague, mysterious dangers that lay in wait for them somewhere in that dim vastness.

The beginnings were small, but by degrees much was won. One stretch of country after another was discovered and subjected to the power of man. Knowledge of the appearance of our globe became ever greater and took more definite shape. Our gratitude to these first discoverers should be profound.

And yet even to-day we hear people ask in surprise: What is the use of these voyages of exploration? What good do they do us? Little brains, I always answer to myself, have only room for thoughts of bread and butter.

—————

The first name on the roll of discovery is that of Prince Henry of Portugal, surnamed the Navigator, who is ever to be remembered as the earliest promoter of geographical research. To his efforts was due the first crossing of the Equator, about 1470.With Bartholomew Diaz another great step in advance was made. Sailing from Lisbon in 1487, he reached Algoa Bay, and without doubt passed the fortieth parallel on his southward voyage.

Vasco da Gama's voyage of 1497 is too well known to need description. After him came men like Cabral and Vespucci, who increased our knowledge, and de Gonneville, who added to the romance of exploration.

We then meet with the greatest of the older explorers, Ferdinand Magellan, a Portuguese by birth, though sailing in the service of Spain. Setting out in 1519, he discovered the connection between the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans in the strait that bears his name. No one before him had penetrated so far South—to about lat. 52° S. One of his ships, the Victoria, accomplished the first circumnavigation of the world, and thus established in the popular mind the fact that the earth was really round. From that time the idea of the Antarctic regions assumed definite shape. There must be something in the South: whether land or water the future was to determine.

In 1578 we come to the renowned English seaman, Sir Francis Drake. Though he was accounted a buccaneer, we owe him honour for the geographical discoveries he made. He rounded Cape Horn and proved that Tierra del Fuego was a great group of islands and not part of an Antarctic continent, as many had thought.

The Dutchman, Dirk Gerritsz, who took part in a plundering expedition to India in 1599 by way of the Straits of Magellan, is said to have been blown out of his course after passing the straits, and to have found himself in lat. 64° S. under high land covered with snow. This has been assumed to be the South Shetland Islands, but the account of the voyage is open to doubt.

In the seventeenth century we have the discoveries of Tasman, and towards its close English adventurers reported having reached high latitudes in the South Atlantic.

The English Astronomer Royal, Halley, undertook a scientific voyage to the South in 1699 for the purpose of making magnetic observations, and met with ice in 52° S., from which latitude he returned to the north.

The Frenchman, Bouvet (1738), was the first to follow the southern ice-pack for any considerable distance, and to bring reports of the immense, flat-topped Antarctic icebergs.

In 1756 the Spanish trading-ship Leon came home and reported high, snow-covered land in lat. 55° S. to the east of Cape Horn. The probability is that this was what we now know by the name of South Georgia. The Frenchman, Marion-Dufresne, discovered, in 1772, the Marion and Crozet Islands. In the same year Joseph de Kerguélen-Trémarec—another Frenchman—reached Kerguelen Land.

This concludes the series of expeditions that I have thought it proper to class in the first group. "Antarctica," the sixth continent itself, still lay unseen and untrodden. But human courage and intelligence were now actively stirred to lift the veil and reveal the many secrets that were concealed within the Antarctic Circle.

Captain James Cook—one of the boldest and most capable seamen the world has known—opens the series of Antarctic expeditions properly so called. The British Admiralty sent him out with orders to discover the great southern continent, or prove that it did not exist. The expedition, consisting of two ships, the Resolution and the Adventure, left Plymouth on July 13, 1772. After a short stay at Madeira it reached Cape Town on October 30. Here Cook received news of the discovery of Kerguelen and of the Marion and Crozet Islands. In the course of his voyage to the south Cook passed 300 miles to the south of the land reported by Bouvet, and thereby established the fact that the land in question—if it existed—was not continuous with the great southern continent.

On January 17, 1773, the Antarctic Circle was crossed for the first time—a memorable day in the annals of Antarctic exploration. Shortly afterwards a solid pack was encountered, and Cook was forced to return to the north. A course was laid for the newly discovered islands—Kerguelen, Marion, and the Crozets—and it was proved that they had nothing to do with the great southern land. In the course of his further voyages in Antarctic waters Cook completed the most southerly circumnavigation of the globe, and showed that there was no connection between any of the lands or islands that had been discovered and the great mysterious "Antarctica." His highest latitude (January 30, 1774) was 71° 10' S.

Cook's voyages had important commercial results, as his reports of the enormous number of seals round South Georgia brought many sealers, both English and American, to those waters, and these sealers, in turn, increased the field of geographical discovery.

In 1819 the discovery of the South Shetlands by the Englishman, Captain William Smith, is to be recorded. And this discovery led to that of the Palmer Archipelago to the south of them.

The next scientific expedition to the Antarctic regions was that despatched by the Emperor Alexander I. of Russia, under the command of Captain Thaddeus von Bellingshausen. It was composed of two ships, and sailed from Cronstadt on July 15, 1819. To this expedition belongs the honour of having discovered the first land to the south of the Antarctic Circle—Peter I. Island and Alexander I. Land.

The next star in the Antarctic firmament is the British seaman, James Weddell. He made two voyages in a sealer of 160 tons, the Jane of Leith, in 1819 and 1822, being accompanied on the second occasion by the cutter Beaufoy. In February, 1823, Weddell had the satisfaction of beating Cook's record by reaching a latitude of 74° 15' S. in the sea now known as Weddell Sea, which in that year was clear of ice.

The English firm of shipowners, Enderby Brothers, plays a not unimportant part in Antarctic exploration. The Enderbys had carried on sealing in southern waters since 1785. They were greatly interested, not only in the commercial, but also in the scientific results of these voyages, and chose their captains accordingly. In 1830 the firm sent out John Biscoe on a sealing voyage in the Antarctic Ocean with the brig Tula and the cutter Lively. The result of this voyage was the sighting of Enderby Land in lat. 66° 25' S., long. 49° 18' E. In the following year Adelaide, Biscoe, and Pitt Islands, on the west coast of Graham Land were charted, and Graham Land itself was seen for the first time.

Kemp, another of Enderby's skippers, reported land in lat. 66° S., and about long. 60° E.

In 1839 yet another skipper of the same firm, John Balleny, in the schooner Eliza Scott, discovered the Balleny Islands.

We then come to the celebrated French sailor, Admiral Jules Sébastien Dumont d'Urville. He left Toulon in September, 1837, with a scientifically equipped expedition, in the ships Astrolabe and Zélée. The intention was to follow in Weddell's track, and endeavour to carry the French flag still nearer to the Pole. Early in 1838 Louis Philippe Land and Joinville Island were discovered and named. Two years later we again find d'Urville's vessels in Antarctic waters, with the object of investigating the magnetic conditions in the vicinity of the South Magnetic Pole. Land was discovered in lat. 66° 30' S. and long. 138° 21' E. With the exception of a few bare islets, the whole of this land was completely covered with snow. It was given the name of Adélie Land, and a part of the ice-barrier lying to the west of it was called Côte Clarie, on the supposition that it must envelop a line of coast.

The American naval officer, Lieutenant Charles Wilkes, sailed in August, 1838, with a fleet of six vessels. The expedition was sent out by Congress, and carried twelve scientific observers. In February, 1839, the whole of this imposing Antarctic fleet was collected in Orange Harbour in the south of Tierra del Fuego, where the work was divided among the various vessels. As to the results of this expedition it is difficult to express an opinion. Certain it is that Wilkes Land has subsequently been sailed over in many places by several expeditions. Of what may have been the cause of this inaccurate cartography it is impossible to form any opinion. It appears, however, from the account of the whole voyage, that the undertaking was seriously conducted.

Then the bright star appears—the man whose name will ever be remembered as one of the most intrepid polar explorers and one of the most capable seamen the world has produced—Admiral Sir James Clark Ross.

The results of his expedition are well known. Ross himself commanded the Erebus and Commander Francis Crozier the Terror. The former vessel, of 370 tons, had been originally built for throwing bombs; her construction was therefore extraordinarily solid. The Terror, 340 tons, had been previously employed in Arctic waters, and on this account had been already strengthened. In provisioning the ships, every possible precaution was taken against scurvy, with the dangers of which Ross was familiar from his experience in Arctic waters.

The vessels sailed from England in September, 1839, calling at many of the Atlantic Islands, and arrived in Christmas Harbour, Kerguelen Land, in the following May. Here they stayed two months, making magnetic observations, and then proceeded to Hobart.

Sir John Franklin, the eminent polar explorer, was at that time Governor of Tasmania, and Ross could not have wished for a better one. Interested as Franklin naturally was in the expedition, he afforded it all the help he possibly could. During his stay in Tasmania Ross received information of what had been accomplished by Wilkes and Dumont d'Urville in the very region which the Admiralty had sent him to explore. The effect of this news was that Ross changed his plans, and decided to proceed along the 170th meridian E., and if possible to reach the Magnetic Pole from the eastward.

Here was another fortuitous circumstance in the long chain of events. If Ross had not received this intelligence, it is quite possible that the epoch-making geographical discoveries associated with his name would have been delayed for many years.

On November 12, 1840, Sir John Franklin went on board the Erebus to accompany his friend Ross out of port. Strange are the ways of life! There stood Franklin on the deck of the ship which a few years later was to be his deathbed. Little did he suspect, as he sailed out of Hobart through Storm Bay—the bay that is now wreathed by the flourishing orchards of Tasmania—that he would meet his death in a high northern latitude on board the same vessel, in storms and frost. But so it was.

After calling at the Auckland Islands and at Campbell Island, Ross again steered for the South, and the Antarctic Circle was crossed on New Year's Day, 1841. The ships were now faced by the ice-pack, but to Ross this was not the dangerous enemy it had appeared to earlier explorers with their more weakly constructed vessels. Ross plunged boldly into the pack with his fortified ships, and, taking advantage of the narrow leads, he came out four days later, after many severe buffets, into the open sea to the South.

Ross had reached the sea now named after him, and the boldest voyage known in Antarctic exploration was accomplished.

Few people of the present day are capable of rightly appreciating this heroic deed; this brilliant proof of human courage and energy. With two ponderous craft—regular "tubs" according to our ideas—these men sailed right into the heart of the pack, which all previous polar explorers had regarded as certain death. It is not merely difficult to grasp this; it is simply impossible—to us, who with a motion of the hand can set the screw going, and wriggle out of the first difficulty we encounter. These men were heroes—heroes in the highest sense of the word.

It was in lat. 69° 15' S. and long. 176° 15' E. that Ross found the open sea. On the following day the horizon was perfectly clear of ice. What joy that man must have felt when he saw that he had a clear way to the South!

The course was set for the Magnetic Pole, and the hope of soon reaching it burned in the hearts of all. Then—just as they had accustomed themselves to the idea of open sea, perhaps to the Magnetic Pole itself—the crow's-nest reported "High land right ahead." This was the mountainous coast of South Victoria Land.

What a fairyland this must have seemed to the first voyagers who approached it! Mighty mountain-ranges with summits from 7,000 to 10,000 feet high, some covered with snow and some quite bare—lofty and rugged, precipitous and wild.

It became apparent that the Magnetic Pole was some 500 miles distant—far inland, behind the snow-covered ridges. On the morning of January 12 they came close under a little island, and Ross with a few companions rowed ashore and took possession of the country. They could not reach the mainland itself on account of the thick belt of ice that lay along the coast.

The expedition continued to work its way southward, making fresh discoveries. On January 28 the two lofty summits, Mount Erebus and Mount Terror, were sighted for the first time. The former was seen to be an active volcano, from which smoke and flames shot up into the sky. It must have been a wonderfully fine sight, this flaming fire in the midst of the white, frozen landscape. Captain Scott has since given the island, on which the mountains lie, the name of Ross Island, after the intrepid navigator.

Naturally there were great expectations on board. If they had penetrated so far south, there might be no limit to their further progress. But, as had happened so many times before, their hopes were disappointed. From Ross Island, as far to the eastward as the eye could see, there extended a lofty, impenetrable wall of ice. To sail through it was as impossible as sailing through the cliffs of Dover, Ross says in his description. All they could do was to try to get round it. And then began the first examination of that part of the great Antarctic Barrier which has since been named the Ross Barrier.

The wall of ice was followed to the eastward for a distance of 250 miles. Its upper surface was seen to be perfectly flat. The most easterly point reached was long. 167° W., and the highest latitude 78° 4' S. No opening having been found, the ships returned to the west, in order to try once more whether there was any possibility of reaching the Magnetic Pole. But this attempt soon had to be abandoned on account of the lateness of the season, and in April, 1841, Ross returned to Hobart.

His second voyage was full of dangers and thrilling incidents, but added little to the tale of his discoveries.

On February 22, 1842, the ships came in sight of the Barrier, and, following it to the east, found that it turned north-eastward. Here Ross recorded an "appearance of land" in the very region in which Captain Scott, sixty years later, discovered King Edward VII. Land.

On December 17, 1842, Ross set out on his third and last Antarctic voyage. His object this time was to reach a high latitude along the coast of Louis Philippe Land, if possible, or alternatively by following Weddell's track. Both attempts were frustrated by the ice conditions.

On sighting Joinville Land, the officers of the Terror thought they could see smoke from active volcanoes, but Ross and his men did not confirm this. About fifty years later active volcanoes were actually discovered by the Norwegian, Captain C. A. Larsen, in the Jason. A few minor geographical discoveries were made, but none of any great importance.

This concluded Ross's attempts to reach the South Pole. A magnificent work had been achieved, and the honour of having opened up the way by which, at last, the Pole was reached must be ascribed to Ross.

The Pagoda, commanded by Lieutenant Moore, was the next vessel to make for the South. Her chief object was to make magnetic observations in high latitudes south of the Indian Ocean.

The first ice was met with in lat. 53° 30' S., on January 25, 1845. On February 5 the Antarctic Circle was crossed in long. 30° 45' E. The most southerly latitude attained on this voyage was 67° 50', in long. 39°41' E.

This was the last expedition to visit the Antarctic regions in a ship propelled by sails alone.

The next great event in the history of the southern seas is the Challenger expedition. This was an entirely scientific expedition, splendidly equipped and conducted.

The achievements of this expedition are, however, so well

known over the whole civilized world that I do not think it

necessary to dwell upon them.

Less known, but no less efficient in their work, were the whalers round the South Shetlands and in the regions to the south of them. The days of sailing-ships were now past, and vessels with auxiliary steam appear on the scene.

Before passing on to these, I must briefly mention a man who throughout his life insisted on the necessity and utility of Antarctic expeditions—Professor Georg von Neumayer.

Never has Antarctic research had a warmer, nobler, and more

high-minded champion. So long as "Antarctica" endures, the name

of Neumayer will always be connected with it.

The steam whaler Grönland left Hamburg on July 22, 1872, in command of Captain Eduard Dallmann, bound for the South Shetlands. Many interesting geographical discoveries were made on this voyage.

Amongst other whalers may be mentioned the Balæna, the Diana, the Active, and the Polar Star of Dundee.

In 1892 the whole of this fleet stood to the South to hunt for whales in the vicinity of the South Shetlands. They each brought home with them some fresh piece of information. On board the Balæna was Dr. William S. Bruce. This is the first time we meet with him on his way to the South, but it was not to be the last.

Simultaneously with the Scottish whaling fleet, the Norwegian whaling captain, C. A. Larsen, appears in the regions to the south of the South Shetlands. It is not too much to say of Captain Larsen that of all those who have visited the Antarctic regions in search of whales, he has unquestionably brought home the best and most abundant scientific results. To him we owe the discovery of large stretches of the east coast of Graham Land, King Oscar II. Land, Foyn's Land, etc. He brought us news of two active volcanoes, and many groups of islands. But perhaps the greatest interest attaches to the fossils he brought home from Seymour Island—the first to be obtained from the Antarctic regions.

In November, 1894, Captain Evensen in the Hertha succeeded in approaching nearer to Alexander I. Land than either Bellingshausen or Biscoe. But the search for whales claimed his attention, and he considered it his duty to devote himself to that before anything else.

A grand opportunity was lost: there can be no doubt that, if Captain Evensen had been free, he would here have had a chance of achieving even better work than he did—bold, capable, and enterprising as he is.

The next whaling expedition to make its mark in the South

Polar regions is that of the Antarctic, under Captain

Leonard Kristensen. Kristensen was an extraordinarily capable

man, and achieved the remarkable record of being the first to set

foot on the sixth continent, the great southern

land—"Antarctica." This was at Cape Adare, Victoria Land,

in January, 1895.

An epoch-making phase of Antarctic research is now ushered in by the Belgian expedition in the Belgica, under the leadership of Commander Adrien de Gerlache. Hardly anyone has had a harder fight to set his enterprise on foot than Gerlache. He was successful, however, and on August 16, 1897, the Belgica left Antwerp.

The scientific staff had been chosen with great care, and Gerlache had been able to secure the services of exceedingly able men. His second in command, Lieutenant G. Lecointe, a Belgian, possessed every qualification for his difficult position. It must be remembered that the Belgica's company was as cosmopolitan as it could be—Belgians, Frenchmen, Americans, Norwegians, Swedes, Rumanians, Poles, etc.—and it was the business of the second in command to keep all these men together and get the best possible work out of them. And Lecointe acquitted himself admirably; amiable and firm, he secured the respect of all.

As a navigator and astronomer he was unsurpassable, and when he afterwards took over the magnetic work he rendered great services in this department also. Lecointe will always be remembered as one of the main supports of this expedition.

Lieutenant Emile Danco, another Belgian, was the physicist of the expedition. Unfortunately this gifted young man died at an early stage of the voyage—a sad loss to the expedition. The magnetic observations were then taken over by Lecointe.

The biologist was the Rumanian, Emile Racovitza. The immense mass of material Racovitza brought home speaks better than I can for his ability. Besides a keen interest in his work, he possessed qualities which made him the most agreeable and interesting of companions.

Henryk Arçtowski and Antoine Dobrowolski were both Poles. Their share of the work was the sky and the sea; they carried out oceanographical and meteorological observations.

Henry Arçtowski was also the geologist of the expedition—an all-round man. It was a strenuous task he had, that of constantly watching wind and weather. Conscientious as he was, he never let slip an opportunity of adding to the scientific results of the voyage.

Frederick A. Cook, of Brooklyn, was surgeon to the expedition—beloved and respected by all. As a medical man, his calm and convincing presence had an excellent effect. As things turned out, the greatest responsibility fell upon Cook, but he mastered the situation in a wonderful way. Through his practical qualities he finally became indispensable. It cannot be denied that the Belgian Antarctic expedition owes a great debt to Cook.

The object of the expedition was to penetrate to the South Magnetic Pole, but this had to be abandoned at an early stage for want of time.

A somewhat long stay in the interesting channels of Tierra del Fuego delayed their departure till January 13, 1898. On that date the Belgica left Staten Island and stood to the South.

An interesting series of soundings was made between Cape Horn and the South Shetlands. As these waters had not previously been investigated, these soundings were, of course, of great importance.

The principal work of the expedition, from a geographical point of view, was carried out on the north coast of Graham Land.

A large channel running to the south-west was discovered, dividing a part of Palmer Land from the mainland—Danco's Land. The strait was afterwards named by the Belgian authorities "Gerlache Strait." Three weeks were spent in charting it and making scientific observations. An excellent collection of material was made.

This work was completed by February 12, and the Belgica left Gerlache Strait southward along the coast of Graham Land, at a date when all previous expeditions had been in a hurry to turn their faces homeward.

On the 15th the Antarctic Circle was crossed on a south-westerly course. Next day they sighted Alexander Land, but could not approach nearer to it than twenty miles on account of impenetrable pack-ice.

On February 28 they had reached lat. 70° 20' S. and long. 85° W. Then a breeze from the north sprang up and opened large channels in the ice, leading southward. They turned to the south, and plunged at haphazard into the Antarctic floes.

On March 3 they reached lat. 70° 30' S., where all further progress was hopeless. An attempt to get out again was in vain—they were caught in the trap. They then had to make the best of it.

Many have been disposed to blame Gerlache for having gone into the ice, badly equipped as he was, at a time of year when he ought rather to have been making his way out, and they may be right. But let us look at the question from the other side as well.

After years of effort he had at last succeeded in getting the expedition away. Gerlache knew for a certainty that unless he returned with results that would please the public, he might just as well never return at all. Then the thickly packed ice opened, and long channels appeared, leading as far southward as the eye could reach. Who could tell? Perhaps they led to the Pole itself. There was little to lose, much to gain; he decided to risk it.

Of course, it was not right, but we can easily understand it.

The Belgica now had thirteen long months before her. Preparations were commenced at once for the winter. As many seals and penguins as could be found were shot, and placed in store.

The scientific staff was constantly active, and brilliant oceanographical, meteorological, and magnetic work was accomplished.

On May 17 the sun disappeared, not to be seen again for seventy days. The first Antarctic night had begun. What would it bring? The Belgica was not fitted for wintering in the ice. For one thing, personal equipment was insufficient. They had to do the best they could by making clothes out of blankets, and the most extraordinary devices were contrived in the course of the winter. Necessity is the mother of invention.

On June 5 Danco died of heart-failure.

On the same day they had a narrow escape of being squeezed in the ice. Fortunately the enormous block of ice passed under the vessel and lifted her up without doing her any damage. Otherwise, the first part of the winter passed off well.

Afterwards sickness appeared, and threatened the most serious danger to the expedition—scurvy and insanity. One of them by itself would have been bad enough. Scurvy especially increased, and did such havoc that finally there was not a single man who escaped being attacked by this fearful disease.

Cook's behaviour at this time won the respect and devotion of all. It is not too much to say that Cook was the most popular man of the expedition, and he deserved it. From morning to night he was occupied with his many patients, and when the sun returned it happened not infrequently that, after a strenuous day's work, the doctor sacrificed his night's sleep to go hunting seals and penguins, in order to provide the fresh meat that was so greatly needed by all.

On July 22 the sun returned.

It was not a pleasant sight that it shone upon. The Antarctic winter had set its mark upon all, and green, wasted faces stared at the returning light.

Time went on, and the summer arrived. They waited day by day to see a change in the ice. But no; the ice they had entered so light-heartedly was not to be so easy to get out of again.

New Year's Day came and went without any change in the ice.

The situation now began to be seriously threatening. Another winter in the ice would mean death and destruction on a large scale. Disease and insufficient nourishment would soon make an end of most of the ship's company.

Again Cook came to the aid of the expedition.

In conjunction with Racovitza he had thought out a very ingenious way of sawing a channel, and thus reaching the nearest lead. The proposal was submitted to the leader of the expedition and accepted by him; both the plan and the method of carrying it out were well considered.

After three weeks' hard work, day and night, they at last reached the lead.

Cook was incontestably the leading spirit in this work, and gained such honour among the members of the expedition that I think it just to mention it. Upright, honourable, capable, and conscientious in the extreme—such is the memory we retain of Frederick A. Cook from those days.

Little did his comrades suspect that a few years later he

would be regarded as one of the greatest humbugs the world has

ever seen. This is a psychological enigma well worth studying to

those who care to do so.

But the Belgica was not yet clear of the ice. After having worked her way out into the lead and a little way on, she was stopped by absolutely close pack, within sight of the open sea.

For a whole month the expedition lay here, reaping the same experiences as Ross on his second voyage with the Erebus and Terror. The immense seas raised the heavy ice high in the air, and flung it against the sides of the vessel. That month was a hell upon earth. Strangely enough, the Belgica escaped undamaged, and steamed into Punta Arenas in the Straits of Magellan on March 28, 1899.

Modern scientific Antarctic exploration had now been

initiated, and de Gerlache had won his place for all time in the

first rank of Antarctic explorers.

While the Belgica was trying her hardest to get out of the ice, another vessel was making equally strenuous efforts to get in. This was the Southern Cross, the ship of the English expedition, under the leadership of Carstens Borchgrevink. This expedition's field of work lay on the opposite side of the Pole, in Ross's footsteps.

On February 11, 1899, the Southern Cross entered Ross Sea in lat. 70° S. and long. 174° E., nearly sixty years after Ross had left it.

A party was landed at Cape Adare, where it wintered. The ship wintered in New Zealand.

In January, 1900, the land party was taken off, and an examination of the Barrier was carried out with the vessel. This expedition succeeded for the first time in ascending the Barrier, which from Ross's day had been looked upon as inaccessible. The Barrier formed a little bight at the spot where the landing was made, and the ice sloped gradually down to the sea.

We must acknowledge that by ascending the Barrier, Borchgrevink opened a way to the south, and threw aside the greatest obstacle to the expeditions that followed. The Southern Cross returned to civilization in March, 1900.

The Valdivia's expedition, under Professor Chun, of Leipzig, must be mentioned, though in our day it can hardly be regarded as an Antarctic expedition. On this voyage the position of Bouvet Island was established once for all as lat. 54° 26' S., long. 3° 24' E.

The ice was followed from long. 8° E. to 58° E., as closely as the vessel could venture to approach. Abundance of oceanographical material was brought home.

Antarctic exploration now shoots rapidly ahead, and the twentieth century opens with the splendidly equipped British and German expeditions in the Discovery and the Gauss, both national undertakings.

Captain Robert F. Scott was given command of the Discovery's expedition, and it could not have been placed in better hands.

The second in command was Lieutenant Armitage, who had taken part in the Jackson-Harmsworth North Polar expedition.

The other officers were Royds, Barne, and Shackleton.

Lieutenant Skelton was chief engineer and photographer to the expedition. Two surgeons were on board—Dr. Koettlitz, a former member of the Jackson-Harmsworth expedition, and Dr. Wilson. The latter was also the artist of the expedition. Bernacchi was the physicist, Hodgson the biologist, and Ferrar the geologist.

On August 6, 1901, the expedition left Cowes, and arrived at Simon's Bay on October 3. On the 14th it sailed again for New Zealand.

The official plan was to determine as accurately as possible the nature and extent of the South Polar lands that might be found, and to make a magnetic survey. It was left to the leader of the expedition to decide whether it should winter in the ice.

It was arranged beforehand that a relief ship should visit and communicate with the expedition in the following year.

The first ice was met with in the neighbourhood of the Antarctic Circle on January 1, 1902, and a few days later the open Ross Sea was reached. After several landings had been made at Cape Adare and other points, the Discovery made a very interesting examination of the Barrier to the eastward. At this part of the voyage King Edward VII. Land was discovered, but the thick ice-floes prevented the expedition from landing. On the way back the ship entered the same bight that Borchgrevink had visited in 1900, and a balloon ascent was made on the Barrier. The bay was called Balloon Inlet.

From here the ship returned to McMurdo Bay, so named by Ross. Here the Discovery wintered, in a far higher latitude than any previous expedition. In the course of the autumn it was discovered that the land on which the expedition had its winter quarters was an island, separated from the mainland by McMurdo Sound. It was given the name of Ross Island.

Sledge journeys began with the spring. Depots were laid down, and the final march to the South was begun on November 2, 1902, by Scott, Shackleton, and Wilson.

They had nineteen dogs to begin with. On November 27 they passed the 80th parallel. Owing to the nature of the ground their progress was not rapid; the highest latitude was reached on December 30—82° 17' S. New land was discovered—a continuation of South Victoria Land. One summit after another rose higher and higher to the south.

The return journey was a difficult one. The dogs succumbed one after another, and the men themselves had to draw the sledges. It went well enough so long as all were in health; but suddenly Shackleton was incapacitated by scurvy, and there were only two left to pull the sledges.

On February 3 they reached the ship again, after an absence of ninety-three days.

Meanwhile Armitage and Skelton had reached, for the first time in history, the high Antarctic inland plateau at an altitude of 9,000 feet above the sea.

The relief ship Morning had left Lyttelton on December 9. On her way south Scott Island was discovered, and on January 25 the Discovery's masts were seen. But McMurdo Sound lay icebound all that year, and the Morning returned home on March 3.

The expedition passed a second winter in the ice, and in the following spring Captain Scott led a sledge journey to the west on the ice plateau. In January, 1904, the Morning returned, accompanied by the Terra Nova, formerly a Newfoundland sealing vessel. They brought orders from home that the Discovery was to be abandoned if she could not be got out. Preparations were made for carrying out the order, but finally, after explosives had been used, a sudden break-up of the ice set the vessel free.

All the coal that could be spared was put on board the Discovery from the relief ships, and Scott carried his researches further. If at that time he had had more coal, it is probable that this active explorer would have accomplished even greater things than he did. Wilkes's "Ringgold's Knoll" and "Eld's Peak" were wiped off the map, and nothing was seen of "Cape Hudson," though the Discovery passed well within sight of its supposed position.

On March 14 Scott anchored in Ross Harbour, Auckland Islands.

With rich results, the expedition returned home in September,

1904.

Meanwhile the German expedition under Professor Erich von Drygalski had been doing excellent work in another quarter.

The plan of the expedition was to explore the Antarctic regions to the south of Kerguelen Land, after having first built a station on that island and landed a scientific staff, who were to work there, while the main expedition proceeded into the ice. Its ship, the Gauss, had been built at Kiel with the Fram as a model.

The Gauss's navigator was Captain Hans Ruser, a skilful seaman of the Hamburg-American line.

Drygalski had chosen his scientific staff with knowledge and care, and it is certain that he could not have obtained better assistants.

The expedition left Kiel on August 11, 1901, bound for Cape Town. An extraordinarily complete oceanographical, meteorological, and magnetic survey was made during this part of the voyage.

After visiting the Crozet Islands, the Gauss anchored in Royal Sound, Kerguelen Land, on December 31. The expedition stayed here a month, and then steered for the south to explore the regions between Kemp Land and Knox Land. They had already encountered a number of bergs in lat. 60° S.

On February 14 they made a sounding of 1,730 fathoms near the supposed position of Wilkes's Termination Land. Progress was very slow hereabout on account of the thick floes.

Suddenly, on February 19, they had a sounding of 132 fathoms, and on the morning of February 21 land was sighted, entirely covered with ice and snow. A violent storm took the Gauss by surprise, collected a mass of icebergs around her, and filled up the intervening space with floes, so that there could be no question of making any way. They had to swallow the bitter pill, and prepare to spend the winter where they were.

Observatories were built of ice, and sledge journeys were undertaken as soon as the surface permitted. They reached land in three and a half days, and there discovered a bare mountain, about 1,000 feet high, fifty miles from the ship. The land was named Kaiser Wilhelm II. Land, and the mountain the Gaussberg.

They occupied the winter in observations of every possible kind. The weather was extremely stormy and severe, but their winter harbour, under the lee of great stranded bergs, proved to be a good one. They were never once exposed to unpleasant surprises.

On February 8, 1903, the Gauss was able to begin to move again. From the time she reached the open sea until her arrival at Cape Town on June 9, scientific observations were continued.

High land had been seen to the eastward on the bearing of Wilkes's Termination Land, and an amount of scientific work had been accomplished of which the German nation may well be proud. Few Antarctic expeditions have had such a thoroughly scientific equipment as that of the Gauss, both as regards appliances and personnel.

The Swedish Antarctic expedition under Dr. Otto Nordenskjöld left Gothenburg on October 16, 1901, in the Antarctic, commanded by Captain C. A. Larsen, already mentioned. The scientific staff was composed of nine specialists.

After calling at the Falkland Islands and Staten Island, a course was made for the South Shetlands, which came in sight on January 10, 1902.

After exploring the coast of Louis Philippe Land, the ship visited Weddell Sea in the hope of getting southward along King Oscar II. Land, but the ice conditions were difficult, and it was impossible to reach the coast.

Nordenskjöld and five men were then landed on Snow Hill Island, with materials for an observatory and winter quarters and the necessary provisions. The ship continued her course northward to the open sea.

The first winter on Snow Hill Island was unusually stormy and cold, but during the spring several interesting sledge journeys were made. When summer arrived the Antarctic did not appear, and the land party were obliged to prepare for a second winter. In the following spring, October, 1903, Nordenskjöld made a sledge journey to explore the neighbourhood of Mount Haddington, and a closer examination showed that the mountain lay on an island. In attempting to work round this island, he one day stumbled upon three figures, doubtfully human, which might at first sight have been taken for some of our African brethren straying thus far to the south.

It took Nordenskjöld a long time to recognize in these beings Dr. Gunnar Andersson, Lieutenant Duse, and their companion during the winter, a Norwegian sailor named Grunden.

The way it came about was this. The Antarctic had made repeated attempts to reach the winter station, but the state of the ice was bad, and they had to give up the idea of getting through. Andersson, Duse and Grunden were then landed in the vicinity, to bring news to the winter quarters as soon as the ice permitted them to arrive there. They had been obliged to build themselves a stone hut, in which they had passed the winter.

This experience is one of the most interesting one can read of in the history of the Polar regions. Badly equipped as they were, they had to have recourse, like Robinson Crusoe, to their inventive faculties. The most extraordinary contrivances were devised in the course of the winter, and when spring came the three men stepped out of their hole, well and hearty, ready to tackle their work.

This was such a remarkable feat that everyone who has some knowledge of Polar conditions must yield them his admiration. But there is more to tell.

On November 8, when both parties were united at Snow Hill, they were unexpectedly joined by Captain Irizar, of the Argentine gunboat Uruguay, and one of his officers. Some anxiety had been felt owing to the absence of news of the Antarctic, and the Argentine Government had sent the Uruguay to the South to search for the expedition. But what in the world had become of Captain Larsen and the Antarctic? This was the question the others asked themselves.

The same night—it sounds almost incredible—there was a knock at the door of the hut, and in walked Captain Larsen with five of his men. They brought the sad intelligence that the good ship Antarctic was no more. The crew had saved themselves on the nearest island, while the vessel sank, severely damaged by ice.

They, too, had had to build themselves a stone hut and get through the winter as best they could. They certainly did not have an easy time, and I can imagine that the responsibility weighed heavily on him who had to bear it. One man died; the others came through it well.

Much of the excellent material collected by the expedition was lost by the sinking of the Antarctic, but a good deal was brought home.

Both from a scientific and from a popular point of view this

expedition may be considered one of the most interesting the

South Polar regions have to show.

We then come to the Scotsman, Dr. William S. Bruce, in the Scotia.

We have met with Bruce before: first in the Balæna in 1892, and afterwards with Mr. Andrew Coats in Spitzbergen. The latter voyage was a fortunate one for Bruce, as it provided him with the means of fitting out his expedition in the Scotia to Antarctic waters.

The vessel left the Clyde on November 2, 1902, under the command of Captain Thomas Robertson, of Dundee. Bruce had secured the assistance of Mossman, Rudmose Brown and Dr. Pirie for the scientific work. In the following February the Antarctic Circle was crossed, and on the 22nd of that month the ship was brought to a standstill in lat. 70° 25' S. The winter was spent at Laurie Island, one of the South Orkneys.

Returning to the south, the Scotia reached, in March,

1904, lat. 74° 1' S., long. 22° W., where the sea rapidly

shoaled to 159 fathoms. Further progress was impossible owing to

ice. Hilly country was sighted beyond the barrier, and named

"Coats Land," after Bruce's chief supporters.

In the foremost rank of the Antarctic explorers of our time stands the French savant and yachtsman, Dr. Jean Charcot. In the course of his two expeditions of 1903—1905 and 1908—1910 he succeeded in opening up a large extent of the unknown continent. We owe to him a closer acquaintance with Alexander I. Land, and the discovery of Loubet, Fallières and Charcot Lands is also his work.

His expeditions were splendidly equipped, and the scientific

results were extraordinarily rich. The point that compels our

special admiration in Charcot's voyages is that he chose one of

the most difficult fields of the Antarctic zone to work in. The

ice conditions here are extremely unfavourable, and navigation in

the highest degree risky. A coast full of submerged reefs and a

sea strewn with icebergs was what the Frenchmen had to contend

with. The exploration of such regions demands capable men and

stout vessels.