|

Project Gutenberg

Australia a treasure-trove of literature treasure found hidden with no evidence of ownership |

BROWSE the site for other works by this author (and our other authors) or SEARCH the entire site with Google Site Search |

Title: Northmost Australia Author: Robert Logan Jack * A Project Gutenberg of Australia eBook * eBook No.: 0601141h.html Language: English Date first posted: June 2006 Date most recently updated: May 2013 Production notes: 1. Page numbers are at the TOP of each page. Project Gutenberg of Australia eBooks are created from printed editions which are in the public domain in Australia, unless a copyright notice is included. We do NOT keep any eBooks in compliance with a particular paper edition. Copyright laws are changing all over the world. Be sure to check the copyright laws for your country before downloading or redistributing this file. This eBook is made available at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg of Australia License which may be viewed online at http://gutenberg.net.au/licence.html To contact Project Gutenberg of Australia go to http://gutenberg.net.au

NOTE:

This ebook comprises Volumes 1 and 2 of Northmost Australia by Robert Logan Jack.

An updated version has been produced in which the 2 volumes have been separated,

all maps have been included for both volumes and high resolution versions

of the maps are available. Searchable indexes have been added and footnotes have

been moved to the end of the paragraph in which the reference to the footnote appears.

Volumes 1 and 2 of the updated version can be accessed from

Robert Logan Jack's listing at Project Gutenberg Australia.

I. INTRODUCTION

II. AUSTRALIA DISTINCT FROM NEW GUINEA. MAGELHAEN, QUIROS

AND TORRES

III. VOYAGE OF THE "DUYFKEN" TO NEW GUINEA AND THE CAPE

YORK PENINSULA, 1605-6

IV. THE VOYAGE OF THE "PERA" AND "AERNEM," 1623: I. THE

SAILING ORDERS

V. THE VOYAGE OF THE "PERA" AND "AERNEM," 1623,

continued: II. GENERAL OBSERVATIONS ON THE EXPEDITION AND ON THE "PERA"

NARRATIVE

VI. THE VOYAGE OF THE "PERA" AND "AERNEM," 1623,

continued: III. THE OUTWARD VOYAGE

VII. THE VOYAGE OF THE "PERA" AND "AERNEM," 1623,

continued: IV. THE RETURN VOYAGE OF THE "PERA"

VIII. THE VOYAGE OF THE "PERA" AND "AERNEM," 1623,

continued: V. THE "AERNEM"

IX. TASMAN'S VOYAGE OF 1644

X. VOYAGES OF THE "BUIJS" AND "RIJDER," 1756: VAN ASSCHENS

AND GONZAL

XI. COOK IN "ENDEAVOUR," 1770

XII. QUIROS, TORRES AND COOK AND THE VAUGONDY AND DALRYMPLE

MAPS

XIII. BLIGH: VOYAGE OF "BOUNTY'S" LAUNCH, 1789

XIV. THE VOYAGE OF THE "PANDORA," 1791: EDWARD EDWARDS

XV. BLIGH, 1788-92, continued: SECOND VOYAGE THROUGH

TORRES STRAIT WITH THE "PROVIDENCE" AND "ASSISTANT," 1792

XVI. THE "HORMUZEER" AND "CHESTERFIELD" (BAMPTON AND ALT),

1793

XVII. FLINDERS, 1791-1814: EARLY LIFE AND VOYAGE TO

AUSTRALIA IN THE "INVESTIGATOR," 1801-2

XVIII. FLINDERS, continued: WITH THE "INVESTIGATOR"

FROM SYDNEY TO THE GULF OF CARPENTARIA, 1802

XIX. FLINDERS, continued: "INVESTIGATOR'S" RETURN TO

SYDNEY, 1802-3

XX. FLINDERS, continued: WITH THE "CUMBERLAND" TO

TORRES STRAIT, 1803—CAPTIVITY AT MAURITIUS, 1803-10, AND CLOSE OF HIS

CAREER

XXI. PHILLIP PARKER KING IN THE "MERMAID," 1819, AND IN THE

"BATHURST," l821

XXII. WRECK OF THE "CHARLES EATON," 1834, AND SEARCH FOR

SURVIVORS, 1836

XXIII. H.M.S. "BEAGLE," WICKHAM AND STOKES, 1839-41: THE

NORMAN RIVER AND NORMANTON AND THE ALBERT RIVER AND BURKETOWN

XXIV. "L'ASTROLABE" AND "LA ZÈLÉE," 1840:

DUMONT-D'URVILLE

XXV. BLACKWOOD AND YULE, 1843-5—H.M.SS. "FLY,"

"BRAMBLE" AND "PRINCE GEORGE" AND THE PINNACE "MIDGE"

XXVI. LEICHHARDT'S OVERLAND EXPEDITION: FROM BRISBANE TO

PORT ESSINGTON, 1844-5—BRISBANE TO THE LYND RIVER

XXVII. LEICHHARDT'S OVERLAND EXPEDITION, 1844-5,

continued: THE LYND VALLEY.

XXVIII. LEICHHARDT'S OVERLAND EXPEDITION, 1844-5,

continued

XXIX. LEICHHARDT'S OVERLAND EXPEDITION, 1844-5,

continued

XXX. KENNEDY'S EXPEDITION, 1848: THE EAST COAST AND THE

COAST RANGE

XXXI. KENNEDY'S EXPEDITION, 1848, continued: FROM

THE COAST RANGE TO THE PALMER

XXXII. KENNEDY'S EXPEDITION, 1848, continued: FROM

THE PALMER TO THE PASCOE

XXXIII. KENNEDY'S EXPEDITION, 1848, continued: THE

FORLORN HOPE—FROM THE PASCOE TO CAPE YORK

XXXIV. KENNEDY'S EXPEDITION, 1848, continued: VOYAGE

OF THE "ARIEL"—TRACES OF KENNEDY AND THE "PUDDING-PAN HILL" PARTY

XXXV. KENNEDY'S EXPEDITION, 1848, continued: VOYAGE

OF THE "FREAK"—SEARCH FOR RELICS OF KENNEDY AND THE "PUDDING-PAN HILL"

PARTY

XXXVI. KENNEDY'S EXPEDITION, 1848, continued:

CARRON'S PARTY AT THE PASCOE RIVER

XXXVII. H.M.SS. "RATTLESNAKE" AND "BRAMBLE," 1847-50:

STANLEY AND YULE

XXXVIII. THE NORTH AUSTRALIAN EXPLORING EXPEDITION, 1855-6:

GREGORY

XXXIX. THE BURKE AND WILLS EXPEDITION, 1860-61

XL. BURKE AND WILLS SEARCH PARTIES IN QUEENSLAND:

LANDSBOROUGH, WALKER AND McKiNLAY, 1861-2

XLI. THE JOURNEY OF FRANK AND ALEXANDER JARDINE, 1864-5:

FROM ROCKHAMPTON TO SOMERSET—CARPENTARIA DOWNS, via EINASLEIGH

RIVER, TO THE MOUTH OF THE ETHERIDGE RIVER

XLII. THE JARDINE BROTHERS' EXPEDITION, 1864-5,

continued: FROM THE EINASLEIGH RIVER TO THE MOUTH OF THE STATEN RIVER,

DE FACTO

XLIII. THE JARDINE BROTHERS' EXPEDITION, continued:

STATEN RIVER, DE FACTO, TO JARDINE RIVER

XLIV. THE JARDINE BROTHERS' EXPEDITION, continued:

THE JARDINE RIVER AND THE PROBLEM OF THE ESCAPE RIVER

XLV. THE JARDINE BROTHERS' EXPEDITION, continued:

RECONNAISSANCE BY THE BROTHERS AND EULAH

XLVI. THE JARDINE BROTHERS' EXPEDITION,

continued

XLVII. SOMERSET AND ITS BACKGROUND

XLVIII. DAINTREE, 1863-71

XLIX. MORESBY: FIRST CRUISE OF THE "BASILISK" TO TORRES

STRAIT, 1871

L. MORESBY, continued: SECOND CRUISE OF THE

"BASILISK" IN TORRES STRAIT, 1873

LI. ABORIGINAL AND POLYNESIAN LABOUR

LII. WILLIAM HANN'S EXPEDITION, 1872: FROM FOSSILBROOK,

DOWN THE LYND RIVER AND ACROSS THE TATE AND WALSH TO LEICHHARDT'S MITCHELL

RIVER

LIII. WILLIAM HANN'S EXPEDITION, CONTINUED: EXCURSIONS IN

THE VALLEY OF THE MITCHELL AND THE RELATIONS OF THAT RIVER TO THE WALSH AND

LYND RIVERS

LIV. WILLIAM HANN'S EXPEDITION, CONTINUED: THE PALMER RIVER

AND THE DISCOVERY OF GOLD

LV. WILLIAM HANN'S EXPEDITION, CONTINUED: PALMER RIVER TO

PRINCESS CHARLOTTE BAY

LVI. WILLIAM HANN'S EXPEDITION, 1872, CONTINUED: THE RETURN

JOURNEY—PRINCESS CHARLOTTE BAY TO THE MOUTH OF THE ANNAN

RIVER—COOKTOWN

LVII. WILLIAM HANN'S EXPEDITION, CONTINUED: THE RETURN

JOURNEY—ANNAN, BLOMFIELDAND DAINTREE RIVERS

LVIII. WILLIAM HANN'S EXPEDITION, CONTINUED: THE RETURN

JOURNEY—FROM THE DAINTREE RIVER TO FOSSIL BROOK

LIX. MULLIGAN'S FIRST PALMER EXPEDITION, 1873, AND THE

DISCOVERY OF PAYABLE GOLD

LX. DALRYMPLE'S EXPEDITION, 1873—THE BEGINNINGS OF

COOKTOWN AND THE FIRST RUSH FROM COOKTOWN TO THE PALMER

LXI. MULLIGAN'S SECOND PALMER EXPEDITION, 1874—FROM

THE PALMER TO THE JUNCTION OF THE ST. GEORGE AND MITCHELL RIVERS, AND BACK

LXII. MULLIGAN'S THIRD EXPEDITION, 1874—FROM THE

PALMER TO THE WALSH

LXIII. MULLIGAN'S FOURTH EXPEDITION, 1874—ST. GEORGE

AND MCLEOD RIVERS AND THE HEADS OF THE NORMANBY AND PALMER

LXIV. MULLIGAN'S FIFTH EXPEDITION, 1875—COOKTOWN TO

JUNCTION CREEK

LXV. MULLIGAN'S FIFTH EXPEDITION, 1875, CONTINUED: JUNCTION

CREEK TO THE COLEMAN RIVER AND COOKTOWN—SIXTH EXPEDITION AND DISCOVERY OF

THE HODGKINSON GOLDFIELD

LXVI. THE COEN GOLDFIELD AND ITS PROSPECTORS, 1876-8

LXVII. THE AUTHOR'S EXPLORATIONS,

1879-80—INTRODUCTORY AND EXPLANATORY

LXVIII. THE AUTHOR'S EXPLORATIONS, 1879-80, CONTINUED:

FIRST EXPEDITION—COOKTOWN TO COEN DIGGINGS AND THE ARCHER RIVER, AND BACK

TO COOKTOWN, 1879

LXIX. THE AUTHOR'S EXPLORATIONS, 1879-80, CONTINUED: SECOND

EXPEDITION—WITH CROSBIE'S PROSPECTING PARTY—COOKTOWN TO THE ARCHER

RIVER

LXX. THE AUTHOR'S EXPLORATIONS, 1879-80, CONTINUED: SECOND

EXPEDITION, CONTINUED: WITH CROSBIE'S PROSPECTING PARTY—ACROSS THE

MCILWRAITH RANGE FROM THE ARCHER RIVER TO THE NISBET RIVER

LXXI. THE AUTHOR'S EXPLORATIONS, 1879-80, CONTINUED: SECOND

EXPEDITION, CONTINUED: WITH CROSBIE'S PROSPECTING PARTY—THE NISBET AND

LOCKHART RIVERS AND HAYS CREEK

LXXII. THE AUTHOR'S EXPLORATIONS, 1879-80, CONTINUED:

SECOND EXPEDITION, CONTINUED: WITH CROSBIE'S PROSPECTING PARTY—FROM THE

LOCKHART RIVER, ACROSS THE MCILWRAITH RANGE TO THE PASCOE RIVER

LXXIII. THE AUTHOR'S EXPLORATIONS, 1879-80, CONTINUED:

SECOND EXPEDITION, CONTINUED: WITH CROSBIE'S PROSPECTING PARTY—FROM THE

PASCOE RIVER TO TEMPLE BAY (OPPOSITE PIPER ISLAND LIGHTSHIP)

LXXIV. THE AUTHOR'S EXPLORATIONS, 1879-80, CONTINUED:

SECOND EXPEDITION, CONTINUED: WITH CROSBIE'S PROSPECTING PARTY—"FIRST

PRELIMINARY REPORT," A SUMMARY OF OPERATIONS BETWEEN COOKTOWN AND TEMPLE

BAY

LXXV. THE AUTHOR'S EXPLORATIONS, 1879-80, CONTINUED: SECOND

EXPEDITION, CONTINUED: WITH CROSBIE'S PROSPECTING PARTY—FROM TEMPLE BAY,

THROUGH THE "BAD LANDS" OR "WET DESERT," TO THE HEAD OF THE JARDINE RIVER

LXXVI. THE AUTHOR'S EXPLORATIONS, 1879-80, CONTINUED:

SECOND EXPEDITION, CONTINUED: WITH CROSBIE'S PROSPECTING PARTY—FROM THE

HEAD OF THE JARDINE RIVER, BY THE PACIFIC COAST, TO FALSE ORFORD NESS

LXXVII THE AUTHOR'S EXPLORATIONS, 1879-80, CONTINUED:

SECOND EXPEDITION, CONTINUED: WITH CROSBIE'S PROSPECTING PARTY—"SECOND

PRELIMINARY REPORT," A SUMMARY OF EVENTS FROM TEMPLE BAY TO FALSE ORFORD

NESS

LXXVIII. THE AUTHOR'S EXPLORATIONS, 1879-80, CONTINUED:

WITH CROSBIE'S PROSPECTING PARTY—FROM FALSE ORFORD NESS TO SOMERSET

LXXIX. THE AUTHOR'S EXPLORATIONS, 1879-80, CONTINUED: WITH

CROSBIE'S PROSPECTING PARTY—"THIRD PRELIMINARY REPORT," A SUMMARY OF

EVENTS FROM FALSE ORFORD NESS TO SOMERSET

LXXX. THE AUTHOR'S EXPLORATIONS, 1879-80, CONTINUED: AN

AFTERWORD

LXXXI. DONALD LAING—A PROSPECTING EXPEDITION IN THE

MCILWRAITH RANGE, 1879-80

LXXXII. J. T. EMBLEY'S EXPLORATIONS AND SURVEYS—I.

EXPEDITION FROM THE HANN RIVER TO THE GULF AND BACK TO THE (SOUTH) COEN,

1884

LXXXIII. J. T. EMBLEY'S EXPLORATIONS AND SURVEYS,

CONTINUED: II. THE PRINCESS CHARLOTTE BAY RIVERS, ETC., 1883-5

LXXXIV. J. T. EMBLEY'S EXPLORATIONS AND SURVEYS,

COTITINUED: III. EAST COAST RIVERS NORTH OF THE ROCKY RIVER GOLDFIELD

LXXXV. J. T. EMBLEY'S EXPLORATIONS AND SURVEYS, CONTINUED:

IV. THE WESTERN RIVERS OF THE PENINSULA

LXXXVI. J. T. EMBLEY'S EXPLORATIONS AND SURVEYS, CONTINUED:

V. THE SOUTHERN GULF RIVERS

LXXXVII. J. T. EMBLEY'S EXPLORATIONS AND SURVEYS,

CONTINUED: VI. THE CAPE YORK DISTRICT

LXXXVIII. THE CAPE YORK TELEGRAPH LINE,

1883-7—BRADFORD'S PRELIMINARY EXPLORATION—SURVEYS DURING

CONSTRUCTION

LXXXIX. MISSIONARY EXPLORATIONS

XC. MINUTIAE OF MARINE SURVEYS —H. M. S. "PALUMA,"

1890-4

XCI. MINUTIAE OF MARINE SURVEYS, CONTINUED: H.M.S. "PALUMA"

AND THE JANET RANGE, 1890-3

XCII. MINUTIAE OF MARINE SURVEYS, CONTINUED: H.M.S. "DART"

AND THE MACROSSAN RANGE, 1896-8

XCIII. WILLIAM BAIRD, 1887-96

XCIV. JOHN DICKIE, 1887-1920

XCV. DICKIE, DICK AND SHEFFIELD IN THE MCILWRAITH AND

MACROSSAN RANGES, 1910

XCVI. WILLIAM LAKELAND, 1876-1910

XCVII. WILLIAM BOWDEN, 1892-1901

XCVIII. ABORIGINAL PROSPECTING—PLUTO AND THE BATAVIA

RIVER, 1910-16

XCIX. CONCLUSION

INDEX OF PERSONS

INDEX OF LOCALITIES

INDEX OF SUBJECTS

R. LOGAN JACK, 1920

Photo. Johnson Sydney.

ABEL JANSZOON TASMAN, 1664 [1]

Reproduced from Jose's History of Australasia.

[1) In this case, and some others, the date of the portrait is conjectural.]

JAMES COOK, 1772

Reproduced from Glasgow Issue of Cook's Voyages, 1807.

WILLIAM BLIGH, 1812

Reproduced from Jose's History.

MATTHEW FLINDERS, 1811

Reproduced from Scott's Life of Flinders.

PHILLIP PARKER KING

Reproduced from Feldheim's Brisbane Old and New.

J. BEETE JUKES, 1870

Photo, from Bust by Joseph Watkins, R.H.A.

LUDWIG LEICHHARDT, 1844

Reproduced from Long's Stories of Australian Exploration.

EDMUND BESLEY COURT KENNEDY, 1847

Reproduced from Long's Stories of Australian Exploration.

WILLIAM CARRON, 1870

Reproduced from Journ. Roy. Soc., N.S.W., Vol. 42.

SIR AUGUSTUS CHARLES GREGORY, 1898

Photo, lent by Hugh Macintosh, Brisbane.

ROBERT O'HARA BURKE, 1860

Reproduced from Long's Stories of Australian Exploration.

WILLIAM JOHN WILLS, 1860

Reproduced from Long's Stories of Australian Exploration.

WILLIAM LANDSBOROUGH, 1870

Reproduced from Feldheim's Brisbane Old and New.

JOHN McKINLAY, 1870

Reproduced from Feldheim's Adelaide Old and New.

FRANK (LEFT) AND ALICK JARDINE (RIGHT), 1867

Reproduced from Byerley's Jardine Expedition.

FRANK JARDINE, 1917

Reproduced from Queenslander of 10th November, 1917.

RICHARD DAINTREE, 1871

Reproduced from Dunn's Founders of the Geological Survey of

Victoria.

WILLIAM HANN, 1873

Reproduced from Photo, lent by his daughter Mrs. Charles Clarke, Maryvale.

NORMAN TAYLOR, 1873

Reproduced from Dunn's Founders of the Geological Survey of

Victoria.

THOMAS TATE, 25 JUNE, 1913 (71st BIRTHDAY)

Reproduced from Photo, lent by his daughter Mrs. Leake, Maxwellton,

Queensland.

HANN EXPEDITION, 1872: (LEFT) THOMAS TATE; (LEANING)

WILLIAM HANN; (ERECT) FRED WARNER; NORMAN TAYLOR (RIGHT)

Reproduced from Photo, lent by Mrs. Leake.

GEORGE ELPHINSTONE DALRYMPLE, 1876

Reproduced from Feldheim's Brisbane Old and New.

WILLIAM J. WEBB, 1916

Reproduced from Photo, lent by himself.

JOHN MOFFAT, 1904

Reproduced from Photo, lent by his daughter Miss E. L. Moffat.

JAMES VENTURE MULLIGAN, 1905

Photo. Poulsen, Brisbane, lent by T. J. Byers, Hughenden.

ROBERT LOGAN JACK, 1877

Photo. McKenzie, Paisley.

BENJAMIN NEAVE PEACH, 1877

Photo. Bowman, Glasgow.

JAMES CROSBIE, 1891

Reproduced from Photo, lent by Mrs. Crosbie.

JAMES SIMPSON LOVE, 1878

Photo. Munro, Edinburgh.

JAMES SIMPSON LOVE, 1920

Photo. Bernice Agar, Sydney.

SIR THOMAS MCILWRAITH, 1893

Photo, lent by Hugh Macintosh, Brisbane.

HUGH LOCKHART, 1875

Photo. Moffat, Edinburgh.

EDWARD HULL, 1869

Photo. A. G. Tod, Cheltenham.

JANET SIMPSON JACK, 1920

Photo. Bernice Agar, Sydney.

JOHN T. EMBLEY, 1887

Photo. Turtle & Co.

JOHN T. EMBLEV, 1919

Photo. J. Ward Symons.

JOHN DICKIE, 1912

Reproduced from Photo, lent by W. J. Webb.

JAMES DICK, 1910

Reproduced from Photo, lent by W. J. Webb.

A. CAPE YORK TO NEW GUINEA = QUEENSLAND 4-MILE MAP, SHEET 21B, WITH ADDITIONS FROM ADMIRALTY CHARTS. SHOWS SEA ROUTES OF "SAN PEDRO" (TORRES), 1606; "DUYFKEN" (JANSZOON), 1606; "PERA" (CARSTENSZOON AND SLUIJS) AND "AERNEM" (VON COOLSTEERDT), 1623; "LIMMEN" (TASMAN), 1643; "RIJDER" (GONZAL), 1756; "BUIJS" (ASSCHENS), 1756; "ENDEAVOUR" (COOK), 1770; "BOUNTY'S" LAUNCH (BLIGH), 1789; "PANDORA" AND HER BOATS (EDWARDS), 1791; "PROVIDENCE" (BLIGH) AND "ASSISTANT" (PORTLOCK), 1792; "HORMUZEER" (BAMPTON) AND "CHESTERFIELD" (ALT), 1793 "INVESTIGATOR" (FLINDERS), 1802; "CUMBERLAND" (FLINDERS), 1803; "MERMAID" (KING), 1818; "ISABELLA" (LEWIS), 1836; "TIGRIS" (IGGLESTON), 1836; "ASTROLABE" AND "MEE" (DUMONT-D'URVILLE), 1840; "FLY" (BLACKWOOD), "BRAMBLE" (YULE) AND "PRINCE GEORGE," 1843-5; "RATTLESNAKE" (STANLEY), 1849 "BASILISK" (MORESBY), 1871-3: AND LAND ROUTES OF KENNEDY AND JACKEY-JACKEY, 1848; F. AND A. JARDINE, 1865; JACK, 1880; BRADFORD, 1883.

B. ORFORD NESS TO CAPE WEYMOUTH AND VRILYA POINT TO ALBATROSS BAY = QUEENSLAND 4-MILE MAP, SHEET 21A, WITH ADDITIONS FROM ADMIRALTY CHARTS. SHOWS SEA ROUTES OF "DUYFKEN," 1606; "PERA" AND "AERNEM," 1623; "LIMMEN," 1644; "BUIJS," 1756; "RIJDER," 1756; "ENDEAVOUR," 1770; "BOUNTY'S" LAUNCH, 1789; "INVESTIGATOR," 1802; "FLY," "BRAMBLE" AND "MIDGE," 1843; "RATTLESNAKE" AND "BRAMBLE," 1848; "ARIEL" (DOBSON), 1848; "FREAK" (SIMPSON) AND HER WHALEBOAT, 1849: AND LAND ROUTES OF KENNEDY, 1848; F. & A. JARDINE, 1865; JACK, 1880; PENNEFATHER, 1881; BRADFORD, 1883; HEY, 1895; EMBLEY, 1897.

C. LLOYD BAY TO STEWART RIVER = PARTS OF QUEENSLAND 4-MILE MAPS 20C AND 20D, WITH ADDITIONS FROM ADMIRALTY CHART. SHOWS SEA ROUTES OF "ENDEAVOUR," 1770; "BOUNTY'S" LAUNCH, 1789; "BRAMBLE" (YULE), 1843; "RATTLESNAKE" AND "BRAMBLE," 1848; "DART," 1896-8: AND LAND ROUTES OF KENNEDY, 1848; W. HANN, 1872; JACK, 1879-80; BRADFORD, 1883; EMBLEY, 1884-96; DICKIE, 1901; DICKIE, DICK AND SHEFFIELD, 1910.

D. ALBATROSS BAY TO CAPE KEERWEER, GULF OF CARPENTARIA = PART OF QUEENSLAND 4-MILE MAP, SHEET 20D, WITH ADDITIONS FROM ADMIRALTY CHART. SHOWS SEA ROUTES OF "DUYFKEN," 1606; "PERA" AND "AERNEM," 1623; "LIMMEN" (TASMAN), 1644; "BUIJS," 1756; "RIJDER," 1756; "INVESTIGATOR" (FLINDERS), 1802: AND LAND ROUTES OF F. AND A. JARDINE, 1864-5; EMBLEY, 1884-95; HEY, 1892-1919; MESTON, 1896; JACKSON, 1902.

E. COOKTOWN TO PRINCESS CHARLOTTE BAY = QUEENSLAND 4-MILE MAP, SHEET 20A, WITH ADDITIONS FROM ADMIRALTY CHARTS. SHOWS SEA ROUTES OF "ENDEAVOUR" (COOK), 1770; "MERMAID" (KING), 1819; "BATHURST" (KING), 1821; "FLY" (BLACKWOOD) AND "BRAMBLE" (YULE), 1843; "RATTLESNAKE" (STANLEY) AND "BRAMBLE" (YULE), 1848; AND LAND ROUTES OF KENNEDY, 1848; HANN, 1872; MULLIGAN, 1875; JACK, 1879; BRADFORD, 1883; EMBLEY, 1884.

F. HAMILTON AND PHILP GOLDFIELDS AND WESTWARD TO THE GULF OF CARPENTARIA, WITH THE KENDALL, HOLROYD, EDWARD, COLEMAN AND MITCHELL RIVERS = QUEENSLAND 4-MILE MAP, SHEET 20B, WITH ADDITIONS FROM ADMIRALTY CHART. SHOWS SEA ROUTES OF "PERA" AND "AERNEM," 1623; "LIMMEN" (TASMAN), 1644; "INVESTIGATOR" (FLINDERS), 1802: AND LAND ROUTES OF F. AND A. JARDINE, 1864; HANN, 1872; MULLIGAN, 1875-95; JACK, 1879-80; EMBLEY, 1874-1896; BRADFORD, 1883; DICKIE, 1901.

G. CAPE GRAFTON TO WEARY BAY AND CAIRNS TO PALMER RIVER = QUEENSLAND 4-MILE MAP 18C AND PART OF 18D, WITH ADDITIONS FROM ADMIRALTY CHART. SHOWS SEA ROUTE OF "ENDEAVOUR" (COOK), 1770: AND LAND ROUTES OF LEICHHARDT, 1845; KENNEDY, 1848; HANN, 1872; MULLIGAN, 1873-75; DICKIE, 1901.

H. PALMER, MITCHELL, LYND, STATEN AND GILBERT RIVERS, AND PART OF THE GULF OF CARPENTARIA = QUEENSLAND 4-MILE MAP, SHEET 18D AND PART OF 19C, WITH ADDITIONS FROM ADMIRALTY CHARTS. SHOWS SEA ROUTES OF "PERA" AND "AERNEM:, 1623; "LIMMEN" (TASMAN), 1644; "BEAGLE" (STOKES), 1841: AND LAND ROUTES OF LEICHHARDT, 1845; F. AND A. JARDINE, 1864; HANN, 1872; MULLIGAN, 1875; EMBLEY, 1884-7; DICKIE, 1891.

K. ETHERIDGE, CHILLAGOE, HERBERTON, CARDWELL AND THE HEADS OF THE HERBERT AND BURDEKIN RIVERS = QUEENSLAND 4-MILE MAP 18A, 2-MILE MAP OF COOK DISTRICT, SHEETS 5 AND 6, AND 2-MILE MAP OF KENNEDY DISTRICT, SHEET 9. SHOWS LAND ROUTES OF LEICHHARDT, 1845; KENNEDY, 1848; HANN, 1872; MULLIGAN, 1873-75.

L. CROYDON AND PART OF ETHERIDGE GOLDFIELDS, THE GILBERT, ETHERIDGE AND EINASLEIGH RIVERS AND THE HEAD OF THE SO-CALLED STAATEN RIVER = QUEENSLAND 4-MILE MAP, SHEET 18B. SHOWS LAND ROUTES OF GREGORY, 1856; MCKINLAY, 1862; F. AND A. JARDINE, 1864; MACDONALD, 1864.

M. BURKETOWN, NORMANTON AND THE SOUTHERN MOUTHS OF THE GILBERT RIVER = QUEENSLAND 4-MILE MAP, SHEET 19A, WITH ADDITIONS FROM ADMIRALTY CHARTS. SHOWS SEA ROUTES OF "PERU" AND "AERNEM," 1623; "LIMMEN" (TASMAN), 1644; "INVESTIGATOR" (FLINDERS), 1802; "BEAGLE" (STOKES) AND HER BOATS, 1841: AND LAND ROUTES OF LEICHHARDT, 1845; GREGORY, 1856; BURKE AND WILLS, 1861; WALKER, 1861; LANDSBOROUGH, 1862; MCKINLAY, 1862; MACDONALD, 1864.

N. NORTH WESTERN CORNER OF QUEENSLAND, AND THE GULF OF CARPENTARIA = QUEENSLAND 4-MILE MAP, SHEET 19A AND PART OF 19D, WITH ADDITIONS FROM ADMIRALTY CHARTS. SHOWS SEA ROUTES OF "LIMMEN" (TASMAN), 1644; "INVESTIGATOR" (FLINDERS), 1802; "BEAGLE'S" BOATS, 1841: AND LAND ROUTES OF LEICHHARDT, 1845; GREGORY, 1856; LANDSBOROUGH, 1861; BEDFORD, 1882; EMBLEY, 1889.

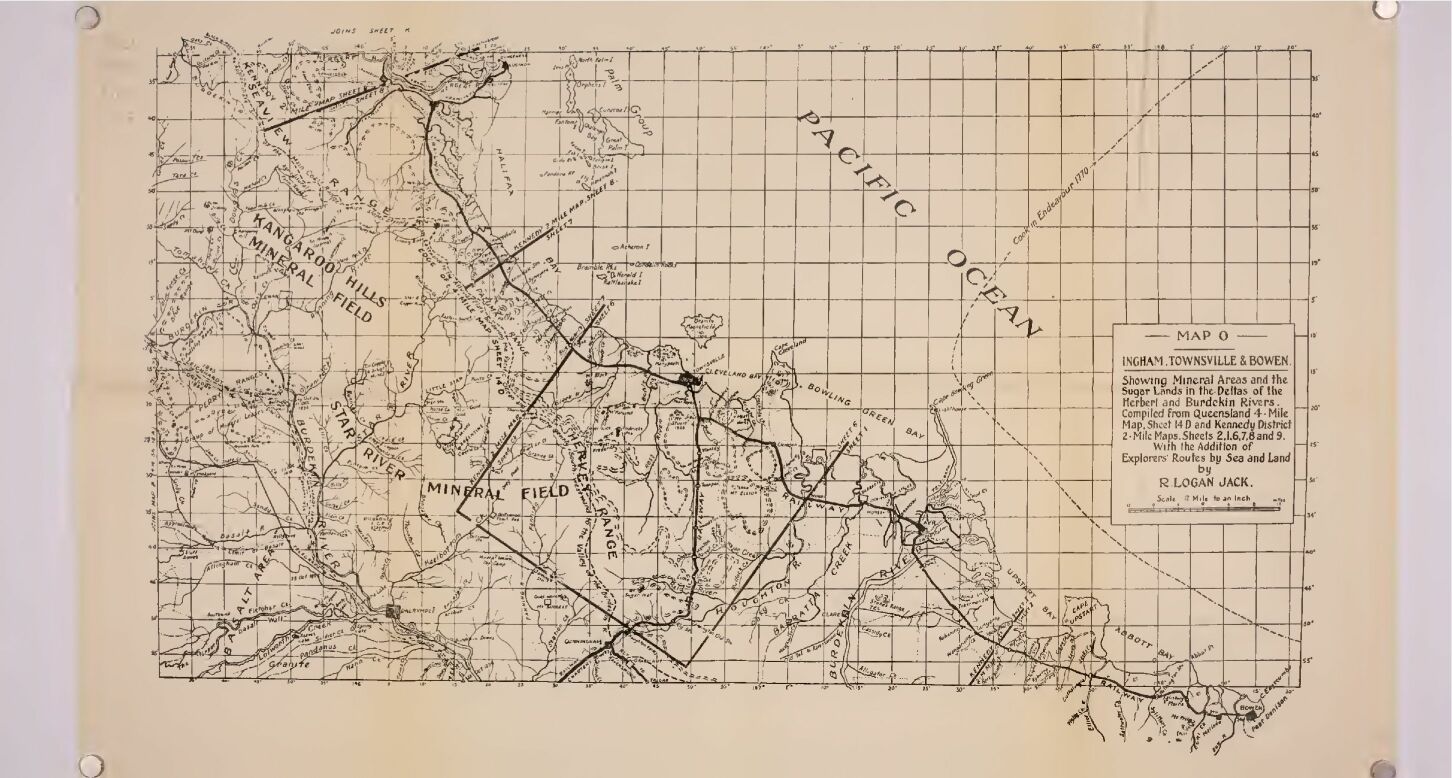

O. INGHAM, TOWNSVILLE AND BOWEN, AND DELTAS OF HERBERT AND BURDEKIN RIVERS = QUEENSLAND 4-MILE MAP, SHEET 14D AND KENNEDY DISTRICT 2-MILE MAP, SHEETS, 1, 2, 6, 7, 8 AND 9. SHOWS SEA ROUTE OF "ENDEAVOUR" (COOK), 1770: AND LAND ROUTES OF LEICHHARDT, 1845; GREGORY, 1856.

P. THE UPPER BURDEKIN VALLEY AND THE ETHERIDGE, GILBERT AND WOOLGAR GOLDFIELDS = QUEENSLAND 4-MILE MAP, SHEET 15C AND PART OF 15D. SHOWS LAND ROUTES OF LEICHHARDT, 1845; GREGORY, 1856; MCKINLAY, 1862; MACDONALD, 1864; DAINTREE, 1864-9.

Q. CARDWELL, TOWNSVILLE, BOWEN, WINTON, ETC., INCLUDING MAPS O AND P, PARTS OF K AND L, AND QUEENSLAND 4-MILE MAPS 14B, 15A, 10D, 11C, AND PARTS OF 14A, 15B, 15D, L0C AND 11D. SHOWS LAND ROUTES OF LEICHHARDT, 1845; KENNEDY, 1848; F. AND A. JARDINE, 1864; GREGORY, 1856; WALKER, 1861; MCKINLAY, 1862; WALKER, 1862; LANDSBOROUGH, 1862; MACDONALD, 1864; DAINTREE, 1863-70; WRIGLEY (AEROPLANE), 1919; ROSS-SMITH (AEROPLANE), 1919.

R. CAMOOWEAL, CROYDON, MOUNT CUTHBERT, CLONCURRY, SELWYN, COLLINGWOOD, INCLUDING PARTS OF L, M AND N, QUEENSLAND 4-MILE MAPS, SHEETS 16C, 16D, 16A, 16B, 12C AND 12D, AND PARTS OF 15D, 15C AND 11D. SHOWS LAND ROUTES OF LEICHHARDT, 1845; GREGORY, 1856; BURKE AND WILLS, 1861; WALKER, 1861; LANDSBOROUGH, 1862; MCKINLAY, 1862; MACDONALD, 1864; JACK, 1881; WRIGLEY (AEROPLANE), 1919; ROSS-SMITH (AEROPLANE), 1919.

The author desires specially to record his thanks to the undernoted persons and institutions. References to many others who assisted him will be found in the text.

AGAR, BERNICE, Sydney. For special pains in the production of photographs of R. Logan Jack, Janet Simpson Jack and James Simpson Love.

ANGUS & ROBERTSON, LTD., Sydney. For permission to produce portraits of Tasman, Bligh and Flinders from books published by them.

BRADFORD, JOHN R., Brisbane. For permission to publish his report (1883) on the Exploration preliminary to the construction of the Cape York Telegraph Line; for information which proved instrumental in tracing my lost maps; and for much useful information which is embodied in the text.

BRADY, A. B., Under Secretary for Works, Queensland. For copies of documents relating to Mulligan's explorations.

BYERS, T. J., Hughenden. For portrait of Mulligan and much information.

CLARK, MRS., Maryvale, Queensland. For portrait group of members of the expedition led by her father, William Hann; for Biographical Details re members of the expedition and Daintree and for other information.

CROSBIE, MRS. J. D., Cairns. For portrait of her late husband, James Crosbie, biographical notes and other information.

CULLEN, E. A., Harbours and Rivers Department, Brisbane. For information re Batavia River and Port Musgrave.

DICK, (THE LATE) James, Cooktown. For information re prospecting in Cape York Peninsula, communicated in correspondence from 1911 till his death in 1916. His many letters amounted almost to collaboration. Indirectly, as is explained in the introductory chapter, he may be said to have brought about the expansion of a proposed annotated version of my reports on the 1879-80 expeditions, on which I was engaged when the correspondence began, into a history covering three centuries of exploration.

DUNN, E. J., formerly Government Geologist of Victoria. For permission to reproduce portraits of Norman Taylor and Richard Daintree from his Founders of the Geological Survey of Victoria.

DUNSTAN, B., Government Geologist, Queensland. For a search in his office for copies of my lost maps; and for the loan of official documents left by me.

EMBLEY, J. T., Melbourne. For portraits of himself; for a special article on his expedition (1884) with Clark, and for information re the McIlwraith and Macrossan Ranges, the Western Rivers, the discovery and occupation of pastoral country in the north, etc. The assistance rendered by him in some portions of this work amounted to collaboration.

FOOT, MRS. W., Cardington, Queensland. For portrait of her father, William Hann, and for information re the Hann expedition, the Etheridge and Gilbert Rivers, etc.

GREEN, D., Townsville. For many contributions of newspaper articles re northern explorers and pioneers, and for gratuitous advertisements in the newspapers controlled by him with the object of eliciting information required by me.

HEERES, J. E., LL.D., formerly Professor at the Dutch Colonial Institute, Delft, afterwards at the University of Leiden. For permission to quote from the English translation of his exhaustive work on The Part borne by the Dutch in the Discovery of Australia, 1606-1765, and to his publishers, "The Late E. J. Brill Company, Limited," Leiden, for their consent.

HEY, REV. NICHOLAS, late of the Mapoon Aboriginal Mission. For geographical and ethnological notes; for notes on explorations by the missionaries, and especially for assisting in the identification of what I believe to be "Coen Revier" of the "Pera" and "Aernem" Expedition.

JOHNSON, L., Sydney. For special care in the reproduction of old portraits from originals in some instance faded or damaged.

JONES, REV. JOHN, Church of England Board of Missions, Sydney. For information re Aborigines of the Mitchell Delta, etc.

LEAKE, MRS., Merriula, Maxwellton, Queensland. For portrait of her father, Thomas Tate; for documents relating to the wreck of the "Maria" in which he took part, and for other information.

LEES, WILLIAM, Brisbane. For assistance and encouragement in my work. For several years back he continually contributed any writing which came under his observation as a journalist, and which appeared to bear on the subject of my study. His extensive knowledge of the North of Queensland and his wide reading enabled him to amass knowledge most useful to me.

LOVE, JAMES SIMPSON, Townsville. For information regarding recent developments in North Queensland. He was the youngest member of my Second Expedition (1879-80), and has since been in a position to acquire a very intimate knowledge of the Cape York Peninsula.

MACGREGOR, THE LATE SIR WILLIAM, G.C.M.G., etc. Administrator and Lieutenant Governor of British New Guinea, Governor of Lagos, Governor of Newfoundland and Governor of Queensland. But for his death (on 4th July, 1919) this book would have been dedicated to him in grateful recognition of his services to science and of his personal and stimulating interest in my geographical and geological work and in the historical questions which I had under investigation. He wrote me on 29th December, 1916: "I am glad to learn that you have on the stocks a work of the kind you mention. I should indeed consider it a very real honour to have it dedicated to me, for I know well that it would be the standard of reference for future generations when personally we are long off the scene."

MACINTOSH, HUGH, Brisbane. For portraits of Sir Augustus Gregory and Sir Thomas McIlwraith, and for a mass of information re explorations, surveys, dates, names, etc., in answer to my inquiries extending over the last decade. His long experience in the Survey Office made him an unrivalled authority on such matters.

McLAREN, JOHN, Utingu, near Cape York. For information re the Coco-nut plantation and conditions in the Cape York district generally.

MAIDEN, J. H., C.M.G., Government Botanist, Sydney. For permission to reproduce portrait of William Carron from his Records of Australian Botanists, and for botanical notes.

MARSHALL, HENRY, Under Secretary for Mines, Brisbane. For the text of James Dick's report on the Dickie, Dick and Sheffield traverse of the McIlwraith Range; for a search in the archives of the Department for my missing map; for statistical and other information.

MITCHELL LIBRARY, Sydney, and HUGH WRIGHT, Librarian. For access to books and maps and special facilities for the examination of Kennedy and early Dutch-Australian Literature and documents.

MOFFAT, Miss E. L., Sydney. For portrait of her father, the late John Moffat.

PARLIAMENTARY LIBRARY, BRISBANE, and J. MURRAY, Librarian. For official statement re construction of Cape York Telegraph.

PARLIAMENTARY LIBRARY, SYDNEY, and F. WALSH, Librarian. For access to Books, Newspaper files and documents and facilities for the perusal of Kennedy and other documents.

PATERSON, FRANK J., TOOWOOMBA, Queensland. For information which assisted in tracing my lost maps and for reminiscences of the survey and construction of the Cape York Telegraph.

POSTMASTER GENERAL'S DEPARTMENT (Federal) and J. McCoNAcniE, Deputy P.M.G., Queensland. For copy of Bradford's report on Cape York Telegraph Survey (1883-4), with maps, and for permission to publish.

PUBLIC LIBRARY, SYDNEY, and W. H. IFOULD, Librarian. For access to Parliamentary papers and documents.

PUBLIC LIBRARY, MELBOURNE. For access to books and maps.

QUEENSLANDER NEWSPAPER, Brisbane. For permission to reproduce portrait of Frank Jardine.

SPOWERS, ALLAN A., Surveyor General, Queensland. For maps of the Department of Lands, and officially authenticated information re explorations and surveys.

WEBB, W. J., Cooktown. For special article on the Cooktown Palmer Rush (1873); for portraits of Dickie, Dick and himself; and for notes on early prospectors.

WHITCOMBE AND TOMBS, Melbourne. For permission to reproduce portraits of Leichhardt, Kennedy, Burke and Wills from books published by them.

WHITE, C. T., Government Botanist, Queensland. For botanical notes, and especially for notes and references re Gastrolobium.

{Page 1}

The Cape York Peninsula, forming, as it does, the link binding the two great islands of Australia and New Guinea, is necessarily of the highest importance from a geological, ethnological, zoological, botanical, historical, political and strategical point of view.

It so happens that the Peninsula is the first part of Australia to which authentic written history refers. On the earliest landing of Europeans there arose the complex questions which obtrude themselves whenever civilisation comes into contact with barbarism.

My practical interest in the Peninsula began with a tour made in 1879 in the course of my Geological Survey work. On my way to the recently rushed and still more recently abandoned "Coen" gold diggings, I crossed the base of the then almost unknown Cape Melville Peninsula, where I found indications of auriferous country, and also the rivers south of Princess Charlotte Bay, down which the unfortunate explorer Kennedy had struggled in vain to keep his appointment with the relief ship twenty-two years earlier. From the Coen, I was only able to push out to the north for a period inexorably limited by the condition of my horses and the quantity of food remaining in my saddle-bags. Even under these conditions, however, I penetrated for some distance into the McIlwraith Range, and on the heads of the river which I named the Peach (unaware that it was the river named the Archer by the Brothers Jardine, who crossed it near its mouth) I found widespread evidence of the presence of gold and tin.

From the Laura Telegraph Office, from Cooktown, and ultimately from my headquarters at Townsville, I made such communications as were possible in anticipation of a complete report to the head of the Department of Mines, which administered the Geological Survey.

My individual impression was that the reefs in the district traversed were of more importance than the alluvial gold, but there had been neither means nor time at my disposal to enable me to satisfy myself of the value of either, and this view I duly represented in my correspondence with the Department.

{Page 2}

The desire of the Government, and of the eager diggers throughout Queensland, was to discover an alluvial goldfield on the pattern of the Palmer, which was by that time approaching exhaustion.

A party of miners, headed by James Crosbie, volunteered to go and settle the question of the existence of payable alluvial gold, and they asked for and obtained government assistance, and I was instructed to lead them to the spot. In addition, a prospecting party was equipped, with money subscribed in Cook-town, and sent out to anticipate the expedition subsidised by the Government.

The combined geological and prospecting parties left Cooktown on 26th November, 1879, and striking out from the "bend of the Kennedy" on the Cooktown-Palmerville road, reached the "Peach" (Archer) River on 20th December. The prospectors commenced operations at once, and were rewarded with "prospects" which led them into the jungle-clad recesses of the McIlwraith Range. Here, to their disappointment, although prospects were obtained here and there, the creeks and gullies were found to run over almost bare rocks, their beds being too steep for the retention of any quantity of alluvial "washdirt." On 30th December, the wet season set in. For the remainder of our time in the field, the creeks were too swollen for the "bottom" to be reached where there was any washdirt at all, or the ground was too sodden to carry our horses. There were long and vexatious delays when it was neither possible to work nor to travel. Nevertheless, we continued, during breaks in the bad weather, to cross the McIlwraith Range and touch the Macrossan Range. Regaining the summit of the McIlwraith Range, we followed it to its northern extremity, where the valley of the Pascoe River separates it from the mountain mass which we named the Janet Range. It was found that the Pascoe River bounds the Janet Range on the south and east, and we practically followed it down till we had finally to cross it where it took an easterly course towards the Pacific. We had already made up our minds that it was safer to chance the unknown in the north than to return to Cooktown across several great rivers, now all certain to be flooded. No sooner had we left the Pascoe than we entered on the Bad Lands or Wet Desert of "heath" and "scrub" without anything for horses to live on. From the Pascoe to the Escape River, our course must have coincided in many places with Kennedy's on his "forlorn hope" journey, and we repeated many of his experiences, as told by his surviving companion Jackey-Jackey, but happily not the series of disasters which resulted in his own death and the disasters which overtook the two parties he left behind to await the relief he went to bring. The natives displayed in our case, as in Kennedy's, a persistent hostility which hampered our

{Page 3}

movements and partially incapacitated me during the final stages of the journey. Horses died of starvation or poison, and the men of the party were running perilously short of food—the journey having been prolonged beyond our calculations—when we reached Somerset on 3rd April, 1880.

Kennedy's maps and journals (1848) perished with him, and what we know of his expedition is taken (as far north as the Pascoe River) from the narrative written by William Carron, one of the three survivors, and (north of the Pascoe) from the "statement" of the black boy Jackey-Jackey, another of the survivors and the only one of the thirteen men to make the complete journey from Rockingham Bay to Somerset. The Geological and Prospecting Party's route only coincided for a short distance, from the head of the Jardine River to its westward bend, with that of the Jardine Brothers (1865). Day after day, during the whole of my journey, I was mapping the mountain ranges, rivers and other features of the country, checking my latitudes by star-observations whenever the night sky was clear enough, and as far as charting was concerned we were in virgin ground.

My report on the two expeditions was completed at my Townsville office in the winter of 1880 and sent to the Minister for Mines, Brisbane, with the relative map, which had taken a good deal of time, subject to interruptions by other duties. The report was printed and officially issued on 14th September, 1881, without my having had any opportunity of seeing it through the press, and to my astonishment the map—which might have been supposed to be of the first importance—was omitted. What became of the map and of my office copy will be seen in Chapter LXVII.

After the map had reached Brisbane and before my report was published, my map had been reduced to a smaller scale and embodied in official maps issued by the Department of Lands. In that form, however, my charting was open, in parts, to an interpretation which I could never have sanctioned.

In 1913, when.I had been out of the government service for about fourteen years, and when for the first time some degree of leisure had begun to fall to my share, I commenced to prepare a revised and corrected issue of the report, with its map reconstructed from my notes, with the intention of offering it to the Government for republication (the report itself having been long out of print). Some progress had been made when my friend James Dick, of Cooktown, sent me proofs of a pamphlet in which he proposed to summarise the narrative of the Geological and Prospecting Expeditions. When I had gone over the proofs, correcting them only in so far as statements of fact were concerned, I fully realised how misleading my original narrative must have been, misprinted as it was, and unaccompanied by the map which

{Page 4}

formed its most essential part. I resumed my task with renewed vigour, and with a wider scope, and Mr. Dick, up to the date of his death, assisted me in many ways through his local and personal knowledge, happily of more recent date than mine. I am grateful to his memory, and am conscious that he was, in a sense, "the only begetter of these ensuing lines."

Between 1880 and 1913, a great deal of charting of the interior had been accomplished by the Departments of Lands and Mines, although even now that work is incomplete. The new lines gave me, when I was recharting the lost map, an opportunity of correcting my sketching to correspond with actual surveys.

The first lesson to force itself upon me was that my estimates of distances covered had been influenced by fatigue or difficulties on the one hand (leading to over-estimation) or by good-going and good-feeding for the horses on the other (leading to underestimation).

The second lesson was that, even in the direction of my course, I had in many instances strayed to the right or left, as a ship may steer a definite course and yet make leeway owing to the pressure of forces incorrectly estimated, or even not recognised. In short, the personal equation had to be introduced and allowed for before I could hope to reconcile my supposed with my actual position on any given date.

Long before I had finished the revision of my own narrative, it had become evident that its significance could not be fully understood without a critical study of the diaries of explorers who had gone before me and whose paths I had crossed from time to time. This led me back from Mulligan to Leichhardt, and as one by one the writings of honoured pioneers came under my review, I subjected them to the tests already applied to my own, and to the best of my ability substituted where the writers were for where they thought they were, and made the necessary allowances and corrections. Then it seemed that the story might as well be continued to the present date by the addition of the developments which have taken place since 1880 through the instrumentality of surveyors, explorers and prospectors. Some of the actors are, happily, still alive, and these have rendered material assistance by the contribution of original matter. Among these are Webb, Bradford, Paterson and Embley. To the last-named gentleman, especially, I am indebted for assistance rendered doubly valuable by his prolonged residence in the Peninsula, and which, in some parts of the work, almost amounted to collaboration.

While dealing with land explorers it was borne in upon me that they owed some of their difficulties and many of their errors to an imperfect comprehension of the work of earlier maritime explorers. They were not, indeed, to be blamed for this, as in few instances could they have perused the narratives or seen the

{Page 5}

charts of the sea-adventurers. As it was, the Dutch sailors named "reviers," or inlets, on the Gulf coast, and subsequent explorers of the interior, almost without exception, made bad guesses at the connection of their rivers with the inlets on the coast line. I do not propose any reform so drastic as to restore their original names to the western rivers of the Peninsula, but content myself, after years of research, with distinguishing the original, or right, or de jure names from the de facto names, the product of pardonable misidentifications sanctioned, in many cases, by half a century of popular and official usage. I have, I hope, succeeded in making it clear that, in many instances, the de facto names are in reality not those bestowed by the earliest explorers, but rather what are called "complimentary" names.

From the preceding explanation, it will be understood that this work began, so to speak, in the middle, and followed lines dictated by the questions which arose during its progress. It was ultimately realised that it would be advisable to arrange it in chronological order, so that the tale told by each explorer might be compared with the facts ascertained by his predecessors and at the same time be complete in itself. Of no less importance was the consideration of precisely how much knowledge each explorer had of the achievements of his predecessors; and this point has exacted very careful study. I am forced to the conclusion that in most instances the later explorers knew very little about their predecessors, having taken what little they knew at second hand and without having had access to important documents, some of which, indeed, only came to light after their own time.

While aiming at chronological order, it must be conceded that it is not always possible to observe it strictly. It may be that the stories of two observers overlap; or a statement may demand historical investigation into the past; or, again, it may be convenient at once to trace the outcome of a newly discovered fact downwards to the present time. Hence a certain amount of repetition is inevitable, as facts or statements are viewed by one observer after another from a different angle.

It is impossible to define the exact base of the Cape York Peninsula, and in writing of it one must occasionally follow its pioneers beyond its southern boundary, however liberal or elastic the definition of the latter may be. The historian of France needs no excuse for referring to happenings in Germany or Italy. In a parallel way, what was commenced as a history of the Cape York Peninsula has come to include Torres Strait, the "Gulf" country west to the boundary of Queensland and the Pacific country as far south as Bowen.

SYDNEY,

30th September, 1920.

{Page 6}

SIXTEENTH- AND SEVENTEENTH-CENTURY IDEAS OF THE GREAT SOUTH LAND. WAS NEW GUINEA PART OF IT? SPANISH AND PORTUGUESE KNOWLEDGE. THE DAUPHIN CHART. DUTCH IDEAS. BULL OF POPE ALEXANDER VI. THE SPANISH MAIN. ENGLAND AND HOLLAND IN THE FIELD. MAGELHAEN'S VOYAGE TO THE PHILIPPINES. HIS DEATH. DID HIS OFFICERS TOUCH AUSTRALIA I QUIROS DISCOVERS SANTA CRUZ AND TRIES TO ESTABLISH A COLONY. WYTFLIET'S BELIEF THAT NEW GUINEA WAS DISTINCT FROM THE GREAT SOUTH LAND. SPANISH KNOWLEDGE OF THE STRAIT. QUIROS' NEW EXPEDITION. FLAGSHIP AND CONSORTS SEPARATE AT ESPIRITU SANTO (NEW HEBRIDES). QUIROS TAKES THAT ISLAND TO BE PART OF THE SOUTH LAND. TORRES DISPROVES THIS. LAYING-OUT THE NEW JERUSALEM. TORRES' REPORT DISCOVERED IN 1762. QUIROS' REPORT DISCOVERED IN 1876. TORRES' VOYAGE. STRIKES THE SOUTH SIDE OF NEW GUINEA. CLEARS TORRES STRAIT, PROBABLY BY THE BLIGH CHANNEL, ABOUT 24TH SEPTEMBER, 1606. DOES NOT CLAIM THE STRAIT AS HIS OWN DISCOVERY AND PROBABLY MADE FOR IT ON INFORMATION ALREADY IN HIS POSSESSION. REACHES THE MOLUCCAS ABOUT 28TH NOVEMBER, 1606. SUCCESSFULLY CONDUCTS LITTLE WAR AT TERNATE. REACHES THE PHILIPPINES ABOUT 12TH MAY, 1607.

A mass of vague and fragmentary evidence points to the conclusion that by the middle of the sixteenth century Spanish and Portuguese navigators had become aware that New Guinea was separated by a strait from a continent lying to the south. The knowledge was, however, jealously guarded. A significant passage occurs in an English edition, published in Louvain in 1597, of CORNELIS WYTFLIET'S Descriptionis Ptolemicae Augmentum (1597):

"The Australis Terra is the most southern of all lands. It is separated from New Guinea by a narrow strait. Its shores are hitherto but little known, since, after one voyage and another, that route has been deserted, and seldom is the country visited, unless when sailors are driven there by storms. The Australis Terra begins at two or three degrees from the equator, and is maintained by some to be of so great an extent that, if it were thoroughly explored, it would be regarded as a fifth part of the world." [1]

The inference, as pointed out by Collingridge, is inevitable that Wytfliet referred to sources of information other than Dutch.

Collingridge adduces [2] reasonable support for his contention that the western coast of Australia had been "charted". (although the word "sketched" might be more appropriate) by the Portuguese

[1) Collingridge, Discovery of Australia, p. 219.]

[2) British Association for the Advancement of Science: Sydney meeting, 1914. See also his work, The Discovery of Australia, Sydney, 1895, p. 172, where the "Dauphin Chart," dated 1530-1536, is reproduced.]

{Page 7}

and the eastern coast by the Spanish prior to the year 1530. In the DAUPHIN CHART, on which this conjecture is founded, the point identified as Cape York is, however, not depicted, as it really is, south of New Guinea, but as lying west of Timor and in the latitude of the north coast of Java. The supposed Gulf of Carpentaria has for its western limit the eastern end of Java, and from its south-western corner what may be called a strait or channel, or still more correctly a canal, runs westward between "Jave" on the north and "Jave la Grande," or Australia, on the south. The supposed Gulf of Carpentaria is, according to the map, interrupted by a few islands, and on it is written, in the Portuguese language, the legend "Anda ne Barcha" (no ships come here).[1] Collingridge conjectures that the French compiler of the map, ignorant of Portuguese, copied this legend from an older Portuguese map, under the impression that it was the name of the Gulf or of the group of islands.

In the sixteenth century, the islands between Asia and Australia came to be well known to European adventurers. In 1512, Portugal took possession of the Molucca group, the centre of the "Spice Islands," and this possession speedily grew to great commercial importance and passed into the hands of Spain. Magelhaen "discovered" the Philippines in 1520 and Spain annexed them fifty years later. Meantime the Dutch and the English were on the alert and looking for a foothold.

As far back as July, 1493, a BULL OF POPE ALEXANDER VI had fixed a north and south line of demarcation between the claims of Portugal and Spain to future discoveries. Portugal was to occupy the hemisphere to the east and Spain the hemisphere to the west of that line, which was placed 100 leagues (5° 43')[2] west of the Azores and Cape Verde Islands. The generosity of the Pope was no doubt fully appreciated by the two beneficiaries, but the line was not quite satisfactory to either of them; besides, it was ill-defined, because some six degrees of longitude extend between the westmost Azores and the eastmost Cape Verdes. A private arrangement or treaty was therefore made on 4th June, 1494, by Don Juan II of Portugal on the one hand and Isabella and Ferdinand of Spain on the other, whereby it was agreed that the line should run 370 leagues (21° 9') west of the Cape Verde Islands.

Assuming 25° W. to be the mean longitude of the Azores and Cape Verde Islands, the bull of 1493 bisected the globe by the meridians of 40° 43' W. and 149° 17' E., the latter meridian giving to Portugal the islands of the Pacific west of the eastmost cape of New Guinea and to Spain all those east of that cape. The treaty

[1) The equivalent of the phrase in modern Spanish, viz. "Barcas no andan," differs so little from the Portuguese that some hesitation may be felt in settling the question on the sole evidence of language. Blank ignorance of Portuguese on the part of a French cartographer is rather a bold assumption. The most genuinely learned men of these days were to be found among the compilers of maps.]

[2) 17½ Spanish leagues= 1 geographical degree.]

{Page 8}

of 1494 cut through the globe by the meridians of 46° 9' W. and 133° 51' E.

It must be remembered that COLUMBUS had just discovered the West Indian Islands a year before the issue of the papal bull. The mainland of America was discovered in 1497 by SEBASTIAN CABOT, a Venetian in the service of Henry VII of England. Then the passage of the SPANISH MAIN, the sphere of influence granted to Spain, became, for Europe, a question of very practical politics, over which much blood was to be shed, as other nations claimed the freedom of the sea. It was not till 1588 that the question was settled by the decisive defeat of the Spanish armada by the English fleet.

Had the nations outside of Spain and Portugal admitted the validity of the bull, the greater part of Australia would have belonged to Portugal, and a slice of the eastern coast, covering Sydney, Brisbane and Rockhampton, would have been Spanish. By the treaty (which was a sort of reciprocal Monroe doctrine), the western half of Australia would have been Portuguese and the eastern half Spanish.

It is needless to say that no other maritime powers ever assented to the partition between Spain and Portugal of all lands to be discovered in the future. The title of the two Powers was soon to be disputed by the rising maritime nations England and Holland. Moreover, the definition of the treaty line in the Pacific raised, between Spain and Portugal themselves, questions which brought them to the verge of war.

Here,then,was an excellent reason why Spaniards and Portuguese should preserve secrecy or practise deceit regarding the location of discoveries in the vicinity of the boundary line, whether by bull or treaty. The interest of a Portuguese tempted him, sometimes beyond his strength, to place his discovery west, while a Spaniard was tempted to place his discovery east of the boundary line in the Pacific. Secret instructions must have been issued to navigators by the authorities of both countries, in consequence of which they would systematically misrepresent their longitudes, and the truth would be arrived at by the authorities on reading the reports and charts with the aid of a "key."

Granting that the "Dauphin Chart" was compiled in parts from Spanish or Portuguese originals and that the land shown to the south of Java really represents the northern portion of Australia, which was already, early in the sixteenth century, vaguely known to both Spanish and Portuguese, the westward-moving of the new continent was clearly in the interest of Portugal, and the warning or danger signal "ships do not (or cannot or must not) come here"—in other words, "not navigable"—was clearly a "bluff." It was, therefore, probably a Portuguese map which was drawn upon for the information given in the Dauphin chart.

{Page 9}

MAGELHAEN AND CANO

MAGELHAEN, a Portuguese who had taken service with Spain, set out with five vessels from Luzar on 10th September, 1519. After passing through the strait which now bears his name, he reached the Philippine Islands, where he was killed by the natives. Only one ship of his squadron returned to Europe, via the Cape of Good Hope, carrying eighteen persons, all very sick. This ship was the "Victoria," Captain Juan Sebastian del CANO. The "Victoria" sailed via the Moluccas to Timor. Thence she must have gone south-westward till "certain islands" were discovered under the tropic of Capricorn. As this land, according to Cano, was only 100 leagues (5° 43') from Timor, it is more likely to have been the continent of Australia (somewhere between Onslow and Carnarvon, Western Australia) than Madagascar, as has been assumed by some writers. Whether Cano actually landed here is uncertain, but it may be taken for granted that in these days no ship could afford to neglect an opportunity of landing for the purpose of taking in water.

TORRES

A Spanish expedition under ALVARO MENDANA DE MEYRA, with PEDRO FERNANDEZ DE QUIROS as second in command, sailed from Callao on 9th April, 1595, and discovered the island of SANTA CRUZ (lat. 11° S., long. 166° E.), where an attempt was made to establish a colony. The result was a disastrous failure, and Mendana's death took place soon after. WYTFLIET'S MAP (1597[1]) shows, in the same latitude as the southmost Solomon Islands (10° S.), a strait dividing Nova Guinea and Terra Australis, and this is actually the latitude of Torres Strait. The map has a note stating that TERRA AUSTRALIS is "SEPARATED FROM NEW GUINEA by a narrow strait. Its shores are hitherto but little known, since, after one voyage and another, that route has been deserted, and seldom is the country visited unless when sailors are driven there by storms." In this harmless statement, there is surely no ground for Collingridge's accusation of fraud on the part of the Dutch, or of a desire to filch the credit of the discovery of the strait. Collingridge adduces a good many fragments of evidence that both the Spanish and the Dutch were well aware of the existence of the strait before the end of the sixteenth century, but after Wytfliet's admission there was a growing tendency on the part of the Dutch to deny the existence of such a strait, and several failures on their part to verify it only strengthened this doubt. They doubted more and more until the question was finally settled by Cook in 1770.

[1) The Discovery of Australia, by George Collingridge, 4to, Sydney, 1895, p. 218.]

{Page 10}

That the strait was known to Spaniards early in the seventeenth century is proved by a remarkable document, dating from somewhere between 1614 and 1621. This is a MEMORIAL which DR. JEAN LUIS ARIAS, a lawyer in Chili, writing on behalf of a number of priests, addressed to King Philip III, urging more vigorous exploration, on humanitarian and religious grounds. NEW GUINEA is referred to in it as "a Country ENCOMPASSED WITH WATER."

QUIROS, who persisted for years in urging the colonisation of Santa Cruz and the further exploration of the South Land, was at last given the command of an expedition, which left CALLAO, Peru, on 21st December, 1605. He hoisted his flag on the "San Pedro y San Pablo" (usually referred to in narratives as "El Capitano," or the Flagship), with, as his Captain or Chief Pilot, JUAN OCHAO DE BILBAHO. This officer was not a man of his own choice, but was forced upon him by the Viceroy at Lima, whose relative and protegé he was. In the course of the voyage he was disrated and replaced by the Junior Pilot GASPAR GONZALEZ DE LEZA. TORRES commanded the "San Pedro" (usually called, "for short," the "Almirante," or Lieutenant's ship). A zabra, or tender, named the "Tres Reyes," was in charge of PEDRO BERNAL CERMEÑO.

The flagship parted company with her consorts at the island of Espiritu Santo, and thereafter the two fragments of the expedition pursued separate courses. It is only with the section commanded by TORRES that the historian of the Cape York Peninsula is directly concerned, but the full significance of Torres' voyage cannot be correctly estimated without some consideration of the events which preceded the separation.

Quiros and Torres were among the last of Spain's navigators of the first order: by the time their expedition set out, Spain's influence in the Pacific was on the wane. The records of their experiences met with the usual fate of such documents. In accordance with what had become almost a matter of routine, they were at first jealously kept secret. Pigeon-holed, they were in due time forgotten, only to be unearthed, piece by piece, through the diligence of patriots, politicians and historians. In reviewing the progress of discovery subsequent to Quiros and Torres, it is necessary to remind ourselves that at any given date the information available was limited to such documents as had come to light, and the problems confronting new explorers were not at all those which would have been before them had they been fully aware of what had already been done. It may be confidently asserted that had the various reports of Quiros and Torres been given to the world in their true chronological order, the course of history would have differed widely from what it has been. Up to comparatively recent times the achievements of Quiros were only known at second hand, and chiefly through the meagre references by Torres, Arias and

{Page 11}

Torquemada. It was only in 1876 that the text of QUIROS' VOYAGE was given to the world by JUSTO ZARAGOZA, whereupon clouds of tradition and misconception were dispelled. Practically the whole of the Quiros documents have been skilfully marshalled by the late SIR CLEMENTS MARKHAM for the Hakluyt Society in the two volumes published in 1904. The chief items in the QuirosTorres bibliography are enumerated in the footnote.[1]

On leaving Callao, the expedition steered WSW. into 26° south latitude, somewhere in the vicinity of Easter Island, when, from considerations of the lateness of the season and other reasons, Quiros turned his ships towards WNW. His original intention had clearly been to go much further south, as may be seen from the text of his directions to Torres:—

"You are to be very diligent, both by day and night, in following the 'Capitano' ship, which will shape a WSW. course until the latitude of 30° is reached, and when that is reached, and no land has been seen, the course will be altered to NW. until the latitude of 10° 15'; and if no land has yet been found, a course will be followed on that parallel to the west in search of the Island of Santa Cruz. There a port will be sought in the bay of Graciosa, in 10° of latitude and 1,850 leagues from the city of The Kings [Lima] to the South of a great and lofty volcano standing alone in the sea, about 8 leagues from the said bay. The Captain who arrives first in this Port, which is at the head of the Bay, between a spring of water and a moderate-sized river,

[1) Historia del Descubrimiento de las Regiones Austriales hecho por el General Pedro Fernandez de Quiros, publicado per Don Justo Zaragoza, 3 vols. Madrid, 1876. This document was written by Quiros' Secretary Luis de Belmonte Bermudez, and signed by Quiros for authentication. (English translation by Markham, 1904.)

The Voyages of Fernandez de Quiros, 1595-1606, translated and edited by Sir Clements Markham, 2 vols., 1904. Hakluyt Society.

True Account of the Voyage that the Captain Pedro Fernandez de Quiros made by order of His Majesty to the Southern Unknown Land, by Gaspar Gonzalez de Leza, Chief Pilot of the said Fleet (translated by Markham, 1904). Corroborates Bermudez. The author confines himself to facts, courses and latitudes, and ignores the insubordination or mutiny.

Torquemada's Voyage of Quiros, Seville, 1615 (translated by Markham, 1904). A sketchy account compiled from the documents available in 1615.

Torquemada is to Quiros as Hawkesworth to Cook.

Relation of Luis Vass de Torres, concerning the Discoveries of Quiros, as his Almirante [Lieutenant]. Manila, July 12th, 1607. A copy fell into the hands of Alexander Dalrymple, 1762, and he published the Spanish text in Edinburgh in 1772. Dalrymple afterwards translated the Relation into English, and it was first printed in Burney's Discoveries in the South Seas, 1806. Reproduced by Collingridge and also by Markham.

Charts of Diego de Prado y Tobar. Sent from Goa in 1613. They are four in number and represent (1) Espiritu Santo, and (2, 3, and 4) Localities in Southern New Guinea, and give the dates of the discoveries.

Markham observes:—"All the maps are signed by Diego de Prado y Tobar, who thus claims to be their author. The Surveys were no doubt made by Torres himself or by his Chief Pilot Fuentiduefias. Prado y Tobar may have been the draughtsman." The charts were discovered about 1878, and were reproduced by Collingridge and Markham.

Two letters to the King sent by de Prado 24th and 25th December, 1613, enclosing the above charts, and also a general chart of Torres' Discoveries (which has not been found). Printed by Collingridge and Markham.

The Arias Memorial (1614-1621).

A Voyage to Terra Australis in the Years 1801, 1802 and 1803 in His Majesty's Ship the "Investigator," by Matthew Flinders, R.N., 2 vols, fcp. London, 1914, vol. i., pp.vii, x, xi.

See also, The Discovery of Australia before 1770, by George Collingridge, 4to. Sydney, 1895. The First Discovery of Australia and New Guinea, by George Collingridge. Sydney, 1906. The Part borne by the Dutch in the Discovery of Australia, by J. E. Heeres, LL.D. Leiden and London, 1899. Life of Tasman, by J. E. Heeres, fol. London, 1898.]

{Page 12}

with bottom from 40 to 35 fathoms, is to anchor there and wait there three months for the other two ships. When together, a resolution will be taken as to what further shall be done, in compliance with His Majesty's orders. If by chance the other ships do not arrive, the Captain before he departs, is to raise a Cross, and at the foot of it, or of the nearest tree, he is to make a sign on the trunk to be understood by him who next arrives, and to bury a jar with the mouth closed with tar, and containing a narrative of all that has happened and of his intentions. Then he will steer SW. as far as 20°, thence NW. to 4°, and on that parallel he is to steer West in search of New Guinea. After coasting all along that land, he is to proceed to the Country of Manila, by the Island of Luzon of the Philippines, in 14° North, thence by the Eastern Indies to Spain."

Much confusion has arisen, and much speculation has been indulged in, owing to a doubt as to the correct interpretation of references by Torres to the "prescribed latitude." The general and very natural impression has hitherto been that Quiros was under orders not to turn north until he had reached a certain southern latitude, the precise situation of which he and Torres were ordered to keep secret.

The narrative of Bermudez (as the mouthpiece of Quiros), only recently given to the world, proves conclusively that there was no mystery and no intentional concealment. Quiros, as a matter of fact, received no orders from Spain, and the valedictory epistle of the Governor of Peru did not restrict his discretionary powers.

The expedition was manned by 130 seafarers and six priests. The flagship and the "Almirante" were vessels of 150 and 120 tons respectively.

QUIROS had barely gone to sea when he began to be ill, and he was more or less of an invalid during the whole of the voyage. From the occasional references to headaches and other symptoms, a layman would conjecture that he had got a "touch of the sun" at Lima. At all events, he was frequently too ill to take his proper place of command and was under the necessity of leaving to subordinates many decisions which were among his own obvious duties. The narrative (written, it must be remembered, by a faithful admirer) naïvely shows him to have been by turn querulous, weak, timid and vacillating, although ever honestly and even zealously solicitous for the glory of his God and the advantage of his King. His sentiments, as reported by Bermudez, were humane, honourable and far ahead of his time, and I do not think they were cant, such as flowed readily enough from the pens of some previous and contemporary navigators. His shortcomings may charitably, and I think justly, be set down as symptoms of his malady.

The too early abandonment of the initial WSW. course was unfortunate for Quiros, who, had he persevered, would probably have anticipated Tasman's discovery of New Zealand. Torres protested against it and endeavoured to induce Quiros to carry out his original intention of touching 30° S. before "diminishing his latitude," but to no purpose.

{Page 13}

There is reason to believe that Quiros was influenced in his decision to steer WNW. no less by the insubordinate, if not mutinous, conduct of a section of his crew than by the lateness of the season. Probably enough, with a commander of greater firmness, the ugly word "mutiny" would never have been heard.

Having reached, approximately, the latitude of 10° S., the expedition steered west for VERA CRUZ, driven by the imperative need for fresh water and firewood. These requisites, however, were obtained at an island named TOUMACO, and the project of making for Vera Cruz was abandoned.

By this time, the INSUBORDINATION on the flagship had to be dealt with. The ringleader was the Chief Pilot, or Captain, JUAN OCHOA DE BILBAHO, for whom Quiros considered that a sufficient punishment was to be relieved of his office and sent on board the "Almirante"—a proceeding which was perhaps a little hard on Torres. Ochoa was replaced by GASPAR GONZALEZ DE LEZA, Junior Pilot.

A bitterly spiteful enemy of Quiros, and necessarily a supporter of the disrated Captain, was DIEGO DE PRADO Y TOBAR, who, according to his own account, voluntarily accompanied Ochoa and boarded the "Almirante" at Toumaco. In allowing an officer of the flagship t0 desert openly and to side with a degraded malcontent, it seems to me that Quiros displayed a weakness which was most reprehensible, unless it was to be pardoned as a "symptom" of his illness. Be this as it may, we owe to the desertion of Prado, as will afterwards appear, a much fuller knowledge of Torres' subsequent proceedings than we should have had if Prado had not accompanied Torres for the remainder of the expedition. In the letters already referred to, Prado states that: "I went as Captain of the ship Capitano,' knew what took place on board and took part in it, and as it was not in conformity with the good of Your Majesty's Service, I could not stay. So I disembarked at Toumaco and went to the Almirante,' where I was well received." The assertion that he was Captain is sheer impudence, as there can be no question that the Captain was Ochoa. Prado was perhaps a mate" of some sort, and the sailing of the ship may at some time have temporarily devolved upon him in the course of duty, but beyond this there was never any justification for his claim. His version of the story is that he gave Quiros timely warning of the mutinous disposition of the "Capitano's" officers and crew, and he insinuates that Quiros either did not believe him or stood so much in fear of the malcontents that he made things so unpleasant that he (Prado) was glad to exchange into the "Almirante."

At Toumaco, the natives were understood to say that large lands (which, of course, might prove to be the desired South Land) lay to the south, and the course was changed accordingly. In latitude 15° 40' S. and longitude 176° E., the promised land

{Page 14}

seemed to have been reached at last, on 30th April, 1606. Good harbourage was afforded by the GRAN BAYA DE SAN FELIPE Y SANTIAGO (Saints Philip and James), otherwise the Port of VERA CRUZ (True Cross), thus going one better than Mendano with his Santa Cruz (Holy Cross). On the banks of the JORDAN RIVER, at the head of the bay, the site for the great colonial city, the NEW JERUSALEM was selected. The country was at first called the Land of ESPIRITU SANTO (Holy Ghost), but as Quiros became convinced that it was part of the great Southern Continent, he expanded the title to AUSTRALIA DEL ESPIRITU SANTO, [1] and took formal possession, in the name of his Sovereign, of "all lands then seen, and still to be seen, as far as the South Pole." The grandiose names bestowed illustrate not only the innate piety but also the weakness for superlatives which characterised the Spaniard of the seventeenth century.

It has been argued (e.g., by the late Cardinal Moran) that Quiros, with three ships under his command, could not have spent five weeks at the Island of Santo without discovering that it was no part of a continent. The fact remains that he did believe it to be continental, although from the first Torres did not agree with him. Quiros approached the island predisposed to believe as he did. The elaborate ceremony which marked his stay, including the nomination of municipal officers, the erection of a votive church and the inauguration of an order of Knighthood of the Holy Ghost, sufficiently attested the sincerity of his belief. The ceremonies and the hopes to which they testified were, indeed, as Sir Clements Markham observed, in the light of our present knowledge, not a little pathetic.

In after years the conviction obsessed him, till he besought his King and the world to believe that he had added to the Spanish Crown a territory of hardly less importance than that gained by the discoveries of Columbus. He died, broken-hearted, shouting this belief into deaf ears.

The argument that Quiros had time enough to ascertain that Santo was an island is sufficiently answered by the fact now clearly discernible from the narrative of Bermudez, that the exploration which took place during the five weeks was confined to the "Gran Baya" and its environs, and that Quiros, in the flagship, was never outside of the bay until the day when he finally departed from it, to be driven out of sight of land and separated from his two consorts. Unexpected confirmation of this fact is supplied by the CHART OF THE GRAN BAYA (brought to light as recently as 1878) signed by PRADO, which shows so many anchorages inside the bay that it may easily be believed they account for as many of the

[1) Markham supports the view that the name should read—as it sometimes does, spelling in the seventeenth century being capricious—Austrialia, a claim to Austria being signified in one of the titles of the King of Spain.]

{Page 15}

thirty-five days as were not spent ashore. The chart, whether the credit of the surveying or only of the draughtsmanship belongs to Prado, agrees so well with modern Admiralty Charts of that portion of the island, that there can be no question of the accuracy of Captain Cook's identification—made, of course, without the assistance of Prado's Chart, which, in 1770, lay unknown in the Spanish archives.

Sir Clements Markham, for many years President of the Royal Geographical Society, had no difficulty in admitting the honesty of Quiros' belief that he had discovered the southern land, and wrote of his approach to the Island of Espiritu Santo:—

"Island after island, all lofty and thickly inhabited, rose upon the horizon, and at last he sighted such extensive coast-lines that he believed the Southern Continent to be spread out before him. The islands of the New Hebrides Group, such as Aurora, Leper, and Pentecost, overlapping each other to the south-east, seemed to him to be continuous coast-lines, while to the south-west was the land which he named Austrialia del Espiritu Santo. All appeared to his vivid imagination to be one continuous continental land."

The expedition, as has been mentioned, remained in the Bay of Saints Philip and James for thirty-five days, viz., from 3rd May to 8th June, 1606, the numerous anchorages laid down on Prado's chart showing how thoroughly the shores must have been examined. The sailors made themselves very much at home and behaved with such arrogance, cruelty and rapacity that the natives treated them with well-merited hostility, and although Quiros "deplored" such excesses, he seems to have taken no suitable steps to stop them, beyond formally prohibiting profane swearing and other unseemly practices. It is noteworthy that the outrageous conduct of Prado was so far condoned that he figured in the list of officers of the municipality of the New Jerusalem as Depositario General. This term is translated by Markham as "General Storekeeper," but in my opinion, the fact that Prado carried off with him, among other things, the manuscript, or at least a copy, of the new chart of the bay and its environs, favours the view that the office held by him was the more responsible one of receiver or recorder.

The three vessels left the bay on 8th June, presumably with the intention of coasting along the continent to the north-west, or, should Espiritu Santo prove to be a cape, of running south-west to 20° S. north-west to 4°, and west on that parallel to the coast of New Guinea, given an open sea, in accordance with the spirit of the instructions given to Torres for his guidance in the event of a separation. As soon, however, as they cleared the cape which formed the north-western horn of the bay, they met with a strong wind from the south-east and endeavoured to get back into the bay for shelter. In this attempt the "Almirante" and the tender succeeded, but the FLAGSHIP was blown further and further to

{Page 16}

leeward and in the morning succeeding the first night was out of sight of land and hopelessly SEPARATED FROM HER CONSORTS. Quiros

himself was "below," too ill to direct the conduct of his vessel. Prado asserts, indeed, that Quiros was a prisoner in the hands of mutineers, but as he was not on board and could only have obtained his information at second hand, and, moreover, was prejudiced and malicious, the statement may be disregarded. Quiros himself, as he complained, had enemies on board, discontented and sulky, but there can be no doubt of the loyalty and devotion of his new Captain, de Leza, and his Secretary, Bermudez, who, perhaps jointly, conducted affairs during Quiros' incapacity.

The "Capitano," having reached 10° S., the latitude of Santa Cruz, without seeing the island, being probably between it and the Solomon Group, it was resolved on 18th June to make for Acapulca. unless some friendly port should first be discovered suitable for refitting and repairing the ship. On a NE. by N. course the line was crossed on 2nd July. The course was shortly altered to NE., and lay, in all probability, between the Marshall and Gilbert Islands. Having reached 38° N. latitude, the vessel steered ESE. until North American land was sighted in 34° on 23rd September. The Mexican coast was then followed to the SE. and Acapulca was reached on 23rd November, 1606. Only one death occurred during the voyage, that of an old priest. Quiros, who landed without resources, was coldly received. He, however, managed to reach Madrid on 9th October, 1607. The remainder of his life was spent in making passionate appeals to the King for the means to prosecute his discoveries and develop the imaginary continent in the interests of Spain. Wearied by his importunities, the Government got him out of the way by giving him an open letter to the Governor at Panama, who was instructed to assist him to his object, at the same time sending an0ther letter in which the Governor was secretly instructed to string him on and delay him ad infinitum. Fortunately for himself, he died on the voyage to Panama (1609-1610) unaware of the treachery of which he was to be the victim. He was only fifty years of age, but was, says Markham, "worn out and driven to his grave by Councils and Committees with their futile talk, needless delays and endless obstructions."

The flagship having disappeared, TORRES waited and searched for it for fifteen days, before feeling himself free to form his own plans for carrying out the instructions given him by Quiros. He weighed anchor on 26th June, and commenced the voyage which took him through the passage on which Dalrymple afterwards conferred the name Of TORRES STRAIT.

Torres' relation or report on this voyage occurs in the form of a letter from Manila, dated 12th July, 1607, addressed to the King of Spain, and is, so far as is known, the first recorded account of the passage of Torres Straits. Had this report been published

{Page 17}

at once future explorers would have followed different lines from those now marked by history. We have already seen how this report disappeared. There are indications that Robert de Vaugondy had got some inkling of it, or of charts relating to it, between 1752, when his map of the region showed no strait, but only a "bight" on the western side (the Dutch idea), and 1756, when his map showed the strait. The report was, in fact, discovered at Manila[1] in 1762, when a copy fell into the hands of Alexander Dalrymple, who printed the Spanish text in Edinburgh in 1772, as an appendix to his Charts and Memoirs. He had not, apparently, mastered its contents, or grasped its significance, in 1770. Years later,. he translated it into English, and permitted Captain James Burney to print the translation in his Discoveries in the South Seas in 1806. Dalrymple, in fact, only knew of Torres' achievement at second hand, and chiefly through the references of Arias, when Cook sailed in the "Endeavour" in 1768.

Up to the last quarter of the eighteenth century, the references to the voyages of Torres, second hand and unauthenticated as they were, contained in Arias' Memorial (written between 1614 and 1641) were practically all that were known to the world of Torres and Torres Strait.