|

Project Gutenberg

Australia a treasure-trove of literature treasure found hidden with no evidence of ownership |

BROWSE the site for other works by this author (and our other authors) or SEARCH the entire site with Google Site Search |

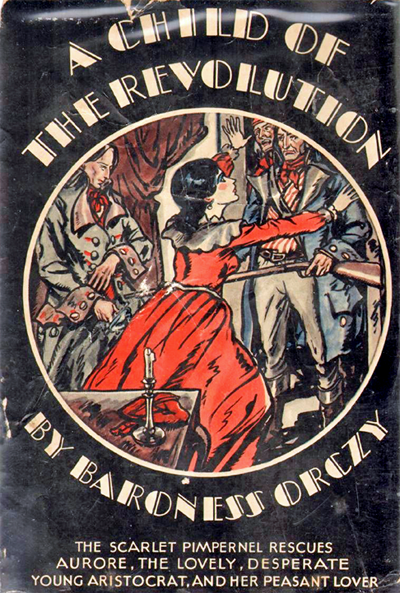

Title: A Child of the Revolution Author: Emmuska Orczy * A Project Gutenberg of Australia eBook * eBook No.: 0602771h.html Edition: 1 Language: English Character set encoding: Latin-1(ISO-8859-1)--8 bit Date first posted: July 2006 Date most recently updated: June 2020 This eBook was produced by: Richard Scott and Colin Choat Project Gutenberg of Australia eBooks are created from printed editions which are in the public domain in Australia, unless a copyright notice is included. We do NOT keep any eBooks in compliance with a particular paper edition. Copyright laws are changing all over the world. Be sure to check the copyright laws for your country before downloading or redistributing this file. This eBook is made available at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg of Australia License which may be viewed online at http://gutenberg.net.au/licence.html

GO TO Project Gutenberg of Australia HOME PAGE

Foreword

Book One

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Book Two

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

Chapter 13

Chapter 14

Chapter 15

Chapter 16

Chapter 17

Chapter 18

Chapter 19

Chapter 20

Chapter 21

Chapter 22

Chapter 23

Chapter 24

Chapter 25

Chapter 26

Chapter 27

Chapter 28

Book Three

Chapter 29

Chapter 30

Chapter 31

Chapter 32

Chapter 33

Chapter 34

Chapter 35

Chapter 36

Chapter 37

Chapter 38

Chapter 39

Chapter 40

Book Four

Chapter 41

Chapter 42

Chapter 43

This is the story which Sir Percy Blakeney, Bart., told to His Royal highness that evening in the Assembly Rooms at Bath.

The talk was of the recent events in France, the astounding fall of Robespierre: the change in the whole aspect of the unfortunate country: and His Royal Highness expressed his opinion that among all those men who had made and fostered the Revolution, there was not one who was anything but a scoundrel, a reprobate, a murderer, and worker of iniquity.

Sir Percy then remarked: "I would not say that, sir. I have known men—"

"You, Blakeney?" His Royal Highness broke in, with an incredulous laugh.

"Even I, sir. May I tell you of one, at least, whose career I happened to follow with great interest?"

And that is how the story came to be told.

"In Heaven's name, what has happened to the child?"

This exclaimed Marianne Vallon when, turning from her wash-tub, she suddenly caught sight of André at the narrow garden gate.

"In Heaven's name!" she reiterated, but only to herself, for Marianne was not one to give vent to her feelings before anyone, not even before her own son.

She raised her apron and wiped her large, ruddy face first and then her big, capable hands, all dripping with soapsuds; after which she stumped across the yard to the gate: her sabots clacked loudly against the stones, for Marianne Vallon was a good weight and a fair bulk; her footsteps were heavy, and her movements slow.

No wonder that the good soul was, inwardly, invoking the name of Heaven, for never in all his turbulent life had André come home looking such a terrible object. His shirt and his breeches were hanging in strips; his feet, his legs, the whole of his body, and even his face, were plastered with mud and blood. Yes, blood! Right across his forehead, just missing his right eye, fortunately, there was a deep gash from which the blood was still oozing and dripping down his nose. His lip was cut and his mouth swollen out of all recognition.

"In Heaven's name!" she reiterated once more, and aloud this time, "thou little good-for-nothing, what mischief hast thou been in in now?"

Marianne waited for no explanation; obviously the boy was not in a fit state to give her any. She just seized him by the wrist and dragged him to her washtub. It was not much Marianne Vallon knew of nursing or dressing of wounds, but her instinct of cleanliness probably saved André life this day, as it had done many a time before. Despite his protests, she stripped him to the skin; then she started scrubbing.

Soap and water stung horribly, and André yelled as much with impatience as with pain; he fought like a young demon, but his mother, puffing like a fat pug dog, imperturbable and energetic, scrubbed away until she was satisfied that no mud or dirt threatened the festering of wounds. She ended by holding the tousled young head under the pump, swilling it and the lithe, muscular body down with plenty of cold water.

"Now dry thyself over there in the sun," she commanded finally, satisfied that in his present state of dripping nudity he couldn't very well get into mischief again. Then, apparently quite unruffled by the incident, she went back to her washtub. This sort of thing happened often enough; sometimes with less, once or twice with even more disastrous results. Marianne Vallon never asked questions, knowing well enough that the boy would blurt out the whole story all in good time: she didn't even glance round at him as he law stretched out full length, arms and legs outspread, as perfect a specimen of the young male as had ever stirred a mother's pride, the warm July sun baking his skin to a deeper shade of brown and glinting on the ruddy gold of the curls which clustered above his forehead and all around his ears.

"What a beautiful boy!" strangers had been heard to exclaim when they happened to pass down the road and caught sight of André Vallon bending to some hard task in garden or field.

"What a beautiful boy!" more than one mother in the village had sighed before now, half in tenderness, half in envy. And "André Vallon is so handsome!" tall girls not yet out of their teens would whisper, giggling, to one another. If Marianne Vallon's heart swelled with pride when she overheard some of this praise, she never showed it. No one really knew what went on behind that large red face of hers, which some wag in the village had once compared to a bladder of lard. People called her hard and unfeeling because she was not wont to indulge in those "Mon Dieu!'s" and "Sainte Vierge!'s" when she passed the time of day with her neighbours, or in any of the "Mon chou"'s and "Mon pigeon"'s when she spoke to her André.

She just went about her business in and around her cottage, or at the château when she wanted up there to do the washing, uncomplaining, untiring, making the most of the meagre pittance which was all that was left to her now of a once substantial fortune. Her husband had died a comparatively rich man—measured by village standards, of course. He had left his widow a roomy cottage, with its bit of garden and a few hectares of land whereon she could plant her cabbages, cultivate her vines, keep a few chickens and graze a cow. But, bit by bit, the land had to be sold in order to meet the ever growing burden of taxes, of seignorial dues, to be paid by those who had so little to others who seemed to have so much, of tithes and rents and rights, all falling on the shoulders of the poor toilers of the land, while the seigneurs were exempt from all taxation. Then came two lean years—drought lasting seven months in each case, resulting in a total failure of the crops and poor quality of the wine. André was ten when the last piece of land was sold, which his father had acquired and his mother tended with the sweat of her brow; he was twelve when first he saw his mother stooping over her own washtub. Hitherto, Annette from down the village had come daily to do the rough work of the household; then one day she didn't come. André took no notice. It was nothing to him that at dinner-time it was his mother who brought in the soup tureen, that it was she who carried away the plates and the knives, and that she disappeared into the kitchen after dinner instead of sitting in the old wing chair sipping her glass of wine, the one luxury she had indulged in of late. Annette or Maman, what cared he who brought him his dinner? He was just a child.

But when he saw his mother at the washtub with a huge coarse apron round her portly person, her sleeves tucked up above those powerful arms, the weight of which he had so often felt on the rear part of his person when he had been a naughty boy, then he began to ask questions.

And Marianne told him. He was only twelve at the time, and she did not mince matters. The sooner he knew, the better. The sooner he spared her those direct questions and those inquiring looks out of his great dark eyes, the sooner, she thought, would he become a fine man. So she told him that the patrimony which his father had left in trust for him had all dwindled away, bit by bit, because the tax collector's visits were getting more and more frequent, the sums demanded more and more beyond her capacity to pay. There were the imposts due to the seigneur, and the tallage levied by the King; there were the rates due to the commune, and the tithes due to the Church.

Pay! Pay! Pay! It was that all the time. And two years' drought, during which the small revenues from the diminished land had shrunk only two palpably. Pay! Pay! Pay! And there were the seignorial rights. No corn or wine or live stock allowed to be sold in the market until Monseigneur's wine and corn and live stock, which he wished to sell, had all been disposed of. No wine press or mill to be used, except those set up by Monseigneur and administered by his bailiffs, who charged usurious prices for their use. Pay! Pay! Pay! It was best that André should know. He was twelve—almost a man. It was time that he knew.

And André had listened while Maman talked on that cold December afternoon three years ago, when the fire no longer blazed in the wide-open hearth because wood was scarce and no one was allowed to purchase any until Monseigneur's requirements were satisfied. André had listened, with those great inquiring eyes fixed upon his mother, his fingers buried in the forest of his chestnut curls, and his brows closely knit in the great endeavour to take it all in. He wanted to understand; to understand poverty as his mother explained it to him: the want of flour with which to make bread, the want of wood wherewith to make a fire, even the want of a bit of thread or a needle, simple tools with which his breeches and shirts—which were forever torn—could, as heretofore, be mended.

Poor? Yes, he was beginning to understand that he and Maman were now poor as Annette and her father down in the village were poor, so that Annette had to go and scrub floors in other people's houses and wash other people's soiled linen so as to bring a few sous home every day wherewith to buy salt and bread. Not that this primitive idea of poverty worried the young brain overmuch. It was not like a sudden descent from affluence to indigence. It was some time now since his favourite dishes had been put upon the table and since he had last wore a pair of shoes. The descent into the present slough of want had been very gradual, and, childlike, he had not noticed it.

Nor did his mother's lengthened homily make a very deep impression upon his mind. From a race of children of the soil he had inherited a sound measure of philosophy and a passionate love of the countryside. While he could run about in the meadows, or watch the rabbits at evening scurrying away across the fields, while he could pick black berries in the hedgerows and gather the windfalls in the neighbouring orchards, while he could scramble up the old walnut trees and furtively touch the warm smooth eggs in the nests among the branches, he was perfectly happy.

What he didn't like was when Marianne set him to do the tasks which used to devolved on Annette. He didn't like scrubbing the kitchen floor, and he hated wringing out the linen and hanging it up to dry. But it never as much entered his dead to disobey. Mother was not one of those whom anyone had ever though of disobeying, André least of all. She was large and fat and comfortable, and—especially in the olden days—she loved a good joke and would laugh heartily till the tears rolled down her fat cheeks, but she knew how to use the flat of her hand, as André had often learned to his cost. She was not one of those who believed in sparing the rod, and many a time had André gone to sleep on his narrow plank bed lying on his side because it hurt him to lie on his back.

But the fear of his mother's heavy hand did not really keep him out of mischief. As he grew older the desire for mischief grew up with him. A vague sense of injustice would, moreover, inflame that desire until it led him to acts which caused not only Mother's hand to descend upon him, but, also, of a certain hard stick, which was very painful indeed. That time when he chased Lucile Godart, the miller's daughter, all down the road and then kissed her in sigh of Hector Talon, her fiancé, who was short, fat, and bandy-legged, and was too slow in his movements to come to her rescue, was a memorable occasion, for, though Hector had not felt sufficiently valiant to administer punishment to the young rascal, godar, the miller, had no such qualms. And André got his punishment twice over, Mother's being by far the more severe. But he said that it was worth it. To kiss a girl, he declared, when she is placid and willing was well enough, but when she was a little spitfire like Lucile and fought and scratched like a wildcat, then to hold her down, kiss her throat and shoulder and, finally, her mouth, that was as great a lark as ever came a man's way—and well worth a whipping, or even two. What Lucile thought about it he neither knew nor cared.

The incident with Lucile Godart had occurred two years ago. André was thirteen then, and already the girls were wont to blush when their eyes met his, so dark and bold.

Since the Lucile had married her Hector, who was now an assistant bailiff on Monseigneur's estate and lived with his young wife in a stone house on the edge of the wood. At the side of the house there was a field, which at eventide was alive with rabbits. That field exercised an irresistible fascination over André Vallon. He would cower behind the hedge and for hours watch the little cottontails bobbing in and out of the scrub. More than once he had been warned off by Hector Talon; once he had actually been caught unawares and driven off with some hard kicks.

But to-day a tragedy had occurred.

Lying on his back at this moment on the hard stones not far from his mother's washtub, and in the state in which God first made him, he was perhaps wondering whether in this instance the game was going to be worth the candle. He was too old now to get a whipping from Mother, and he did not think that what he had done was punishable by law. Still, Hector Talon was a spiteful beast, and Lucile...Well, the little she-devil would get her deserts one day, on the faith of André Vallon.

While the hot July sun was baking his skin and staunching the blood of his wounds, his brain was working away on the possible consequences of to-day's adventure. He wondered what his mother thought about it. For the moment she appeared to be immersed, both with hands and with mind, in her washtub. Her broad back was turned towards him, and André thought that it looked uncompromising. Still, Mother would have to know sooner or later, so better now, perhaps, while she was busy with other things. And before he knew that he had begun to think aloud, words were pouring out of him a kind of passionate outburst of resentment.

"Rabbits! Rabbits!...Why! there are thousands and thousands of them in that field," he went on with childish sense of exaggeration. "M. Talon himself is obliged to put fencing round his kitchen garden to keep them away. And I didn't put up any snare or trap—I swear I didn't. There was nobody about, and I just got over the fence to see...Well, I don't know. I just did get over the fence, and there in the long grass was the tiniest wee rabbitkins you ever saw! He was all crouching together till he looked like a ball of brown fur, and his round eyes were wide open, looking—I suppose he was horribly frightened—so frightened that he couldn't move. Anyway, I just stooped to pick him up. The house was all quiet, there didn't seem to be any one at home, and that brute of a dog of theirs was on the chain."

André paused a moment; his hand had gone mechanically up to his forehead, to his lips, his shoulder, all of which were smartin horribly. Perhaps, he thought, it was time Mother said something, but she just went on with her washing, and all that André saw of her was that large, uncompromising back.

"How could I guess?" the boy went on; and suddenly he sat up, his brown arms encircling his knees, his chest striped with the red of the blood oozing from his shoulder. "How could I guess that that little vixen Lucile was spying from the window? I had got the young beggar by the ears, and I remember just thinking at the moment what luscious strew he was going to make. Of course, I had no intention of putting him down again, and I was trying to tuck him out of sight inside my shirt. And then, all of a sudden, I heard Lucile's voice calling to that dog of hers: 'Hue! César! hue!' What a devil! My god! what a devil! That great brute César! He was on me before I could drop the rabbit and take to my heels. He was on me and got me on the shoulder. Then I did drop the rabbit, and it scooted away. I wanted both my hands to defend myself. I knew it would be no use trying to run, and César would have had me by the throat if I hadn't got him. And there was that little devil Lucile, running down the field and shouting, 'Hue! hue!' all the time."

André was warming to his story. He was fighting his battle with César over again. His nostrils quivered; perspiration glistened on his forehead; his eyes, wide open and dilated, were as dark as the blackberries in the hedgerows.

"I got César by the throat," he went on in a shaky, hoarse voice, his words coming out jerkily, interspersed with gasps that were half laughter and half tears. "I squeezed and I squeezed, and all the while his horrid hot breath made me feel so sick that I thought I should have to let go. Once he got me on the forehead, and once I felt his nasty slimy teeth right inside my mouth. That gave me the strength to squeeze tighter, for I thought that I didn't he would probably kill me. Then that little devil Lucile began to laugh, and I could hear bits of words that she said, 'That will teach you to insult honest girls. César also thinks it a lark to get a boy down a kiss him on the shoulder, what? And on the mouth. Hue, César! hue!' Isn't she a troll, Mother, a witch, a vixen, a she-devil, nursing vengeance like this for two years—or is it three?—but I'll kiss her again. I will! And what's more, I will..."

Once more André paused. His mother's broad back was still turned towards him, but she had turned her head, and through the corner of her eye she was looking at him. That is why he did not complete the sentence or put into words the ugly thought that had taken root in his brain. He remained quite still and silent for a moment or two, then he said abruptly:

"I never let go of César's throat till I had squeezed the life out of him."

But at this bald statement of fact, Marianne Vallon's outward placidity gave way. "Jésus! Mon Dieu!" she exclaimed, and faced that naked young daredevil with horror and anxiety distorting her squab features. "Not content with poaching in M. Talon's field, thou hast killed his dog?"

"He would have killed me else. Would'st rather César had killed me, Mother?" André retorted with an indifferent shrug of his lean shoulders.

"Don't be a fool, André!" Marianne Vallon went on once more, in her usual placid way. "M. Talon—dost not know it?—has only to go before the magistrate and denounce thee--"

"Well, they can't hang me for killing a dog in self-defense, and I didn't poach the rabbit."

"No, but they can..."

It was the mother's turn to leave the phrase incomplete which involuntarily had come to her lips. Just like André a moment ago, she did not wish to put into words the thoughts that had come tumbling into her brain and were filling her heart with the foreknowledge of a calamity which she knew she could not avert.

If she could she would have packed André off somewhere, to friends, relations, anywhere; away from the spite of Talon, who already had a grudge against the child and who would feel doubly vindictive now. But when Marianne Vallon first fell on evil days she lost touch with her former friends or relations, who, in their turn, were content to forget her. André must stop at home and face the calamity like a man.

It came soon enough.

Talon, who was a man of consideration in the commune, laud a complaint before M. le Substitut against André Vallon for poaching and savage assault on a valuable dog, resulting in the latter's death.

André, in consideration of his youth—he was only fifteen—was condemned to be publicly whipped. M. le Substitut told him that he could consider himself most fortunate in being let off with so mild a punishment.

A blind unreasoning rage, an irresistible thirst for revenge; a black hatred of all those placed in authority; of all those who were rich, or independent, or influential, filled André Vallon's young soul to the exclusion of every other thought and every other aspiration.

He was only fifteen, and in his mind he measured the long years that lay before him in which he could find the means, the power, to be even with those who had inflicted that overwhelming shame upon him. It was not the blows he minded...Heavens above! that lithe, young body of his was inured to every kind of hardship, to every kind of pain. It was not the blows, it was the shame. Talon, who was influential and who was egged on by his wife, had prevailed upon the magistrate to make an order that all the inhabitants of the commune who were not engaged in work were to be present in the market place to see justice done on the young reprobate. And these were still the days when no one dared go against an order, however absurd and however unjust, framed by M. le Substitut du Procureeur Général.

Monseigneur also came in his coach and brought friends to see the spectacle. There were two ladies among them who put up their lorgnettes and stared at the straight, sinewy young body, so like a statue of the Hermes with its slender, perfectly modelled limbs and narrow hips, and its broad shoulders and wide chest, smooth and dark as if cast in bronze.

"But the boy is an Adonis!" one of the ladies exclaimed in ecstasy.

"Quelle horreur!" she exclaimed a moment later when the stripes fell thick and fast on the smooth back she had admired. The days were not yet very far distant when ladies of high degree would crowed on balconies and windows to watch the execution of conspirators who perhaps had been their friends before then.

But for André Vallon, the bitter, humiliating shame!

His mother was waiting for him when he got home. She had prepared a little bit of hot supper for him, to which sympathisers in the village had also contributed: things he liked—a little hot soup, a baked potato, a bit of bread and salts. André ate because he was a young, healthy animal and was hungry, but he never said a word. Silent and sullen, he sat and ate. Not a tear came to those big dark eyes of his, in which there burned a fierce hatred and an overpowering humiliation.

Marianne, of course, said nothing. It was never her way to talk. She saw to it that André had his supper, and when he had finished she took him by the wrist and led him to his little room at the back. She undressed him and washed and dried his poor aching young body; then she wrapped him up in one of her wide gingham skirts which had become soft as silk after many washings, and laid him down on his narrow plank bed with his head resting on an old coat of his father's, which had survived the dispersal of most of the household goods. Before she had finished tucking him up in her wool shawl he was asleep.

She watched for a moment or two the beautiful young face, with the blue-veined lids veiling in sleep the sullen, glowering look of the eyes; stooped and softly touched the moist forehead with her lips. Two heavy tears found their way down her furrowed cheeks; a heavy sigh came though the firm obstinate lips, and slowly she came down on her knees. With clasped hands flung across the bed, she remained kneeling there for some time, praying for guidance, for strength to fight a brave fight with this turbulent young soul, and for power to guide it in the path of rectitude.

This was the year of grace 1782, and Marianne Vallon, in common with many men and women in the land these days, was not blind to the tempest which already was gathering force in every corner of France, framed by the ardour of young enthusiasts with a grievance like her André, or by the greed of profligate agitators, soon to burst in all its fury, sweeping before it all the old traditions, the old beliefs, the old righteousness of this country and its people, and inflicting wounds that it would take centuries to heal.

M. le Curé de Val-le-Roi, in the province of Burgundy, where they make such excellent wine, was a kindly and worthy man. He came of a good family—the Rosemondes of Nièvre, and though his intelligence was perhaps not of the highest order, his piety was sincere and his human understanding very real.

On the tragic day of André Vallon's public punishment he stood beside the whipping post the whole time that Marius Legendre—the local butcher employed by the Commune to administer punishment to juvenile offenders—was lamming into the boy. André, with teeth set and eyes resolutely closed, appeared not to hear the Curé's gentle words, exhorting him to patience and humility.

Patience and humility, forsooth! Never was there a vainer exhortation.

It was only when it was all over and he was freed from the post that André opened his eyes and cast a glowering, rankling look around the market square. Legendre had thrown down the whip and was handing the lad his shirt and coat. André snatched them out of his hand, and Legendre—a worthy man, not unkind—smiled indulgently. The two gendarmes stood at attention, waiting for orders, their faces wooden and impassive. Part of the crowd had already dispersed: the men silent and sullen, the women sniffing audibly. The younger ones—girls and boys—muttered words of pity or of wrath. Monseigneur was standing beside the door of his coach, helping the ladies to step back into the carriage. One of them—the one with the largnette—cast a final backward glance at André; then piped in a high-pitched, flutelike voice:

"See, my dear Charles, so would a fallen angel have looked had the Almighty punished the rebels with thongs."

A man in the forefront of the crowd, close to Monseignuer's coach, laughed obsequiously at the sally. André saw him. It was Talon. Lucile stood beside her husband. When she met André's glance, she, too, gave a laugh, but quickly turned her head away. Then only did a groan rise from the boy's breast. It was a groan of an overwhelming, impotent rage. His breath came whistling through his teeth. He made a movement like a wild beast about to spring, but instinctively the gendarmes had already placed each a hand upon his shoulder and held him down. André was weak after the punishment, though he would not have admitted it even to himself; but his knees shook under him, and he nearly collapsed under the heavy hands of the gendarmes. M. le Curé murmured gentle words. "My son, remember that our Lord—"

André turned on him with a cry that was like a snarl. "Go away! Go away!" he muttered hoarsely. "I hate you."

But the Curé did not go away. He stayed to help the lad on with his shirt and coat; then, when André, avoiding the crowd, went staggering round a back street and then down the lane towards his mother's cottage, the kindly old priest followed him at a short distance, ready to render assistance should the boy be seized with giddiness and collapse on the way. Only when he saw Marianne standing at the narrow garden gate waiting for her son did he went his way back to his presbytery. Contrary to his usual habit, he did not take his breviary out of his pocket or murmur orisons while he walked. With his soutane hitched up around his waist, he strode along, obviously buried in thought, for now and again he would shake his head and then nod, as if in secret communion with himself.

The results of M. le Curé's agitation were, firstly, a lengthy interview with Monseigneur, and secondly a summons to Marianne Vallon to bring her son André up to the château. Monseigneur desired to see him.

André, of course, refused to go. "I hate him!" he declared when M. le Curé came to announce what he thought was great news for Marianne and the boy.

"Monseigneur," the priest had explained, "was interested. He is always so kind and so gracious, but when I spoke to him of André he was pleased to be genial, facetious; he toyed, as one might say, with the idea of doing something for the boy. Then there were the ladies. Madame la Marquise d'Epinay put in a word here and there, so charming she was, so sprightly. She spoke of André as the bronze Hermes, and though the latter we know is nothing but a heathen god, and I would not care to think that our André had any likeness to such idolatrous things, I could not have it in my heart to reprove the witty lady, especially as Monseigneur appeared more and more diverted. Then Mademoiselle Aurore came in—such a pretty child—her governess was with her, and I gathered at once she knew something about our André—domestics will talk, you know, my good Marianne—and Mademoiselle was even more interested than Monseigneur. She put her little hands together and begged and begged of her father that André might come up to the château, as she desired to see him. And Monseigneur, who since the death of Madame la Duchesse gives in to all the child's whims, gave me permission to bring our André to him."

The good Curé spoke thus lenghily and uninterruptedly, for Marianne, absorbed in her knitting, said never a word: she was never much of a talker, and André only glowered and muttered unintelligible words between his teeth. There was perhaps something a little unctuous, a little complacent in M. le Curé's verbiage. He was not forgetting that besides being the incumbent of this poor little village, he was also by birth a Rosemonde de Nièvre, and that by tradition and upbringing he belonged to the same caste as Monseigneur le Duc de Marigny de Borne, whose gracious sympathy in facour of "our André" he had been fortunate enough to arouse.

"I hate him! I will not go!" was all that could be got out of André that day. "You can drag me to that accursed château," he went on sullenly, "as you did to the whipping post, but willingly I will not go."

"But, my dear child," the Curé protested, "Monseigneur said—"

"Whatever he said," the boy broke in with a snarl, like an animal that is being teased, "may his words choke him!—I hate him!"

"You are overwrought and agitated, my boy," the priest said placing his well manicured podgy white hand on André's shoulder, who promptly shook it off. "When the good God and your dear patron saint have prevailed over your rebellious spirit, you will realize how much Monseigneur's kindness and Mademoiselle Aurore's intercession—"

"Don't speak to me of those women up at the château," André cried hoarsely, "or I shall see red!"

Marianne Vallon at this point put down her knitting. She knew well enough that to carry on the discussion any further to-day would only drive the boy to exasperation. All that he had gone through in the past few days had, in a way, made a man of him, but a man with all a child's unreasoning resentment at what he deemed an injustice.

M. le Curé took the hint. With characteristic tact he changed the subject of conversation, spoke to Marianne on village matters—the washing of surplices which she had undertaken to do for a small stipend, and finally took his leave, deliberately ignoring André's ill manners and glowering looks. At the door, however, he turned once more to where the boy sat, chin cupped in his hand, staring dully into the gathering shadows.

"Remember, my dear child," he said with gentle earnestness; all his small, worldly ways drowned in a flood of genuine sympathy, "that your future does not belong entirely to yourself: your sainted mother works her fingers to the bone so that you should be clothed and fed. She performs menial tasks to which neither by birth nor upbringing was she ever ordained. Think of her, my lad, before you spurn the hand that can help you up the ladder that may lead you to an honourable career and give you the chance of repaying part of your debt to her."

Mother and son spoke little to each other during the rest of the day. Marianne appeared more than usually busy with knitting and sewing and spoke even less than was her wont. After sundown André went out from a tramp in woods and fields. Ever since the fatal day he had made a point of wandering over the countryside only after dark. He dreaded to meet familiar faces in the country lanes, dreaded to see either compassion or ridicule in the glances that would meet his.

To-night his young soul was brimful with bitterness. Never before had he felt such an all-embracing hatred for everything, and every human being who had made possible the humiliation that had been put upon him. Childlike, he wandered down the lane past the house where lived talon and his wife, the prime authors of the whole tragedy. He stood for a long time looking at the house. There were lights in one or two of the window. The Talons were rich, they could afford candles. They were people of consideration. They got the ear of the Substitut and engineered his, André's, lasting disgrace. He hated them—hated their house, their garden, their flowers; he wished with all his might that some awful calamity would overtake them.

The fields around were bathed in moonlight; the air was fragrant and warm; a gentle breeze fluttered the branches of the forest trees, causing a gentle murmur to fill the night with its subtle sound. The scent of hay and clover rose from the adjoining meadows, and from the depths of the wood there came from to time the melancholy call of a night bird or the crackling of trigs under tiny, furtive feet.

Only a very few days ago André would have revelled in all that: the little cottontails scurrying past, the bard-door owl flying by with great flapping of wings; fantastically shaped clouds veiling from time to time the face of the moon. All would have delighted him, those few short days ago. Now he had eyes only for that house of evil. He watched its windows till the lights were extinguished one by one, and then wished once more with all his might that hideous nightmares should disturb the sleep of those whom he hated so bitterly.

When André finally turned to go home again, it was close on midnight. Coming in sight of the cottage, he was surprised to see that, contrary to his mother's rigid rules of economy, there was still a light in the parlour. He pushed open the door and peeped in. Mother was sitting sewing by the light of a tallow candle. She looked up as he came in and gave him a welcoming smile. He thought she looked quite old, and her eyes were circled with red, as if she had been crying. But he pretended not to notice. Still, it was funny, her burning a candle so late at night when candles were so dear. And why did she look so tired and so old?

He asked no questions, however. Somehow he didn't feel as if he could say anything just then. He knew that presently his mother would come into his room to hear him say his prayers, to tuck him up in the old wool shawl and give him a last good-night kiss. Of late he had refused to say his prayers. Le bon Dieu, he thought, only bothered Himself about rich and powerful people—nobles, bishops, and such like—s what was the good of murmuring prayers that were never listened to and asking for things that were never granted? When Mother said her prayers as usual beside his bed in spite of his obstinacy, he turned his head sullenly away. He had even caught himself wishing that she would leave him alone, once he was in bed: alone, nursing his thoughts of future retribution on all those whom he hated so.

Strange that he never had the desire to talk to his mother about all that went on in his mind these days. Strange, seeing that hitherto he had always blurted out everything that troubled him, poured into her patient ear the full stories of his peccadillos, his adventures, anything and everything that passed through his mind. But now André had succeeded in persuading himself that his mother would not understand his feelings. She was, he thought, so patient and so devout that she would not sympathize with a man—a man!—who had been so deeply injured as himself. He felt that he had suddenly become a man—a man suffering an infinite wrong; and that Mother was only a woman, weak under the influence of priests and of their everlasting teachings of gentleness and humility. Men couldn't be gentle these days. They had suffered too long and too bitterly: crying wrongs, injustice that called to heaven for vengeance—only that heaven wouldn't hear. Well, if le bon Dieu wouldn't help the poor and the downtrodden to defend themselves against injustice, then they would fight on their own without help from anywhere.

Monseigneur and his sycophants! And those women with their perfumes and their silk dresses and their lorgnettes and their high-pitched voices! André hoped to God that he would live long enough to see them all eat the bread of humiliation as he himself had been forced to do.

At this point in his meditations Mother did come in. André did not hear her at first, for she had taken off her sabots and was in her stockinged feet. It was only when she stood close beside his bed that he turned his head and saw her.

Of course, he felt sorry for her. Women were women, and therefore weaker vessels, unable to take in the vast thoughts and projects of men. But they were dear gentle creatures whose ministrations were essential to the well-being of the stronger, more intellectual sex. Therefore André felt very kindly disposed towards his mother just now: he would not have admitted for the world, even to himself, that at sight of her dear old face, with its furrowed cheeks and eyes to often stern, and yet always full of love, a great yearning seized him to bury his head in her ample bosom, to forget his manhood and be a child again. However, all he said for the moment was: "Not yet in bed, Mother? Isn't it very late?"

To which she replied cheerily, "It is, my cabbage, and fully time you were asleep."

She then knelt down beside his bed. André ought then to have jumped out of bed and knelt beside her to say his prayers. This had always been the rule every since he was old enough to babble his "Gentle Jesus, meek and mild..." and clasp his baby hands; even when he began to feel himself a man, he had readily complied with the rule. But for days now, when Mother knelt beside his bed and murmured, "Our Father which art in Heaven," he had turned his head stubbornly away, nor had he looked at her till she had finished her prayers. To-night, however, though he still felt wrathful and was too big a man to get out of bed, he kept his head turned towards her so that he could see her face. There was such a bright moon outside that he could see her quite plainly: her found flat face, her thin hair already streaked with gray, parted in the middle and fastened in a small tight bun on the top of her head. Her eyes were closed while she prayed with hands tightly clasped, her lips murmuring softly, "Forgive us our trespasses"; then all at once she raised her voice and said quite loudly, "As we forgive them that trespass against us."

"I won't! I won't!" André broke in involuntarily. "I'll never forgive them, never!"

But Marianne did not seem to hear. She finished her prayers and then remained for a time on her knees, gazing on the beautiful young face that meant all the world to her. Almost distorted now with wrath and obstinacy, it was none the less beautiful; with those large dark eyes that seemed forever to be inquiring, to be groping after something unattainable. Marianne's large, capable hand wandered lovingly over the hot, moist forehead and brushed back the unruly curls which fell, rebellious, over the brow. Without another word she pressed a kiss on the eyes, closed as she thought in sleep, and on the mouth through which the young passionate breath came in slow, measured cadence. Then she tiptoed out of the room.

André was not asleep. He had felt the kiss and tasted the salt moisture of his mother's tears on his lips. For a long, long while he remained lying on his back, with widely dilated eyes staring into the darkness above him. Through the chinks in the ill-fitting door he could perceive the feeble light of the tallow candle which still burned in the adjoining room. He heard the old church clock strike one, then the half hour then two. The moon had gone, the tiny room wherein stood the boy's small plank bed was in complete darkness, save for that dim streak of light underneath the door.

As noiselessly as he could André rose and tiptoed across the room. For a few seconds he listened, his ear glued to the keyhole, but all that he could hear was an occasional sigh, and once a sound like a broken sob. The door hung loosely on its hinges, he pulled it open. His mother was still sitting sewing by the feeble candlelight. André, leaning against the door jamb, stood mutely watching her.

She seemed very busy and never looked up once in his direction. She had a pair of breeches in her hands, had evidently been at work on them. Now she fastened off the cotton, broke it off, put down her needle. André watched her. She did look old, and there was a tear which had settled on the tip of her nose. She wiped it off with her apron and then held the breeches up with both hands to see if more darning was needed. Satisfied that they were quite in order, she laid them down on the table, smoothed them out with both hands, then folded them carefully and put them to one side.

André thoughts: "Those are my breeches. She has tired herself out mending them." And the words which M. le Curé had spoken earlier in the day came hammering into his brain: "Remember, my child, that your future does not belong entirely to yourself. Your sainted mother works her fingers to the bone that you should be clothed and fed."

That was true, for there she was, working for into the night, mending his breeches, while he...

"Mother!" he said abruptly. "Do you wish me to go up to the château and see those people?"

She didn't give a start; obviously she knew that he was there. She was standing now with one hand resting on the table and peering over into the darkness to try and see him with her blinking, tired eyes.

"André! Why aren't you in bed?" she asked. "Go back at once."

"Mother!" he insisted.

"Yes, André?"

"Do you wish me to go to the château and see those people?"

"It might lead to something good for your future, my child. M. le Curé said that Monseigneur was kindly disposed."

"I have no decent clothes in which to go," the boy muttered, his sullen mood not yet quite gone.

"There are your new stockings which I have quite finished," Marianne rejoined quietly, "and I have done mending your best breeches. You can wear you father's Sunday coat and his buckled shoes—fortunately he was a small man, and you are hear as tall already."

"Mother!" André exclaimed.

"Yes, André?"

"You have been working your fingers to the bone so that I should be clothed. M. le Curé said so."

"No, my child," Marianna said, smiling through an involuntary little sigh, "not to the bone."

"And did you sit up to-night because you—you—"

"I knew that you would want your best breeches—soon."

"You knew I would change my mind and go to the château?"

"Yes, André, I knew."

"How could you know, Mother?"

"I suppose your guardian angel must have told me. He knew."

"Mother!"

This time the cry came straight from the boy's heart. With one bound he was beside his mother and with his arms was encircling her knees. His tousled head was buried in her voluminous skirt. She fell back into her chair and drew the hot, aching young head against her breast. There, resting against that warm, downy pillow, all pretence at manhood was swamped in the grief of a child. André burst into a flood of tears, the first that had welled out of the bitterness of his heart since that awful day of disgrace. Marianne, with her kind fat arms wrapped round her most precious treasure, thanked God for those tears.

The tallow candle flickered and died out. The room was in darkness, only a pale light, the first precursor of dawn, came shyly peeping presently through the small uncurtained window. The distant church clock struck four. It was more than an hour since Marianne had moved. The child had cried himself to sleep, squatting on the floor, with his head on her lap, her hand resting on his curls. From time to time a sob shook the young frame; then even the sobs were stilled, and Marianne, stiff with sitting motionless, would not move for fear of waking him.

If you should ever visit the Bourbonnais do not fail to go as far as Le Borne, on the outskirts of which stands the princely Château de marigny. It is one of the most sumptuous survivals of medieval splendour, with its unique position on a spur of the Roches du Borne, commanding a gorgeous view over the valley of the Allier with its rippling winding stream, its spreading forests of beech and walnut and sycamore, its vine-clad slopes and picturesque villages—Val-le-Roi, Le Borne, Vanzy, and so on—peeping shyly through the trees.

Originally built in the twelfth century by Jean Duke of Burgundy, it was enlarged and enriched by each of his successors, until the great Duke Charles—known to history as the Connétable de Bourbon—as great in treachery as in doughty deeds, completed the work of making the Château de Marigny second to none in grandeur and magnificence. It was to him that King Henry VIII of England referred when he remarked to François I of France on the occasion of the meeting on the Field of the Cloth of Gold: "If I had so opulent a subject, I would soon have his head off."

François I had no occasion to follow his English friend's advice, for it was soon after that that the illustrious Connétable de bourbon became a traitor to his country and sold his sword to the enemy of France, which was quite sufficient excuse for the King to declare the Duke's estates forfeit to the Crown. Some of these were subsequently sold and passed from hand to hand. The château, then known as Château de Borne, came into the possession of the Duc de Marigny, first cousin of King Henry of Navarre and a direct descendant of the Connétable who renamed it Marigny and added to his many titles that of De Borne.

Though the magnificence for which the old château was famous in the past—when 'twas said that Duke Charles kept five hundred men-at-arms within its precincts—was somewhat shorn of its dazzling rays, the present Duc de Marigny did, nevertheless, live there like a prince and entertain with lavish hospitality. These were the days, closely following on those of the Grand Monarque, when the king set the pace in splendour and prodigality and the great nobles thought it incumbent on them to emulate royal ostentation. It was the era of beautiful furniture and of exquisite silks and laces, of stately ceremonials both at court and at home, of gorgeous banquets, expensive food and wins, as well as of the aesthetic enjoyment of pictures, music, and the play. Money flowed freely into the coffers of those who had landed estates: the State favoured them, for not only were they free of taxation, but one privilege after another was conferred on them, and, quite naturally, they grasped these with both hands and then asked for more.

Cradled in the lap of luxury, wrapped up in cotton wool by sycophants and menials, they shut their eyes to the gather clouds of the inevitable Revolution. The cataclysm found them unprepared, scared, and astonished, like children wakened out of a dream. Most of them had not done blinking their eyes under the shadow of the guillotine. When they died, they died like heroes. They would have lived like heroes had they been given the lead, had they understood that the distant thunder of growing discontent among the people, the flashed of lightning of menace and revenge, were the precursors of a raging storm that threatened them, their traditions and their caste.

In this year of grace 1782 Monseigneur le Duc de Marigny, one of the richest and most distinguished memebers of the old French aristocracy, connected with the royal houses of Bourbon and Orléans, was certainly one of those who thought that most things were for the best in this best possible world. The only thing that ever troubled him was the occasional tightness of money. This was an unheard-of thing. The Duc de Marigny, cousin of kinds, short of money! in his father's day, my gad, sir! if there were no Jews to skin there were always those lazy, good-for-nothing peasants whose whole excuse for being alive at all was that they should provide their seigneur with everything he was pleased to want.

Those were the good old days. Now there was nothing but grumbling in the villages. Bad weather, poor harvest, bad luck. Eh, morbleu! Monseigneur knew well enough that the harvests were poor. If they weren't, he wouldn't be so terribly short of money; just when Aurore's birthday was coming on, too, and the château was going to be full of the most distinguished visitors that he had ever assembled under one roof. He was an amiable old gentleman, this descendant of the great Connétable: he did not aspire to have five hundred men-at-arms under his orders, but he did expect his house to be second to none in the matter of hospitality and of splendour. And Aurore meant half the world to him. He had been married three times: the first two duchesses had failed in their duty of presenting him with an heir, the third one turned her face to the wall and died when a tiny baby girl was first put against her breast. Monseigneur quickly consoled himself and would no doubt have brought a fourth duchess home to grace the head of the table only that his reputation of Bluebeard had made the eligible young ladies of his own rank chary of accepting so dangerous a position. Moreover, little tiny Aurore had already entwined himself around his fickle old heart. He forswore the delights of matrimony for the more durable ones of fatherhood, and devoted all the time that he could spare from the study of his own comforts to the furtherance of Aurore's enjoyment of life.

It is, perhaps, a little difficult to imagine a girl in her teens taking pleasure in games and pursuits which in these modern days would rouse the scorn of a child of seven—difficult to visualize that bright sunny day in July, 1782, when Aurore's birthday party, consisting of twenty or thirty of her friends in ages ranging from thirteen to twenty-three, spent their afternoon in playing blindman's bluff or hide-and-seek in the terraced gardens of Marigny. In and out the bosquest and parterres they darted like so many gaily plumaged birds, filling the air with their laughter and childish screams of delight, the while Monseigneur le Duc in his boudoir was giving M. Talon, his bailiff, a bad quarter of an hour.

"Mort de Dieu! you old muckworm!" was one of the many pleasant ways in which Monseigneur addressed the unfortunate Talon. "Have I not told you that I must have five thousand louis before the end of the month?"

"Yes, monseigneur," Talon replied obsequiously, "but—"

"There is no 'but' about it, my man, when I said 'must'—" Monseigneur broke in drily.

"The tallage has all been paid—the salt tax, the window tax—"

"Call it the harvest tax or any cursed name you choose, but find me the money, or else—"

"Monseigneur!" protested Talon, who was quaking in his buckled shoes, knowing well enough what menace was being held over his head.

"Or else," Monseigneur went on slowly, emphasizing his words, "you and your precious family quit my service; I have no use for incompetent menials."

"Monseigneur!" Talon protested again, and with hands upraised called Heaven to witness his loyalty and his competence.

"Ed, what? There is no 'monseigneur' about it; and your sanctimonious airs, mon ami, are no use to me. I have thirty guests in the house; it is Mademoiselle's birthday. I have told you that before, have I not?"

"As if I could forget—"

"Very well, then. Even with your limited intelligence you must be aware that in order to entertain such distinguished persons I must have my larder and my cellars full. Well! I'm short of wine. You know that. You know that we sent to that thief in Nevers for some, and that the mudlark refuses to send the wine unless he is paid beforehand."

"I know that, monseigneur."

"You also know that I am giving Mademoiselle a ruby necklace for her birthday. You wrote the order out yourself."

"Yes, monseigneur."

"Well, then! that also has to be paid for," Monseigneur concluded with what he felt was unanswerable logic. "So do not dare to appear before me again without at least—mind! I say at least—five thousand louis in your filthy hand. Now you can go."

Talon's narrow hatchet face, usually sallow and bilious, took on an ashen hue. Through narrow deep-set eyes he cast a furtive glance at his irascible master. But Monseigneur, having delivered his ultimatum, no longer troubled his august head about his unfortunate bailiff. No doubt experience had taught him that under threat of dismissal Talon had always contrived somehow to produce the necessary money. Monseigneur never troubled his head much whence that money came. He had never been taught to troubled his head about anything so mean and sordid as money. He paid Talon a liberal salary, gave him a good house, productive land, and every facility to rob and cheat him, in order that this man should take all such burdens to enjoy life without care or worry. Many a time had Talon heard this philosophy propounded to him by his master: he knew that argument and protests were worse than useless, and it is to be supposed that in an emergency like the present one it was safer to incur further hatred from Monseigneur's tenants than the displeasure of Monseigneur himself.

M. le Duc for the moment appeared to have forgotten Hector Talon's very existence; he had caught sight through the wide-open window of his darling little Aurore at play with her friends. There was a grand game of blindman's bluff going on, and the sight would have gladdened any old man's heart, let alone that of a doting father. Monseigneur's eyes gleamed with pleasure; the misfortune of "blindman" who measured his length on the sanded path drew a delighted roar of laughter from him. Talon thought and hoped that he was momentarily forgotten and that he could achieve his exit without hearing further abuse or further threats. As noiselessly as he could he turned on his heel and made for the door. Just as he was about to slip through it Monseigneur's pleasant voice once more reached his ear:

"That reminds me, Talon," he said lightly, "that my cousin M. le Marquis d'Epinay had a splendid idea last year when he was short of money. There was all that stony land on Mont Oderic and Mont Socride, you remember? It was no use to him, he couldn't make anything out of it. So he made the neighbouring communes buy it of him at his own price. I believe the rascals have done very well with it since. Well! there's that bit of land the other side of Rocher Vert. I don't want it. Let the communes of Val-le-Roi and Le Borne buy it of me. They can have it for three thousand louis and you can make up the other two out of the hoard which you have amassed through robbing me, you black-guard."

"The communes couldn't pay, monseigneur," Talon protested, and then added very injudiciously: "As for me, how can Monseigneur think—"

"That you are a thief and a liar?" Monseigneur broke in, with a careless laugh. "Why, you villain, if you were a decent man you would have left my service long ago. You know that I only employ you to do my dirty work, which I couldn't ask others who are clean and honest to do for me. As for the communes, what I propose is a sound bargain for them: those peasants can make a good thing out of land, which you are too big a fool to turn to account. Anyway, that's my last word, and now, get out of my sight. I am sick of you."

Talon was as thankful to go as Monseigneur was to be rid of him. He slipped like a stealthy cat through the door, while Monseirgneur, throwing cares and money worries off his broad shoulders, returned to the more agreeable occupation of watched his daughter playing at blindman's bluff.

Perhaps, if he had been gifted with second sight, M. le Duc de Marigny would not have felt quite so carefree: for then he would have seen his bailiff, Hector Talon, the other side of the door, pausing for a moment with clawlike fingers resting on the handle. On his sallow face there was neither humility nor servility, only a cunning, mocking glance in the narrow, deep-set eyes and a sneer upon the pale thin lips. What went on in the man's mind it is impossible to say. Did he long to turn on the hand that fed him? Did he foresee that, on a day not very far distant, he would be the one to command and Monseigneur the dependent on his good-will? All unconsciously now, even good-humouredly, Monseigneur chose to snub and humiliate him. There was no conscious feeling of arrogance in so great a gentleman's treatment of his subordinates; just the belief amounting to a certainty that he and his kind were made of a different clay from the rest of humanity, and that God had preordained them to rule and the others to obey. All these thoughts and hopes did, no doubt, course through Hector Talon's mind as he stood on the other side of the door with his fingers on the handle. But Monseigneur knew nothing of that. He was not gifted with second sight and did not see the change of expression in his bailiff's face—just as he had only given one casual and careless glance at the boy at the whipping post whom the ladies had so aptly named "the rebel angel."

On this same afternoon when André Vallon, still rebellious in spirit, followed M. le Curé de Val-le-Roi up the wooded slopes that led to the château, the picture that was revealed to his gaze when he came in sight of the gorgeous old building, with its sumptuous gardens, its marble terraces, its towers and battlements, its stately trees and wealth of flowers, was one he never forgot. Vagually he had heard the château spoken of by those who knew, as "magnificent"; vaguely he was aware that Monseigneur lived there in a state of splendour of which he, a village lad, had no conception, even in his dreams; and from the valley below, where on the outskirts of Val-le-Roi his mother's cottage lay perdu, he had often gazed upwards to the heights, where at sunset the pointed roofs glistened like silver and the rows of windows sparkled like a chain of rubies; but he had never been allowed to wander up the slope and see all that magnificence at close quarters.

Heavy gilded iron gates shut off the precincts of the château from prying eyes and vagabond footsteps; stern janitors warned trespassers against daring to set foot inside the park; and thus the place where dwelt those unapproachable personages, Monseigneur and his friends, had hitherto appeared to André like fairyland, or rather, like the ogre's castle of which he had read in the storybooks of M. Perrault—the ogre who devoured all the good things of this earth and always wanted more.

André was dazzled. The same enthusiasm that made him love the moonlight, the cottontails, or the hedgerows caused him to utter a cry of pleasure when he first caught sight of the château. He came to a halt and allowed his eyes to feast themselves on the picture. M. le Curé was delighted; he thought that the boy was showing a nice spirit of reverence and of awe.

"It is beautiful, is it not, André?" he remarked complacently.

But André's mood was not quite as serene as the worthy priest had fondly hoped. He turned sharply on his heel and retorted with a scowl:

"Of course it is beautiful, but why should it be his?"

"What in the world do you mean?"

"You call that man up there 'Monseigneur.' Why? This all belongs to him. Why?"

"Because..."

The good Curé droned on. André certainly did not listen; he stalked on once more, irritable and silent. He had asked a question for which, in his own mind, there could not possibly be an answer. True that something of the bitterness of intense hatred had, as it were, flowed out of him with the tears which he had shed on his mother's breast, but the spirit of inquiry, of blind groping after mysteries which were incapable of solution had, for good or ill, replaced the childish acceptance of things as they were. To him henceforth his mother's penury and Monseigneur's wealth were not preordained by God; they did not form a part of the scheme of creation as God had originally decreed. They were the result of man's incapacity to grapple with injustice; the result, in fact, of the weakness of one section of humanity and of the arrogant strength of the other.

Very wisely, M. le Curé had not pursued the contentious subject. Together the two of them found their way across the wide, paved forecourt and up the perron. Lackeys in gorgeous liveries opened wide the gates of the château, and André, feeling now as if he were in a dream, silent, subdued, all the starch taken out of him, all the rebellion of his spirit overawed by so much splendour, kept close to the Curé's heels.

They went through the endless rooms, across floors that were so slippery that André, in his thick shoes, nearly measured his length on them more than once. He caught sight of himself in tall mirrors, full face, sideways, walking, sliding, pausing, wide-eyed and scared, thinking that the figure he was coming towards him was some strange boy whom he had never seen before. At length the Curé came to a halt in what seemed to André like a fairy's dwelling place, all azure and gold and crystal, where more tall mirrors reflected a somewhat corpulent old man in a long black soutane, and a tall, clumsy-looking boy in an ill-fitting coat, with tousled hair and large hands and feet encased in huge, thick buckled shoes.

On one side of the room there were three tall windows through which André saw such pictures as he had never seen before. At first he didn't think that they were real. There were marble balustrades and pillars, parterrers of flowers and groups of trees, and a fountain from whose sparkling waters the warm sunshine drew innumerable diamonds. This fairy garden appeared peopled with a whole bevy of brightly plumaged birds that darted in and out among the bosquets and the parterres with flutelike calls and rippling music. At least, so it seemed to André at first. M. le Curé, tired out, hot and panting, had sunk down in one of the gilded chairs and was mopping his streaming face; André, attracted and intrigued by the picture of that garden and those birds, ventured to go nearer to one of the tall windows in order to have a closer look. The window was wide open. André, leaning against the frame, stood quite still and watched.

A merry throng peopled the garden; ladies in light summer dresses, some with large straw hats over their powdered hair, others with fair or dark curls fluttering about their heads, men in silk embroidered coats, with dainty buckled shoes and filmy lace at throat and wrist, were chasing one another in and out of the leafy bosquets, just like a lot of children, playing some puerile game of blindman's bluff, which elicited many a little cry of mock alarm and silvery peals of merry laughter. How gay they seemed! How happy! André watched them, fascinated. He followed the various incidents of the game with eyes that soon lost their abstraction and sparkled with responsive delight. He nearly laughed aloud when an elegant gentleman in plum-coloured satin cloth, his eyes bandaged, tripped over a chair mischievously placed in his way by one of the ladies—a girl whose pink silk panniers over a short skirt of delicate green brocade made her look like a rosebud: so, at least, thought André.

He quite forgot himself while he stood and watched. Like a child at a show, he laughed when they laughed, gasped when capture was imminent, rejoiced when a narrow escape was successful. M. le Curé, overcome by the heat, had gone fast asleep in his chair.

André, absorbed in watching, did not even notice that the crowd of merrymakers had invaded the terrace immediately in front of the window against which he stood. "Blindman" now was the young girl with the fair hair, free from powder, whose dress made her look like a rosebud. With arms outstretched she groped, after the clumsy fashion peculiar to a genuine blindman, and her playmates darted around her, giving her a little push here, another there, all of them unheedful of the silent, motionless watcher by the open window. And suddenly "Blindman," still with arms outstretched, lost her bearings, tripped against the narrow window sill and wound have fallen headlong into the room had not André instinctively put out his arms. She fell, laughing, panting, and with a little cry of alarm, straight into him.

There was a sudden gasp of surprise on the part of the others, a second or two of silence, and then a loud and prolonged outburst of laughter. André held on with both arms. Never in his life had he felt anything as sweet, as fragrant, so close to him. The most delicious odour of roses and violets came to his nostrils, while the downiest, softest little curls tickled his nose and lips. As to moving, he could not have stirred a muscle had his life depended on it.

But at the prolonged laughter of her friends the girl at once began to struggle; also, she felt the rough cloth beneath her touch, while to her delicate nostrils there came, instead of the sweet perfumes that always pervaded the clothes of her friends, a scent of earth and hay and of damp cloth. She wanted to snatch away the bandage from her eyes, but strong, muscular arms were round her shoulders, and she could not move.

"Let me go!" she called out. "Let me go! Who is it? Madeleine—Edith, who is it?"

The next moment a firm step resounded on the marble floor of the terrace, a peremptory voice called out: "You young muckworm, how dare you?" and the hold round her shoulders relaxed. André received a resounding smack on the side the face, while the girl, suddenly freed, staggered slightly backward even while she snatched the handkerchief from her eyes.

The first thing she saw was a dark young face with a heavy chestnut curl falling over a frowning brow, a pair of eyes dark as aloes flashing with hatred and rage. She heard the voice of her cousin, the Comte de Mauléon, saying hoarsely:

"Get out! Get out, I say!" And then calling louder still: "Here! Léon! Henri! Some of you kick this garbage out."

It was all terrible. The ladies crowded round her and helped to put her pretty dress straight again, but the girl was too frightened to think of them or her clothes. Why she should have been frightened she didn't know, for Aurore de Marigny had never been frightened in her life before: she was a fearless little rider and a regular tomboy at climbing or getting into dangerous scrapes; but there was something in that motionless figure in the rough clothes, in those flashing eyes and hard, set mouth which puzzled the child and terrified her. Here was something that she had never met before, something that seemed to emit evil, cruelty, hatred, none of his had ever come within sight of her sheltered, happy life.

Pierre de Mauléon was obviously in a fury and kept calling for the lackeys, who, fortunately, were not within hearing, for heaven alone knew what would happen if anyone dared lay hands on that incarnation of fury. The boy—Aurore saw that he was only a boy, not much older than herself—looked now like a fierce animal making ready for a spring; he had thrust one hand into his breeches' pocket and brought out a knife—a miserable, futile kind of pocketknife, but still a knife; and his teeth—sharp and white as those of a young wolf—were drawing blood out of his full red lips.

Some of the laidies screamed; others giggled nervously. The men laughed, but no one thought of interfering. Inside the room, M. le Curé, roused from his slumbers, had obviously not yet made up his mind whether he was awake or dreaming.

Just then the two lackeys, Léon and Henri, came hurrying along the terrace. A catastrophe appeared imminent, for the boy had seen them; knew, probably, what it would mean to him and all these bedizened puppets if those men dared to touch him. He was seeing red; for the first time in his life he felt the desire to see a human creature's blood. With jerky movements he grasped the flimsy, gimcrack pocketknife with which he meant to defend himself to the death. He met the girl's eyes with their frightened, half-shy glance and exulted in the thought that in a few seconds, perhaps, she would see one of her lackeys lying dead at her feet.

Not even on that fatal day when he had tasted the very dregs of humiliation had his young soul been such a complete prey to rebellion and hatred. Why, oh, why had he allowed his heart to melt at sight of his mother's wretchedness? Why had he ever set foot across this cursed threshold? Pay! Pay! Pay! Those were once his mother's words. Pay, while these marionettes laughed and played; pay, so that their bellies might be full, their pillows downy, their hair powdered and perfumed. He hated them all. Oh, how he hated them!

These riotous thoughts were tumbling about in André's brain, chasing one another with lightning speed while he was contemplating murder and hurling defiant glances at the pretty child, the cause of this new—this terrible catastrophe.

Ever afterwards he was ready to swear that not by a quiver of an eyelid had he betrayed fear or asked for protection. Asked? Heaveans above! He would sooner have fallen dead across this window sill than have asked help from any of these gaudy nincompoops.

Be that as it may, there is no doubt that it was the girl's piping, childish voice which broke the uncomfortable spell that had fallen over the entire lively throng.

"Ohé!" she cried, with a ripple of laughter. "How solemn you all look! Pierre, it is your turn. Come, Véronique, you hold him while I do the blindfolding; don't let him go—it is his turn."

Her friend to whom she called was close by and ready enough to resume the game. Before Pierre de Mauléon had the chance to resist she had him by the hand, while Aurore tied the handkerchief over his eyes. A scream of delight went up all round. All seriousness, puzzlement, was forgotten. Pierre tried to snatch the handkerchief away, but two of them held onto his hands; the others pushed and pinched and teased. They dragged him along the terrace; they vaulted over the marble balusters; they were children, in fact, once more, tomboys, madcaps, running about among the bosquets and the flowers, irresponsible and irrepressed, while André, without another word, another look, turned on his heel and fled out of this cursed château, leaving M. le Curé to call and to gasp and to explain to Monseigneur, as best he could, what, in point of fact, had actually happened.

There are several biographies extant of André Vallon, some written by friends, others by enemies. No man who has played a rôle on the world stage has ever been without his detractors, and only a few have been without their apologists. To have really complete conception of Vallon's temperament, character, and subsequent conduct, it would be necessary to know something of his life during the ten years that followed.

He was little more than fifteen when he left his village of Val-le-Roi and went up to Paris under the aegis of M. l'Abbé de Rosemonde, who had obtained for him, after much tribulation, countless petitions, and untiring zeal, a scholarship in the College of the Oratorians in Paris, where a few years before this a young scholar named Georges Danton had pegged away at the classics, and where many young minds began nursing those thoughts of rebellion and agitation which were to render them famous or infamous in the annals of the greatest revolution of all time.

Some of these men, at the time that André Vallon went to the Oratorians, were already prominent in the public eye. Danton at this date was Conseiller du Roi, was calling himself Maître d'Anton and had a fine practice and a pretty young wife. Maximilien de Robespierre had finished his studies at the Collège Louis-le-Grand and was now a leading light of advocacy; and Camille Desmoulins was a notorious journalist. André, who had developed a hitherto latent ambition, and with such examples before him of success won by hard work, became as model a scholar as he had been a turbulent village lad. That it took all M. le Curé's eloquence and floods of his mother's tears to persuade him to go to college at all goes without saying, but he did go in the end.

How much it cost his mother to keep him in decent clothes while he was at college remained forever a secret within her ample bosom. As André grew to be a man he made a pretty shrewd guess at the hardships which she must have endured in order to put by a few louis every year so that he should not cut too sorry a figure among his schoolfellows. Luckily for him, he never felt any sense of humiliation at his own shabby clothes or want of money to spend. He was so firmly persuaded that his mother's poverty and his own empty pockets were only transitory states which would be remedied by himself when he was a man. And then, again, some of those whose names at this hour were on everybody's lips had been as poor as himself. Camille Desmoulins never had a sou from his avaricious father to spend on leasure or finery, and Robespierre's clothes were invariably threadbare.

Moreover, as the years went on, poverty became so much a matter of course, except in the case of a privileged or a dishonest few, that it ceased to have any significance. It was a matter of caste, that was all, and became such an accepted fact that for a family man not to be hungry, to have fuel on his hearth or shoes on his feet was to be something of an alien among his own class. Nor was it shame that stirred André's young blood to boiling when he saw his mother in her old age, still scrubbing floors or toiling up to the château to do the family washing; it was only passionate rage at his own impotence to drag her out of her penury, and ever growing better resentment at a social system which permitted the few to have all the good things of this world and allowed the many to go under for want of sufficient nourishment. That this resentment should lead a young mind to wholesale condemnation of the present régime was only natural, seeing that the King was an autocratic monarch, and that his word, and his word alone, made and unmade the laws.

In 1788 André Vallon was called to the bar and delivered, as was customary, his diploma speech in Latin. The subject set for the year was the social and political condition of the country and its relation to the administration of justice. A ponderous subject for a village lad to tackle, but even Vallon's detractors—and he already had a few—were ready to admit that he acquitted himself adequately, and that his Latin was faultless. The grave and reverend seigneurs of the law, on the other hand, sat up in amazement and rubbed their lack-lustre eyes when they heard this young advocate from the back of the provincial beyond spout grandiloquent phrases, such as Salus populi suprema lex esto, and with wide gestures of delicately modelled hands strike a note of warning to those in high places—to all who had inherited power, influence, or riches.

"Qui habet aures auriendi," he thundered. "Audiat."

There could be no two opinions about it: it was an incendiary speech, even though there were no actual words in it that could be construed into excitation to reprisals or insurrection. On the contrary, it even concluded with a passionate appeal to those who had the ear of the malcontents to pause before they led the people blindly along the paths that led to revolution.

"Woe to him," he fulminated in conclusion, "who for his own advancement plays on the passions and the prejudices of the people. Woe to the instigator and the maker of revolutions!"

Thus ended his impassioned harangue, delivered in the language of Ovid and Virgil, leaving his learned audience marvelling at this young Cicero sprung out of a remote village, and gravely shaking their heads at the unorthodox sentiments to which they had been compelled to listen.

A week later André was at home, telling his mother all about it, courting her approval more ardently than he had done that of the leading lights at the Paris bar. There was something in Marianne Vallon's calm philosophy, in her acceptance of the inevitable, which by its very contrast appealed to André's rebellious spirit.

"You help me to keep my balance, Mother," he would say with all youth's impatience, when she talked as she often used to do in the past, of resignation and humility. "And God knows we shall all of us want it presently," he added, with a careless shrug and a laugh.

He went through all the fatigue of translating his Latin speech into French for her, so that she might understand and criticize. But he was quite proud of his achievement; he knew that he had left his mark on the somewhat somnolent brains of his fellow advocates.