|

Project Gutenberg

Australia a treasure-trove of literature treasure found hidden with no evidence of ownership |

BROWSE the site for other works by this author (and our other authors) or SEARCH the entire site with Google Site Search |

Title: Collected Short Stories, Vol. X Author: Fred M. White * A Project Gutenberg of Australia eBook * eBook No.: 1301031h.html Language: English Date first posted: Mar 2013 Most recent update: Mar 2013 This eBook was produced by: Roy Glashan Project Gutenberg of Australia eBooks are created from printed editions which are in the public domain in Australia, unless a copyright notice is included. We do NOT keep any eBooks in compliance with a particular paper edition. Copyright laws are changing all over the world. Be sure to check the copyright laws for your country before downloading or redistributing this file. This eBook is made available at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg of Australia License which may be viewed online at http://gutenberg.net.au/licence.html To contact Project Gutenberg of Australia go to http://gutenberg.net.au

GO TO Project Gutenberg Australia HOME PAGE

APART from numerous novels, most of which are accessible on-line at Project Gutenberg Australia and Roy Glashan's Library, Fred M. White published some 300 short stories. Many of these were written in the form of series about the same character or group of characters. PGA/RGL has already published e-book editions of those series currently available in digital form.

The present 17-volume edition of e-books is the first attempt to offer the reader a more-or-less comprehensive collection of Fred M. White's other short stories. These were harvested from a wide range of Internet resources and have already been published individually at Project Gutenberg Australia, in many cases with digitally-enhanced illustrations from the original medium of publication.

From the bibliographic information preceding each story, the reader will notice that many of them were extracted from newspapers published in Australia and New Zealand. Credit for preparing e-texts of these and numerous other stories included in this collection goes to Lyn and Maurie Mulcahy, who contributed them to PGA in the course of a long and on-going collaboration.

The stories included in the present collection are presented chronologically according to the publication date of the medium from which they were extracted. Since the stories from Australia and New Zealand presumably made their first appearance in British or American periodicals, the order in which they are given here does not correspond to the actual order of first publication.

This collection contains some 170 stories, but a lot more of Fred M. White's short fiction was still unobtainable at the time of compilation (March 2013). Information about the "missing stories" is given in a bibliographic note at the end of this volume. Perhaps they can be included in supplemental volumes at a later date.

Good reading!

CHRIS HAMMOND stood before his study fire, his head erect, for he had found the way out, and the credit of the firm was saved. He was like the man who slipped down the mountain crevasse to find himself face to face with a slow and lingering death. There had only been one way out, and that by means of a stream appeared to run into the very heart of the mountain. And the man who had fallen knew that the stream had to emerge into a valley somewhere, and, taking his courage in both hands, he had dived for it. So Chris Hammond had dived for it. The odds on tragedy were long, but he had come up at length in the smiling valley, spent and exhausted and at the last gasp.

Hammond has taken this risk financially, and at the eleventh hour relief had come. If he could get over to Sedgley before the bank opened in the morning, the men would be paid, and all the ominous rumours silenced. Once the week-end was passed, then all was smooth as far as the future was concerned. The money for the American contracts was due on Wednesday, and after that date Hammond would see the open sea.

He had the money there in his safe in gold, for it was useless to expect the bank people at Sedgely to honour a cheque. There were two thousand hands at the Sedgely works, and three hours ago it was odds against them getting their week's wages--in other words Hammond & Son were of the verge of suspending payment. Usually Hammond himself went over to Sedgely in his car with the weekly money. Sometimes it took the form of a cheque, but latterly there had been trouble with the bank and gold had been necessary. There were other creditors who insisted on being paid in cash, too, and one of them would be waiting at the works by appointment as soon as the doors were open. And this man must not be disappointed. It would he far better to run over in the car there and then, and get Martin, the manager, to place the money in the office safe.

"Isn't it rather a risk?" Mrs. Hammond asked. "These things get talked about. And I don't like the idea of you taking that lonely road with all that money upon you."

Hammond laughed at his wife's fears.

"Fancy you talking like this," he said. "What would your people say if they heard a Ravoli talking in this fashion?"

Mrs. Hammond laughed, though her clear olive skin was faintly tinged with red. She was very small and very dark, with a suggestion of the East in her black eyes. Nobody knew exactly where Sheila Hammond had come from, and people were content to believe that Hammond had found her during his mining experiences in Eastern Europe. There was an certain suggestion of the gipsy about her--she had it in her lithe and graceful walk, she had a phenomenal hearing, and her knowledge of the ways and moods of Nature was amazing. But if she had been a daughter of the wild, the ways and manners of civilisation had come to her gracefully and naturally. She sat there now, coiled up in a big armchair before the fire, her eyes gleaming as brightly as the tiny diamonds in her ears.

"Don't you see, I must go," Hammond said. said. "The credit of the firm is saved. We We shall get over Terry's defalcations now. Once confidence is restored, the rest is easy. I dare not wait till to-morrow. If anything happened to me in the meantime,the hands at Sedgley would not be paid, and you know what that means."

Mrs. Hammond raised no further protest. Hammond kept no chauffeur now, and, indeed, his car was perfectly safe in his confident hands, and just now every expense had to be considered. He was rather looking forward to his trip across the twenty miles of lonely heath and moorland which lay between his house and Sedgely. It was not a bad road; the night was clear, with a moon riding high in the sky, as he set himself going. With any luck, he would he back by midnight.

There were no police traps in these parts, so that he set the car in motion, rising higher and higher till the whole of the country opened out before him. There were certain portions of the road cut between overhanging cliffs, and it was at the foot of one of them that Hammond pulled up his ear with a jerk. Half a dozen big boulders lay right across the track. Probably, there had been a bit of a landslide, for these things did happen sometimes. They were big and heavy stones, and would take a bit of moving even for a strong man like Hammond, But there was no help for it--it was useless to waste his time cursing his unlucky fate. He got out of the car, throwing aside his coat and vest, and went to it with a will. He had scarcely stooped down to the first boulder, when a figure arose from the roadside and barred his way. Almost unconsciously, Hammond's hand went to his hip-pocket. He scented danger as a wolf scents is prey. But there was no revolver in his pocket, for that was in the car under the seat.

The man opposite grinned in sinister fashion. He was dark and swarthy, a mass of black hair was matted on his head, and Hammond could see that there were rings in his ears. Evidently the fellow belonged to some wandering gipsy tribe which passed the summer on the moorlands, living in some mysterious and devious fashion, a pest to the countryside and the inveterate foe of every gamekeeper for miles around.

"Did you put those stones there?" Hammond demanded.

"I did," the man replied promptly-- "at least, I and my mates did between us. You're Mister Hammond, aren't you?"

"At your service," Hammond said grimly.

"Well, I don't mind saying that we've been waiting for you. You may just as well take it quietly, We don't want to hurt you, if we can help it. It's the money we're after."

"Oh, indeed! And you expect to get it?"

The man showed his teeth in an evil grin.

"We've been waiting for this chance for weeks," he said. "You're going over to Sedgely, and you've got over four thousand pounds in gold in the car. It was brought over from Westerham by special messenger, and reached your house just before dinner-time to-night. Question is, are you going to take it quietly, or shall we have to use force?"

Hammond bent down and rolled one of the stones away. He was thinking furiously. What a fool he had been to come here all alone like this! He could easily have got one of his friends to accompany him. One man of pluck now with a revolver in his hand would have been worth the credit of Hammond's firm. If he yielded to threats, ruin stared him in the face. Almost better death than a disaster like that. He might he lucky enough to get these big boulders out of the way, and, once the road was clear and Fate was kind, he might make a dash for it. The engine was still running, the money was in the car, and, so far as he could see for the moment, he had only one antagonist to deal with. The man set on the roadside watching Hammond until the last of the obstacles were cleared away. He could see that Hammond's hands were cut, he could see the perspiration rolling down his face.

"What are you going to gain by that?" he scoffed. "Come on, Mister Hammond, the game's up!"

"I'm glad you think so," Hammond said between his teeth. "Do you suppose I've got the money in my pocket?"

"No, but it's in the car, mister. You stay here while I go and find it. In little leather bag, isn't it?"

The road was clear now, at any rate. Hammond made s dash for the car and laid his hand on the brake. He felt a grip upon his shoulder. In a blind rage he rose to his feet and struck out right an left. The gipsy clinched, and together the pair rolled ever into the road, struggling and snarling like dogs. The gipsy was antagonist fit enough for any athlete to tackle, but Hammond was fighting with the courage of despair, fighting for his home and his honour an his reputation. He shook off the other's grip and flung him violently on the roadside. He turned to the car again, filled with a wild exultation and the joy of victory. If he could once get the car moving, he was safe.

Then another figure seemed to emerge from the shadows, something gleamed in the moonlight, and Hammond rolled over in the road, absolutely lost to his surroundings.

He opened his eyes again presently, wondering where he was and what had happened. His head was racked with pain, earth and sky and moon reeled before his eyes in one wild panorama. What was he doing there, and what was that warm fluid trickling down the back of his neck? And who were all these people, and where did they come from? Somebody was shouting something shrilly, but really nothing mattered just at that moment. All Hammond wanted to do was to go to sleep and forgot all about it, But gradually, in spite of the racking pain things became more clear. Hammond found himself kneeling in the middle of the road by the side of the car. He saw, almost subconsciously that the locker under the seat was still intact. Up to now, at any rate, these ruffians had not succeeded in their errand.

Somebody was standing behind Hammond, issuing orders in a shrill, childish voice. Opposite her, a few yards up the road, were three men and a woman. Hammond recognised his late antagonist by the rings in his ears, which was his only method of identification, for the three men were wonderfully alike, and, indeed, the woman might been a fourth man but for her clothing. They danced and gesticulated wildly. They seemed to be beside themselves with impotent fury. They were hurling torrents of execrations in some lurid foreign tongue at someone who appeared to be behind Hammond's shoulder. He was getting a proper grasp of the situation now. He looked eagerly behind him. And there, as a terrier might stand guard over here young, was a tall slip of a girl with a mass of black hair streaming wildly over her shoulders. She was dressed in a red blouse and skirt, which served to render her picturesque beauty still more striking. Her slim legs were bare, and in her hands she was holding a gun. She was handling it, too, quite after the manner of a master. I was a poacher's gun with a short barrel, the type of weapon that Hammond had seen a score of time. A similar gun lay at her feet, loaded and capped, as Hammond did not fail to note.

"What's the meaning of all this?" he asked

"Oh, don't you worry, mister," the girl said. "I hear what they were saying last night. If they hadn't have found it out, I should have come and warned you. But, they tied my hands and feet and kept me in one of the tents. I managed to get away just in time. Then I came here with the guns, and--well, that's all about it. And if they dare lay hands on you again, I'll shoot! Yes, I will, if they cut the life out of me!"

"You're a plucky girl," Hammond said admiringly. "But why should you take all this trouble for me?"

"Ask Sheila," the girl said simply.

Hammond begun to wonder if he was dreaming again. But that fine, lively pain at the back of his brain was took keen for that. But what on earth could this ragged wayside waif know of his wife? Why should she speak of her in this familiar fashion? Still, the danger was too acute and vivid for the wasting of time on problems like these. There were three desperate men in front, ready for anything, not even short of murder, now that their batteries were unmasked, and others might come up at any moment. Hammond did not fail to grasp the situation. These people would kill him now if they got the chance. They would probably kill the girl, too. Once that was done, and the car got out of the way, the tragedy might remain a mystery for all time. More than one man knew that the firm stood on the verge of ruin, and they would assume, naturally enough, that Chris Hammond had fled abroad with all the money he could scrape together, rather than face his creditors. Probably no search would even be made for him. And here he was, on a lonely road, ten miles from anywhere, with nothing between him and certain death beyond a slip of a girl with two charges in a pair of ancient shot-guns.

"I'm sorry you took this risk," Hammond said. "It doesn't so much matter about myself--I've faced death too often to be afraid of it--but you are over-young to die."

"I did it for Sheila," the girl said.

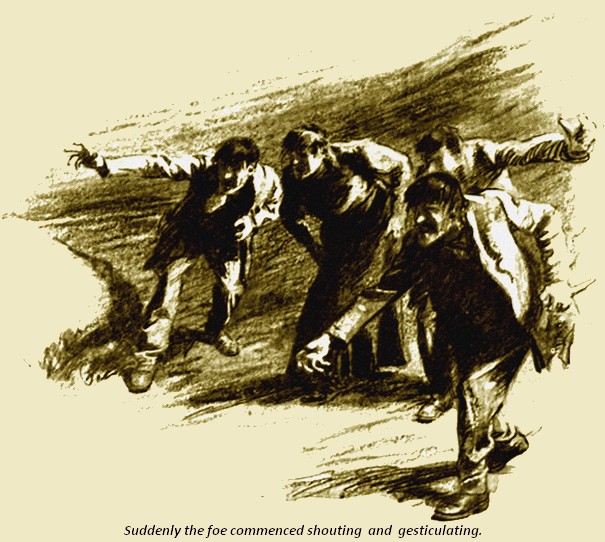

It was very strange to hear this out in the open country, face to face with a terrible peril--to hear the girl speak as if she and Sheila were lifelong friends. The jabbering and gesticulating down the road had ceased for a moment, and it was evident that the ruffians were planning some new method of attack. It was fortunate, perhaps, that they could only advance towards the car, for the high cliffs on both sides prevented any onslaught from the rear. Suddenly the foe commenced shouting and gesticulating; then they came with a swift dash. Hammond struggled to his feet and reached down for the other gun. He saw the girl's weapon go like a flash to her shoulder, there was a loud report, and one of the men dropped by the way, his right arm hanging helplessly by his side. It was all bravely and magnificently done, but Hammond did not fail to realise the fact that only one shot remained now between himself and a certainty of absolute defeat.

"That was bravely and magnificently done," he said. "But we shall have to be careful. I ought to have a revolver somewhere in the car. Once I can show them that, we shall be free. I suppose you can keep them off a few minutes longer."

The girl showed her teeth in a flashing smile.

"They won't want any more for a bit," she said. "Better get your revolver."

Hammond came back from the car white and savage. The revolver was not there. It might have been snatched from its place when he was lying unconscious in the road, or it might have been stolen earlier in the day. As these people had laid their plans so carefully, the latter was more probable. Anyway, the fact remained that the weapon was gone, and the situation stood unchanged. Hammond caught his teeth between his lips. He was savagely set upon getting away now. Dimly he began to see an avenue of escape opening out before him.

"Jump in the car," he whispered. "Jump in, and I'll set her going. We'll make a dash and go clean through them."

He did not wait to see whether his companion obeyed him or not. That she was behind him he took for granted. Then the car gathered way, until Hammond was nearly over the men who barred his progress. The ear swayed perilously to one side of the road, and a second later the danger was past. But Hammond's triumph was short-lived. He glanced over his shoulder, to find that the girl was not there. He heard a report and saw the flash of a gun; then in the moonlight he could make out the figure of the girl dashing at full speed across the moor. He could also see two figures in hot pursuit.

"I can't leave her like that," he told himself. "Dash it all, I should be little less than a murderer if I did! Here goes, whatever the consequence is!"

He steered the car across the moorland, praying that nothing might happen to check him now. The car bumped and thrashed over the heather. The girl was getting nearer and nearer now. There was just time to pull up as she passed, and lift her, panting and breathless, into the seat by Hammond's side. She lay almost unconscious, with her eyes closed, whilst Hammond carefully picked his way back to the high-road again. The danger was past and done now, the figures of the gipsies had receded into the background, and the twinkling lights of Sedgely lay ahead.

"We shall be back home in a couple of hours," Hammond said. "But I think it would be prudent to take the lower road on our return. Don't you worry about those people. They're never likely to trouble you again. And your welfare will be my concern in the future. You're the bravest girl I ever met."

It was past one o'clock in the morning before the car pulled up in front of Hammond's house. The light was still burning in the lower rooms, and Sheila Hammond, with a white, anxious face, came to the door.

"I've been most terribly alarmed about you, Chris," she said. "I could not get it out of my head that something had happened to you. But who is this?"

"Well, something very nearly did happen to me," Hammond said. "If it hadn't been for this child here, I very much doubt if I should have got home again; and, even if I had, it would have been our home for very little longer."

"Why, it's Karma," Sheila Hammond cried, "little Karma, who was in hospital here so long with a broken leg!"

"She was very good to me," Karma explained. "I got hurt in the winter, and my people didn't know what to do with me, so they sent me to the hospital here. And Sheila used to come and see me every day. She was so good to me."

"It was when you were in Austria all that time, Chris," Sheila smiled. "I forgot to tell you anything about it. When Karma got better, I wanted her to stay with me altogether."

Karma shook her head almost sorrowfully.

"I couldn't do it," she said--"at least, not for long, I loved Sheila because she's one of us. Directly she came to see me in the hospital, I knew she was one of us. We wander about all over the world, and we speak all sorts of languages, but when we meet, even when we cannot understand one another, we know the Zingari. And Sheila told me that there was a time, years ago, when she wandered about the woods bare-footed as I am now. And she told me how you met her and made her love you, and how, because she loved you, too, she went to school and tried to forget all about the woods and the fields. Oh, I understand!"

"This is all very amazing," Hammond said. "Sheila, do you ever feel inclined to go back to it again?"

Sheila looked up with tears in her eyes.

"Oh, often and often!" she said. "I wake up in the night, and the longing comes upon me. Did I ever tell you that I can see in the night like a cat? Well, I can. And I don't mind telling you that it was very bad at first. Sometimes it was dreadful--before the boy came. And now it's quite different."

"Well, this has been a day to remember," Hammond said. "Now take that child in the dining-room and give her something to eat while I put the car away, and than I'll come hack and tell you all about it. You are going to have your way as far as Karma is concerned, for it will he no fault of mine if she ever leaves us again. You little know what she has done for us to-night."

Sheila sat listening to the story presently. It was all very strange and very wonderful. Karma sat there, not in the least elated, not in the least like one who has done something out of the common, and not in the least impressed by the comfort and luxury of her surroundings.

"Mean you want me to stay with you?" she asked. "Always?"

"As long as you like," Sheila smiled. "I want you to remain and he our adopted daughter. You shall have pretty dresses to wear and good food to eat, and you shall no to school and become a fine lady like I did."

Karma shook her head doubtfully. There was something appealing in the neat, sweet-scented bedroom in which she presently found herself, but, all the same, there was an eager alertness in her eyes and a suggestion of being on the defensive, as one sees in the actions of a dog in a strange house for the first time.

"I should love to he with you, for some things," she whispered, "because you are very good to me, And I'll try hard, Sheila. And if I happen to break away--"

Sheila bent over and kissed the quivering lips.

"My dear child, I quite understand," she said. "I have been through it scores of times myself. Now, good night, and don't forget that I am your friend, now and always."

It was the fifth day before the child was missing. She had left, apparently, early in the morning, with the break of day. She had taken nothing with her besides the scarlet blouse and skirt in which she had arrived. Even the boots and stockings were laid neatly on her bed, and with them a little ill-spelt note, asking forgiveness and telling them, in simple language, that the fields and the birds were calling, and that there was something that made her obey. It was a genuine grief enough to Sheila, but it had been nothing more than she had expected.

"I knew it was no use," she told Hammond. "It is rarely that one of us breaks away from the wild like I did, and I'm not really cured, even now."

"It is disappointing, though," Hammond said. "I only hope the poor child hasn't fallen in the hands of those people again. If she does, they will kill her, to a certainty. I'm going out in the car to see what I can do."

But a month elapsed before they heard of Karma again, and then indirectly through paragraph in a newspaper. A child had been found seriously injured by the roadside, and had been conveyed to the hospital at Slagborough. She had refused to give any account of herself or to say to what her accident was due. Hammond passed the paper across to his wife at breakfast-time, and went off without another word to get the car. They found Karma very still and very white, lying in a hospital bed. Her head was bandaged, and all the wealth of luxuriant black hair had been cut away. Sheila glanced at the nurse, who shook her head.

It needed no knowledge of surgery to see that Karma's end was near at hand. The wound and the shock to the system, to say nothing of the exposure, had done its work. Sheila leaned over the bed and kissed the child tenderly."

Tell me how it happened," she asked. Karma smiled up in return, but there was a certain suggestion of defiance in her black eyes.

"It was an accident," she said. "I love you, and I would die for you; but if it's the last word I ever say, it was an accident. Don't you get it into your head that anybody hurt me on purpose, because I know more about it than anybody else, and I say it was an accident. And when I'm dead, and people speak to you about it, you are not to forget what I'm telling you now."

"It's all very distressing and very sad," Hammond said, as he and his wife left the hospital an hour later. "I should like to believe the child, but I can't. Some blind, irresistible impulse must have taken her back to her own people, and one of those blackguards must have attacked her. They probably left her at the roadside, thinking that she was dead. It makes one's blood boil to think about it. And what can one do?"

"Nothing," Sheila said, tearfully. "You'll never get her to say anything else. She's loyal to the blood to the core. She will die as she has lived, and the secret will die with her."

And Sheila's words proved true.

SALTBURN scooped the beaded sweat from his forehead and flicked it from his fingers as it had been something noisome.

"I'd give," he muttered—"Heavens, what would I not give for a tub of sweet, wholesome, hot water and a piece of yellow soap? Ralph, I stink—we both of us stink! The effluvia has got into the pores of my skin. I am loathsome and repulsive to myself, and my mind's getting as vile as my body!"

Ralph Scarsdale sat up like a startled rabbit in a field of corn.

"Now, that's dashed odd!" he gurgled. "I've been sitting here for the last hour, sweltering in my own juice, and thinking exactly the same thing. It's queer, Ted, my boy, very queer. I suppose this infernal country is getting on our nerves. Were we not the best of friends?"

"Pals for years," Saltburn said, as if making a confession he was ashamed of—"school and college. Made fools of ourselves together, lost our money together, and came out here together. Three years ago? Three centuries!"

"Ever feel at times as if you hated me?"

"Yes, you and myself and all creatures, black and white. It's the fever of the place, my son. It's in the air that rises from this dismal swamp. You can produce the same effect by drink, if you take enough of it. You hardly call a man a murderer who kills his best friend during an attack of delirium tremens. Yet, if I put your light out here, and a slaver-hunting gunboat happened along at the time, I should swing for it. And yet it's just the same thing. Hartley warned me of it before we came out. He said it was a disease you catch, the same as Yellow Jack. Boil it down to the formula of the medical dictionary, and it's homicidal mania."

Now, this was a strange conversation for two bosom friends to be having in the dead of night on the beach at the mouth of the Paragatta River. It was the first time for months that either of them had given to the other an insight into his mind. For months they had been growing more moody and silent. They had little tiffs—whole days when neither spoke. And Saltburn was drinking too much whisky, Scarsdale thought. And Saltburn knew that Scarsdale was overdoing it, otherwise why was it necessary to open one of the case bottles so frequently?

They had drifted here, broke to the world, glad to look after copra for old Hans Breitelmann, the fat and prosperous old Dutchman down at Dagos. And they had stayed because they had heard the story of the Redpath Pearls. The Redpath Pearls were there hidden in the swamp, all right. It was no fairy tale; Joshua, the Papuan servant, had seen them once. It was Josh who kept them going, who stimulated curiosity and, be it said, greed. For the sake of their bodies, to say nothing of their souls, they should have turned their backs upon this hideous swamp, and they knew it. But, if they could find the pearls, they were made men. The pearls were in little wicker baskets attached to a float in the middle of the swamp. These Redpath had hidden there before the Papuans murdered him, and they were there till this day. But it was impossible to fish or boat or work an oar in that oily blue-and-gold scum, which the tide hardly touched. Josh had a legend to the effect that, at certain spring-tides, the swamp was passably dry, and, given a north-east gale of sorts, the tide was held back, sometimes for a day or two, and then under the sun the mud caked hard, and one could cross the lagoon dry-shod. He had seen this more than once himself, but not since Redpath had hidden the pearls there. If the excellent gentlemen would only wait—

And they had waited, but they were looking into the bloodshot eyes of stark tragedy. The heat, the loneliness, the desolation of it, had long since frayed their nerves. They had come to the point now when they no longer talked, but merely muttered. It was weeks since eye had looked into eye, and times when a smile might have suggested insanity. There was a mark on the side of Scarsdale's neck—a red mark—and Saltburn wondered how it would look with a razor-slash across it. And Scarsdale's sister's letter was in his pocket, and her photo in a case next his heart.

Josh, the Papuan, was squatting somewhere near in the reeking darkness, watching. Nothing disturbed his serenity; he was troubled by no scruples or frayed nerves. He was just eleven stone ten of original sin—as all Papuans are—without heart or conscience or bowels of compassion. He was a loathsome thing, born of the meanness and rottenness of corruption, a human upas tree, a hawk to be shot at sight. He would have murdered his employers long ago had it been worth his while to do so. He had argued the matter out philosophically a good many times. But they had no money or articles of value, and their premature demise would have meant the cutting off of Josh's whisky. He was prepared to crucify creation for a bottle of "square-face," Still, this taking off of the white men would only have meant one colossal spree, followed by a total abstinence, perhaps, for years. It was far better to get just comfortably drunk every night, and this inevitably was the reason why Scarsdale and Saltburn suspected each other of overdoing it.

And now there had come along a temptation that shook the philosophy of the Papuan to its foundations. Eight, nine, ten cases of whisky had arrived by the last copra boat from Dagos, awaiting Breitelmann's orders. And Josh's strong point was not arithmetic. He figured out that here was enough whisky to carry on a fine, interminable, whole-souled jamboree to the confines of time. He pictured himself alone with these cases. They would have to be smuggled away and safely hidden, of course. One by one the bottles would have to be stolen, and their places taken by empty bottles filled with water. If he was caught at the game, he would be shot on sight, but the prize was worth all the risks. Therefore it resolved itself purely into a matter of time.

If the Englishmen stayed, it was all right. If they resolved to chuck the whole thing, then it would be wrong. If they went, they would send up to Paterson's station for help to clear the stores, and then the glorious opportunity would be lost for ever. And they were talking about going at that very minute. Scarsdale and Saltburn had seen the red light—they had not been in this accursed country three years for nothing. They had seen a new-comer shot and nearly killed merely for telling a funny story and laughing at it afterwards. Some spring had been touched, and the two friends were nearer together than they had been for months. And Josh's sharp ears took in every word of it.

He came towards the crazy hut and kicked the fire together with a heel as hard as ebony. The fire was a mascot, and kept some of the mosquitoes off. In an attitude of fine humility Josh waited for orders.

"Ain't any," Scarsdale said curtly. "Be off, ye scoundrel!"

"Big spring-tide, morning," Josh grinned amusedly. "Un biggest spring-tide since three more years. Wind am gone north-east."

Surely enough, the hot north-east wind was reeking with rottenness and corruption, and blasting like a furnace at the door of the hut. The man who takes the future in his hands, and is prepared to back it against the forces of a continent, is ever a gambler, and Scarsdale's nostrils twitched. A red spark gleamed in Saltburn's eyes. If what Josh told them was true—

Half an hour ago they had practically made up their minds to leave the place. The resolution was wiped off their mental tablets as by a sponge. Simultaneously the same thought leapt to each mind. They had been here three years, hungering, thirsting for these pearls. They had been pushed to the verge of insanity for the sake of them. And if success came now, it meant everything. It meant fortune, and comfort, and clothes, and hot baths, golf, shooting, hunting, fishing, and, for one of them—Saltburn—the kisses of Mary Scarsdale on his lips. And, curiously enough, he could not at the moment think of her as Scarsdale's sister. There was no cohesion in the world just then; everything was resolving itself into original atoms.

Who was that chap sitting on the other side of the fire? For the life of him, Saltburn could not put a name to the other. It was merely a man—a superfluous, unnecessary man, who was probably after the pearls also. In other words, an enemy to be watched. If the pearls were to be found, Saltburn was going to have them. Why should he trouble about the other fellow? Oh, the poison was rank and strident in the air to-night!

And Scarsdale was following Josh with a hard, vulpine curiosity.

"Very big ebb," the rascal went on cheerfully, "an' much sun to-morrow. Lagoon be dry by nightfall. Perhaps dry for three—four days, if wind can hold on. An' pearls—dem hidden in lagoon."

Josh passed on to his own quarters, his teeth showing in an evil grin. He knew exactly what the two men were suffering from—he had seen the disease often before. He had seen battle and murder and sudden death spring from it. Generally it took the more prosaic form of drink, followed by the purple patches of delirium tremens; but Scarsdale and Saltburn had successfully avoided that, though they suspected one another—to Josh's material advantage. He had been racking his brains for a way of keeping the two on the soil a little longer, and, just as mental resource had failed him, the wind had changed. He had always prophesied that, sooner or later, the wind and tide would conspire, and the sea would give up its dead, so to speak. But he had never really counted on it. He would not have dared to touch the pearls himself, for they were haunted. With his dying breath Redpath had laid a spell on them. The hand of the Papuan that touched the shining discs would wither at the wrist and rot, because Redpath had said so, and he was a man of his word. Josh did not care a red cent for the pearls, but he was very keen and very desperately in earnest so far as concerned the cases of whisky. Therefore the change in the wind had come just in the nick of time. He would have three or four days more, at any rate, for he had seen at a glance that the men did not mean to go before they had had a shot at the pearls. In the ordinary course of things, they would have discussed Josh's news. A few months ago they would have caught at it eagerly.

As a matter of fact, they turned into their respective bunks with never a word passing between them. The hut simmered in the heat. There was a deadly silence save for the sharp ping of the mosquitoes. It might have been taken for granted that the two men were fast asleep. As a matter of fact, each lay in his bunk looking into the darkness with hard, restless eyes.

"I shall never sleep again," Scarsdale was telling himself. "And yet there was a time when— How many centuries ago was that? No such thing as sleep in this accursed continent. If I could get away from it! Only let me finger the pearls! They are as much my property as anybody else's, and I do not see why I should share them with anybody. Heavens, if I could only sleep!"

He dropped into a kind of soddened doze presently, yet half conscious of himself all the time. He tossed and muttered uneasily.

"I'll get 'em," Saltburn was telling the darkness. "See if I don't! Why should I share them with anybody? I spoke to Josh first. Funny thing! I'd a queer notion in my head that I'd got a partner in the business. But the other man who was here to-night is no partner of mine. Bound to be civil to the chap. But when he comes talking of shares And Scarsdale's drinking too much whisky! Why should I worry about that? And who is Scarsdale? And where have I heard the name before? Sleep, you fool, sleep!"

He grabbed at himself with a certain despairing rage. But he, too, dropped off presently into the same strange, half-alert semi-unconsciousness till the dawn came and the sickly, languid day rose from the sea of oil and ooze. Scarsdale had disappeared, but Saltburn thought nothing of that; he had actually forgotten the very existence of his friend. There was a little more sign of dampness in the wind to-day; then came the blessed consciousness of something to be done. If the wind held good, he would have the pearls or perish in the attempt. And the wind did hold good. The orange-yellow mist faded away, and the sun beat fiercely over the mud of the lagoon, while the reek of a thousand acrid poisons filled the air. The sluggard tide was creeping in from the sea again, but it did not reach the lagoon, for the fierce level beat of the north-east wind kept it back. Saltburn grinned as he saw the hard, dry mud caking on the surface. He asked himself no questions as to Scarsdale. It never seemed to occur to him to wonder where the lake had gone to. When the fiery orange sun began to dip, he would go out to search. And when these pearls were his, ah, then—

The great copper sun was beginning to slide over the shoulder of the mango groves before Saltburn set out on his journey. He had the air and manner of a man who walks in his sleep. His red-rimmed eyes were hard and vacant; his lips twitched oddly, as if they had been made of elastic. It was all one to Saltburn, as he had not tasted food since he had dragged himself from his bunk. He had touched the ground in accordance with the laws of gravity, but to him it was as if he were plunging along knee-deep in cotton-wool.

He came to the edge of the lagoon presently—came to the edge of the liquid ooze of amber and gold and crimson, where the tide had ebbed; but the brilliant dyes were there no longer, and the flow of the lagoon was baked to grey concrete. He crept across it like an old man. Now and then a foot would go through the crust and bring him up all standing. He knew his way by heart. Away to the left was the remains of a wreck, cast up there ages ago by some great storm or intense volcanic disturbance, and there Redpath, flying headlong from his foes, had cast the pearls before he had been sucked down by the mud and suffocated by the slime and ooze and filthy corruption of it. How Redpath had contrived to get so far was a mystery.

He had found some sort of a footing, some sort of a trail on the lagoon by accident. Another fifty yards, and he might have reached safety and the river. For the river was there, as more than one rascally slaver knew. They found salvation there sometimes, when His Majesty's gunboat Snapper was more than usually active. Saltburn was on the spot at last. Down here, under the sand somewhere, the wicker baskets containing the pearls lay. And Saltburn was groping for them like a man in a dream. He broke his way through the crust on the mud and plunged in his arms. He was black to the shoulders, as if he had been working in ink. He fought on with a sudden strength and fury; new life seemed to be tingling in his veins. Presently his right hand touched something, and he drew it to the light. It was one of the small wicker baskets, dripping and slimy. Inside was a handful of round, discoloured seeds— the pearls beyond a doubt.

Saltburn burst out into a drunken, staggering, hysterical yell. Fortune and happiness, comfort, prosperity, all lay in the hollow of his trembling hands. He grasped blindly and hurriedly, and again and again with the same pure luck. One, two, three, four of the little baskets! Hadn't somebody told him that there had only been four of the baskets altogether?

Now, who the deuce had he got the information from? Why, Josh, of course! And where was Josh? Confound him!

Josh was not far off. He was standing on the edge of the lagoon, showing his great white teeth in an expansive smile. He was waiting for Scarsdale to put in an appearance. Josh was a bit of an artist in his way, with a fine eye to an effective curtain. And the air was heavy with impending tragedy. There would be murder done here, or Josh was greatly mistaken. And when these two bosom friends had choked the life out of each other. Josh would collect the whisky and report the matter, and that would be bhe end of it.

Scarsdale was coming now, approaching Saltburn from below the wreck. He stood for a moment contemplating Saltburn in a dull, uncomprehending way. He, too, was like a man who walks in his sleep; he had the same hard, red-rimmed eyes, the same elastic twitching of the lips. Who was this mud-lark, and what was he doing with another man's pearls? It was that blackguard Saltburn, of course. Curse Saltburn! The fellow had followed him everywhere—had been the bane of his existence. He had always hated Saltburn from the bottom of his heart—could never get rid of him. And here was the scoundrel robbing him of his fortune before his very eyes!

With a roar of rage, he dashed forward.

"Get out of it!" he croaked. "Go back to your kennel, you hound! What do you mean by coming here and robbing me of my hard-earned money? You were a sneak and a thief even in your school-days!"

Saltburn showed his teeth in an evil grin. "Come near me, and I'll kill you!" he said hoarsely. "Come near me, and I'll take you by the throat and choke the life out of you! Call me a thief, eh? What do you call yourself, then? You'd take the coppers from a blind man's tin! Keep away, or I shall do you a mischief!"

Scarsdale came on, gibbering and muttering. They were at grips, to the great delight of Josh, standing like a black sentinel on the edge of the lagoon. Ah, this he had engineered carefully and cleverly! Why should he take the trouble to kill those two white men when they were so ready to destroy each other? They had never done him any harm, either; on the contrary, he had enjoyed a great many splitting headaches at their expense.

He saw the white men grip and reel and stumble; he could hear their cries and curses, as the bark of civilisation peeled off and the raw primeval man underneath stood out in his hideousness. Josh was no longer watching two men, but two wolves fighting for each other's throats. He saw how the mud was being churned up in the struggle, he saw flakes of the crust break away like ice on a lake in the springtime. It was all very well for one man to walk circumspectly on the thin rind of dry mud, it was possible to make holes in it and be safe, but here was a different matter. The ice had given way, so to speak, and these men were in a sea of mud, with the certainty of a horrible suffocation before them. They were sinking deeper and deeper in the pernicious slime without being in the least aware of it. All this Josh saw, and a great deal more from his seat in the stalls.

But there was one thing he did not see, for it was concealed under the edge of the bank that formed the margin of the sluggish river. He did not see a boat belonging to H.M.S. Snapper, full of blue-jackets and armed marines, creeping cautiously along in search of the slave dhow that lay concealed, as the commander of the Snapper very well knew, in a creek hard by. The look-out in the stern had a keen eye and ear for sign and sound, and at the hideous din going on just over his head he stopped. It was no difficult matter to climb up the sun-dried bank and investigate. And Lieutenant Seaton understood. He had heard of this form of malarial madness before. He swept his eye round the lagoon and took in the nigger in the stalls like a flash. And Josh realised the delicacy of the situation all too late. A couple of bullets whizzed by his ear, and he stopped. A sergeant of marines beckoned to him and he went.

"Rise up, William Riley, and come along with me," the sergeant quoted. "Now, sir, what are we going to do about this?"

"Get back to the ship," Seaton directed, "and hand these two poor devils over to the doctor. Take the nigger with us as well. One of these madmen thinks that those baskets are full of pearls. Better humour them and take the baskets along. The black rascals of the creek will keep for an hour."

Scarsdale and Saltburn lay in the bottom of the boat, half suffocated, wholly exhausted, and quite oblivious to their surroundings. They were both in the heart of some hideous nightmare. Whether they came out of it or not was very largely a matter of indifference. The commander of the Snapper looked at his deck, then looked at the doctor, who seemed to have grasped the situation.

"Mad as hatters," the doctor muttered. "These chaps have got malarial mania, which precedes chronic insomnia and madness. Good food and sea air is the cure. Well get these chaps bathed, and I'll put a few grains of morphia into each, and they'll sleep the clock round. When they come to themselves, they ought to be as right as rain."

"Um! Morton says that it was no delusion as to the pearls. He says they are real pearls and worth a huge fortune. I'll bet that nigger can tell a story. Seaton, send the Papuan to my cabin."

Josh made the best of it. He told the story of the Redpath pearls and how they had been found. He had a good deal to say also on the score of the slave dhows and their artful ways, all of which pleased the commander of the Snapper very much. But he quite forgot to say anything about the whisky, and that must remain a secret.

"I've got those chaps cleaned and in bed," the doctor explained, as the armed boat dropped away again, with Josh in the bows to act as guide. "When I soaked them out of the mud, I found an old chum of mine called Scarsdale. Oh, yes, I pumped some considerable morphia into them, and they dropped off peacefully as kids. Shouldn't be at all surprised if they slept for the next four-and-twenty hours. Anyway, we found 'em in the nick of time."

It was, as a matter of fact, the morning of the second day before Scarsdale stirred and opened his eyes. A brace of slave dhows had been destroyed and their crews shot, and the Snapper was in blue water again. The fine crisp breeze blowing in through the port-hole swept Scarsdale 's cheek, and a pure hunger gripped him.

"Where the deuce am I?" he muttered, "And what a head I've got on me! If this is a dream, Heaven send I may go on with it!"

"Then we're dreaming together," Saltburn said from the next bunk. "We're on a gunboat, my son. Here, let's try to think it out. Where were we? And what the dickens were you and I quarrelling about?"

"The pearls!" Scarsdale cried. "We were both after the pearls. The wind had gone round to the nor'-east. Don't you remember? We must have been fighting like cats until these good chaps picked us up. I'd bet a dollar they were creeping along after slavers and spotted us. And we were trying to murder one another, old boy! By Jove, it is coming back to me a bit at a time!"

They lay there thinking it out in silence, a strained, shamed silence, for each was holding himself as actually to blame. They were still deep in retrospect when the doctor looked into the cabin.

"Well, you chaps?" he said breezily. "Hallo, friend Scarsdale! Haven't forgotten Monroe, eh? Because that's me. And this is the Snapper, and I'm her doctor. Small place the world, after all, isn't it? Oh, yes, we took you off the mud all right. We got it all out of a picturesque rascal who said his name was Josh. Friend Josh gave us the slip during a little scrap we had up the river yesterday, so he's done with. Now, don't you fellows say anything and get blaming yourselves. I have heard of your particular trouble many a time before. And, however, luck came to you just at the right time. We saved your lives and your pearls, too. One of our men, a judge of stones, says they are worth a couple of hundred thousand quid easy. A few good meals and a day in bed and the air will put you as right as right can be. We fetched your kits away, and your clothes are here. Now get up and come to breakfast."

"What's the next move?" Scarsdale asked unsteadily.

"Back home," Saltburn said, with lips that trembled. "England, home, and beauty. And jolly well stay there, as far as I'm concerned. Old boy, as far as that goes, I don't care if the last two years be never mentioned again."

"It's a bet," Scarsdale said fervently.

MACHIN puts the blame on to the the editor of the Arena, and the latter complains that he was grossly deceived. Now, the Arena is an exceedingly important journal, and, as everybody knows, carries great weight with people of intelligence. It is a sixpenny weekly, and devotes a good deal of its space to the better fiction. So therefore it cannot be assumed for a moment that Cruchley, the editor, allowed himself to be made a party to a deliberate fraud on the British public.

The fiction particularly favoured by the Arena belongs largely to the cameo type—exquisitely polished sketches and clear-cut emotions and the like. There must be at least half a dozen novelists of the front rank who have to thank Cruchley for their present position. Therefore Cruchley, when he received that eloquent trifle entitled 'The Liver Wing,' written over the signature of Laura Jane Parlby, lost no time in asking the author of the story to call upon him. It was just the kind of stuff he wanted, and he was naturally desirous of making the best bargain he could before his fellow editors came in. The sketch in question, had it been Scotch, would have belonged to the Kailyard school, but being frankly English, and Arcadian at that, was still waiting for the appropriate epithet. Once that was done, Laura Jane Parlby was a made woman, and the circulation of the Arena would indubitably be enhanced. Now, some people would have sneered at the carefully careless simplicity of 'The Liver Wing'; some people would have failed to see its delicate humour. It was a mere account of an unselfish old maid who never in her life had partaken of the delicacy in question. In her youth she had never desired to rob her parents of the dainty; when she became independent and set up house for herself, it was her invariable practice to prevent the precious trifle to other people.

All this sounds very frivolous, of course, but, as any editor worthy of his salt knows, it is merely a matter of treatment. And every editor worth his salt, too, is naturally on the lookout for a boom. Cruchley was exceedingly particular whom he did boom, but it seemed to him now that here was a legitimate object and scope for opportunity. Therefore it was that he wrote to Laura Jane Parlby, and asked her to call upon him. Could she make it convenient to look in after twelve o'clock some Thursday? There came a wire in response to the effect that the very first Thursday that ever was should see the meeting between writer and editor.

It was a considerable disappointment, therefore, for Cruchley when there presented himself a big man with a big beard and moustache and tanned face, to say nothing of a shabby Norfolk suit, who announced himself without any sense of fitting humility as the author of 'The Liver Wing.'

"The deuce you are!" Cruchley gasped in dismay.

"Nothing wrong about it, is there?" Machin demanded.

"Well—er, not precisely. But, naturally I expected to see a lady. You know, I made rather a prominent feature of 'The Liver Wing', in last week's Arena. I wrote a leaderette on the subject. I told my readers that we had discovered a new humorist—the rare type of humorist with the art of blending tears and laughter. I went so far as to insinuate that here was another Jane Austen with a flavour of George Eliot."

The big man smiled.

"I think I understand you," he said. "You see, at one time I took a hand in the game—I mean that in my family there were several journalists, and I have learnt something of the inner workings of a newspaper. Now precisely what did you expect Laura Jane Parlby to be like?"

"Well, you see, one goes, to a certain extent by the name. Laura Jane Parlby sounds so delightfully Victorian. One pictures her in a white, creeper-covered house, furnished with Georgian simplicity; one sees her going about the village with her charity basket on her arm, carrying sunshine into the Tudor cottages; one marks her as a friend of everybody and the depository of all kinds of sentimental little secrets. She should be tall and thin, with blue eyes and grey hair, and, of course, her lover should have perished at sea or something of that sort. She should be an excellent cook, and people should throw their champagne on one side when she makes them a present of her rare old rhubarb wine. Oh, dash it all, my dear chap, you know exactly what I mean. I expected to see her come in here wearing one of those black silk dresses that stand by themselves, to say nothing of a big white bonnet or balcony hat. And when you came in here just now, looking—if you will pardon a simile—more like a gamekeeper than anything else, I was disappointed."

Machin made no reply. He did not appear to be in the least annoyed in being taken for a gamekeeper—indeed, it was doubtful if he heard what Cruchley was saying, for he seemed deeply mersed in thought. He came to himself with a start.

"I beg your pardon," he said. "You see, I am a bit of a sportsman, and I should be a gamekeeper if I could afford to preserve. But I don't see that the fact of my being a man makes any difference. I can go on writing under the name of Laura Jane Parlby and the public will be none the wiser."

"That's not good enough for the Arena," Cruchley said promptly. "We have far too sweet and clean a reputation for anything of that sort. The truth must be told, though it will be a great disappointment and we shan't do anything like so well out of your work. Mind you, it's rattling good stuff, and I congratulate you warmly."

Machin contemplated his boots gloomily.

"Without knowing it, you are putting me in a very tight place," he said; "and if your paper is so particular, then I must violate a confidence and tell you the whole facts. Now, Mr. Cruchley, do I look like the sort of man who could write a story like 'The Liver Wing'? Do I look like a man with a soul?"

"Not a bit," Cruchley said promptly. "Why?"

"Well, you see, I have an Aunt Jane. Whether she is Laura Jane Parlby or not does not matter. We will assume for the sake of argument, if you like, that after a great many years she suddenly discovers that she can write. Perhaps that is not quite the right way to put it. Somebody discovers in an old desk of hers a little sheaf of stories, and reads them. Say it's me, if you like. And I urge her to publish them. She looks at me as if I had suggested that she should commit some crime. She's a gentle, kindly soul, who never likes to say no to anybody. At length she permits me to send one of those sketches to a paper which shall be nameless, and she nearly dies of heart disease when she finds the story has been accepted. And you can imagine the consternation of the poor old soul when she got your telegram. Something had to be done, or assuredly I should have lost my Aunt Jane. She was delighted, of course, to feel that her work was worthy of publication but the suggestion of publicity filled her with horror. She began to anticipate hordes of journalists bearing down upon her ivy-covered cottage to interview her. It was I who suggested the plot. I write a bit, anyhow; she was to do the stories, and I was to pretend that I was Laura Jane Parlby so far as putting the public off the scent were concerned. Mind you, I didn't mean to tell you this. I shouldn't have done so only you've been so straightforward and so loyal to your paper. I hope all this is satisfactory."

"Oh, eminently!" Cruchley cried. "You see, it makes all the difference in the world. You can pretend what you like—it doesn't make the slightest difference to us. You can practise a mild deception on the British public, but it leaves our editorial acumen untarnished. We knew that 'The Liver Wing' was the work of a woman, and so long as we are assured of the fact that there is a genuine Laura Jane Parlby, we can go on with the boom. I'd like to run down a little later on and see the talented authoress. When she gets more accustomed to the fame which is surely coming she won't be quite so retiring."

"Oh, you mustn't do that," Machin protested. "You haven't the remotest notion what a sensitive woman she is. And how can I go back home and tell her that I have betrayed her secret in this shameful way? My dear fellow, you must regard this conversation as absolutely confidential. I have made it all plain sailing for you, and I will see that you get plenty of stories. I suppose there are about a score of them altogether, and I hope a little later on to induce my aunt to write a book."

Cruchley's eyes gleamed. For the proprietors of the Arena were also publishers. In his mind's eye he could see an exceedingly good thing in this. And, besides that, he personally was going to add to his reputation by introducing a new novelist to the world of letters.

"Very well," he said. "I am exceedingly obliged to you for coming here to-day and taking me into your confidence in this candid manner. And mind, it is quite understood that I am to have the refusal of all Laura Jane Parlby's work. We can afford to pay her far more handsomely than the majority of magazines, and I need not remind you what a start in the Arena means. Before many months are over, Laura Jane Parlby will be famous."

Strange as it may seem, this information did not appear to afford any particular satisfaction to Machin. Possibly he was fond of his aunt, possibly he feared what the effect would be of verbal intrusion into her Arcadian paradise. He went away somewhat thoughtfully, and for the next few days Cruchley heard nothing of him. Then the batch of short stories arrived with an intimation that a book was in contemplation; and, in the fullness of his heart, Cruchley dispatched a cheque which a little later caused some unpleasantness between his commercial-minded employers and himself. He defended himself on the grounds of expediency; he was quite sure that the money would come back a hundredfold. That the house had secured a new literary star of magnitude he did not for a moment doubt. And certainly his prophecy was speedily fulfilled. From the very first the discriminating public drank eagerly at the pierian spring as filtered to them through the brain of Laura Jane Parlby. Three months, and everybody was talking about Laura Jane Parlby—there had been no such phenomenal boom since the days when the Scots came down from the north and captured a shrewd and discriminating public.

Never had a fame been more cleverly or easily exploited. And the talented authoress herself appeared unconsciously to be playing exactly the role that Cruchley would have chosen for her. She seemed to be absolutely unaware of the fact that she was famous. It was understood that she read no papers, and no one could say anything about her ways or habits—indeed, Machin saw to that. He had a fine eye for a wandering journalist in search of copy, as more than one of his tribe can tell to his cost. And meanwhile, Miss Laura Jane Parlby went quietly about her daily life, tending her house and her old-world garden and visiting her pensioners. Not the most audacious or daring brother of the pencil had ever had speech with her; not one of them had got beyond the front gate. At the first sign of danger Machin loomed big and strong on the horizon, and Miss Parlby fled into the house. The whole thing was beginning to get on Machin's nerves.

"I'm getting rather fed up with this," he confessed, as he discussed the matter with his particular chum, Martin, the village doctor. "I can hardly get away for half an hour now. The dear old lady hasn't the remotest idea what people are saying about her. She thinks she has written two or three stories which are just good enough for print, and that's all there is to it. That she's a great personage, she's not the remotest idea. If she knew the truth she'd have a fit. Upon my word, I shall have to take a holiday. My idea is to change our names and go abroad somewhere. I could get a companion for the old lady and settle her down in some old-fashioned French town, then I might pop back and get a bit of shooting. I'm quite soft for want of exercise."

"But she's bound to find out sooner or later," Martin urged. "The papers are full of her. Most of the details are all lies, but that doesn't make any difference. The village has been talked about and photographed and all the rest of it, and I'm told that one of the livery stable keepers at Frampton is organising weekly chara-banc excursions to run over here with a view to excursionists seeing Laura Jane Parlby's cottage. My dear chap, you'll have them all over the garden after a bit picking flowers and carving their names on the trees. Why don't you break the thing gently to Miss Parlby? If you don't do it somebody else will. You can't expect everybody to keep a bridle on their tongue every time they meet your aunt."

Machin did not appear to relish the prospect. He had his own reasons for pursuing a policy of silence.

"I shall have to do something," he said. "Of course, it's all very well in one way. So far as the money is concerned, it's simply rolling in. I suppose in England and America they must have sold at least two hundred thousand copies of the last book. I don't know what to do with it."

"You don't know what to do with it? How do you mean?"

"Well, that's what it comes to," Machin said with a slight flush on his face. "You see, the dear old lady doesn't care anything about the money. She persists in thinking that she makes about a pound a week, and so long as she has an extra sovereign a week to spend on her pensioners, she's perfectly satisfied. And all the rest comes to me. You needn't look at me like that, because I'm absolutely entitled to it. And yet I can't spend a penny of it. I'm like a poor chap who finds himself shipwrecked on an island of gold."

It was exceeding hard luck, and Martin was correspondingly sympathetic. It was all very well to talk about getting Laura Jane Parlby away, but she could be obstinate enough in some respects, and she absolutely declined to leave her beloved village. Martin's suggestion that he should call upon her and discover some alarming symptoms which called for a change of air ended in absolute disaster. The old lady looked up from her knitting with an air of mild surprise.

"I don't think there's anything the matter with me," she said mildly. "It is my dear nephew, Charles, who wants a change. Indeed, I'm getting quite anxious about him. I cannot understand why he always looks so troubled and worried."

"Oh, possibly some family weakness," the doctor said. "I shouldn't wonder if you shared it yourself. Two or three months' travel on the Continent would make all the difference."

Miss Parlby clicked her knitting needles together. She looked wonderfully soft and amiable, she made quite a picture.

"I shall never leave here," she said. "Nothing would induce me to. Ever since my dear father died I have not been a mile beyond the village. I went to London once, but I was quite glad to come back the next day. I could not bear the thought of dying anywhere except amongst my own people."

"It's no good," Martin confided to Machin afterwards. "I can't get the old lady to stir. Your only chance is to go somewhere at a distance and break a leg or an arm or something of that sort. Then the old lady will hurry to your side quite in the traditional Victorian manner."

But there was no occasion for Machin to go to a distance in order to fracture a limb, because Fate took a hand in the game and did that for him. The God in the Car took the shape of a young horse in conjunction with some posts and rails, and when Machin scrambled to his feet, he needed no master of surgery to tell him that he had broken his arm. It was a pretty bad fracture, to say nothing of an injured rib, and it looked as if Machin would have to lie up for a month at least. Miss Parlby was more than sympathetic. She knew the value of quiet to an invalid, and she took the liberty of even suppressing Machin's letters. She saw with perturbation that some of these letters were arriving regularly from the office of the Arena, but thought they might be of the last importance—Machin was not to see them. At the end of the second week there came a visitor with a very pressing demand that Miss Parlby would grant him the favour of an audience. She was only human, after all, and she thrilled when she saw from the visitor's card that he was the editor of the Arena. She had all the ordinary person's veneration for the editorial fraternity, and with some considerable agitation donned her best cap in honour of the occasion.

"I am exceedingly sorry for this intrusion," Cruchley said, "but I was so anxious that I had to come down and see you. I have heard nothing for the last three weeks. And I have not a single short story by me. I trust you've not been ill?"

"I am never ill," Miss Parlby said. "I suppose you are disturbed because you have heard nothing from my nephew, who transacts all my business for me. I regret to say that he is lying in bed with a broken arm."

Cruchley breathed a little more easily. He knew something of the moods and vagaries of the artistic mind, and he had been somewhat fearful that wounded vanity was at the bottom of that disturbing silence. You never could tell, and again there was the possibility that a rival editor had gone one better in the way of price. Even the artistic mind is not always above sordid considerations like these. So it was all right, though Cruchley was uneasily conscious that he had broken a promise in intruding upon Miss Parlby. Doubtless she had been so taken up with her nephew that she had forgotten everything else.

"I am very sorry to hear what you say," he murmured. "I shall be able to explain to our readers now that a domestic misfortune has dragged you from your desk."

"Oh, dear, no," Miss Parlby explained. "I hope I know my duty to my nephew. There is no question of dragging, I assure you. I have cheerfully put everything else on one side since he has been laid up. One could not think of letters when there is illness in the house."

"I wasn't thinking about letters," Cruchley stammered, "but more of those beautiful stories."

Miss Parlby looked slightly puzzled. No doubt this was an exceedingly clever and brilliant young man, but he seemed to be labouring under some sort of delusion.

"Are they really worth talking about?" she said. "Do you know they were never meant to be seen at all? They were more in the way of little innocent notes, just as if one played at writing to oneself. I used to do that as a child. You see, I was never lucky enough to have a playmate."

Here was the real human note, and Cruchley responded to it promptly.

"Charming, charming," he exclaimed. "A quaint and simple conceit indeed."

"Conceit!" Miss Parlby echoed. "I don't understand. I have never been called conceited before."

Cruchley stammered something in reply. What on earth was the matter with the woman? Was she trying to take a rise out of him? It was ridiculous to believe that one whose style was almost purely Addisonian should fail to understand the meaning of the application of his phrase.

"But it is so interesting," he said. "It will be quite a new note for our readers. They will be delighted to hear that you began your literary career by writing letters to yourself. That, no doubt, is where you learnt the rare art of prose introspection. If I may say so, that is one of the outstanding features of your wonderful workmanship. I suppose your short stories grew and grew until they attained that marvellous finish and style."

A little red spot burnt on Miss Parlby's cheeks.

"I quite fail to understand you," she said coldly. "It is not very good taste, sir, on your part to make fun of an old woman like myself. I never aspired to be an author, and I was exceedingly sorry when my nephew found those poor little efforts of mine. He persuaded me to let him have them, and when he told me they were going to be published in one of the magazines, nobody was more astonished than myself. Not that I have ever seen them. I should have been perhaps ashamed and uncomfortable if I had realised that the world had been taken into my confidence through the medium of a newspaper."

"Extraordinary," Cruchley murmured, "quite extraordinary. One of the vagaries of genius, in fact. And yet I assure you that I never printed a score or so of short stories with more pleasure in my life. And I am considered a judge."

"There is some dreadful mistake here," Miss Parlby said. "All I had to go on was a handful of notes, just silly little thoughts that occur to solitary people. You see, I read a good deal of poetry, and I have ideas for poems, though I don't in the least know how to write them."

"I am sure you could if you tried."

"I am sure I couldn't. At any rate, I handed those notes over to my nephew, and he said they had been published. They would not have made much of a story altogether."

"And what about the books?" Cruchley asked.

A cold fear was clutching him, a bead of perspiration stood on the editorial brow. Miss Parlby's gentle puzzled amazement fairly frightened him.

"I have not the remotest idea what you are talking about," she said. "My dear sir, do you actually think I am capable of writing a book? I am afraid that somebody has been grossly deceiving you. And you spoke just now as if I am a regular contributor to your paper. It looks to me as if someone has actually had the impertinence to make use of my name. Now I see why my friends have been amusing themselves at my expense. All sorts of funny little hints and suggestions. I thought at first that you were making fun of me. What vulgar minded people call chaff, I believe. You had better see my nephew."

"I am emphatically of the same opinions," Cruchley said grimly. "I will come down when he is better and interview him. If I have unconsciously said anything to offend you, I beg to apologise most humbly. Possibly the mistake has been mine."

Cruchley went back to London thoughtfully, and by the time he reached his office he began to see daylight. It was a fortnight later before he went down to the Sweet Auburn village again and confronted Machin.

"Now, you blackguard," he said, "tell me all about it. A nice mess you've got me into."

"Well, practically it's your own fault," Machin said. "I sent you a pretty little short story over the signature of Laura Jane Parlby. As a matter of fact, she was my inspiration and I thought it would be a neat idea to assume her name. Then you wrote and asked to see me or her, and I came. When I told you I was the author of the yarn, I could see that you were most bitterly disappointed. You told me pretty plainly that if you could father the stories on to some dainty mid-Victorian old maid, there was a big boom in front for the stuff. Now, I had written about twenty of those yarns, and I began to smell large money in them. I admit the inspiration came from my aunt, but the work was my own; and whether you like it or not, you are bound to admit that they were rattling good stories, and the public has endorsed your verdict. Well, I wasn't going to disappoint you, and I wasn't going to disappoint myself either. You asked for Laura Jane Parlby, and I was in a position to deliver the goods. So to speak, I had her in the ice chest. It seemed a pity to spoil a beautiful romance like that for the sake of a virgin aunt. I knew that she would never hear about it, and even if she did, she would forgive a little innocent deception like that. So I allowed you to think that I was merely a go-between to shield her lavender-scented genius from a vulgar and curious world. You seemed so dead keen upon the whole thing that I hadn't the heart to undeceive you. And, in any case, you had no business to have come down here."

Cruchley was too angry to see his advantage.

"Well, I like that!" he cried. "I like the idea of you posing as the injured party. Here you have made me an absolute confederate to one of the grossest frauds ever worked upon the public. Good heavens, man, when I think of the reams of gush that have been written about Miss Parlby I don't know whether to laugh or to cry."

"I don't see anything to cry about," Machin said. "I think I'm a fairly modest man, but I cannot close my eyes to the fact that in me you have presented another great literary genius to a grateful public. Dash it all, man, I did write those stories, and I did write those books. And, what's more, there will be plenty still where they came from. Of course, if you like to repudiate me and tell the whole truth, I shall be pleased to take my work elsewhere. But the public would only laugh at you and go on reading the immortal works of Laura Jane Parlby all the same. My dear chap, what are you going to do?"

Cruchley wasn't quite sure. Assuredly he would be laughed at if the story became public, and most assuredly his house would lose the benefit of Machin's work. And that it was really good work there was no denying—it seemed almost impossible to believe that this big man in the rough tweed suit was capable of such dainty fiction.

"Oh, I'd better let it go," he growled. "I must tell my proprietors, of course. And, as you say, no one has been hurt and the public has been elevated."

And Machin was quite content to let it go at that.

THE dim little courthouse was packed to suffocation. A dense mass of perspiring humanity sat there watching Archer Steadman being tried for his life. There were hundreds of people who knew him personally, they had chatted with him, shaken hands with him, asked him to their homes. They had applauded him in the cricket field, they had cheered his triumphant progress at football, Castleford had been proud of him. The sleepy old cathedral city had never produced a finer athlete. And Arthur Steadman was being tried for murder.

People remembered now that he had always been a 'bit of a waster.' His life was clean enough, but he really was a loafer. Old Gordon Steadman always said so, though he was good to his nephew in his own queer, eccentric way, and gave him some kind of allowance. Perhaps Archer had counted on dead men's shoes; certainly he had counted on having the old man's money some of these days, and there was a good deal of it, too. So Gordon Steadman had grumbled and paid till three months before when there had been a dispute over a betting account of the younger man's. And Gordon Steadman had had a perfect horror of betting. Archer had given him a promise as regarded that vice and he had broken his word.

Everybody had heard the story, of course. These things cannot be a secret in a small, cathedral city. There had been a final split, and Archer had been ordered out of his uncle's house. In future he could look to himself for his bread and cheese. He would have to earn his own living. And Archer had set out to do so fearlessly enough. At the end of a fortnight he was absolutely penniless, in debt to everybody; he was getting shabby and moody and discontented.

A week later and the startling discovery had been made that Gordon Steadman had been foully murdered in his own house in broad daylight at four o'clock in the afternoon. The victim's house was a rather lonely one on the outskirts of the town; it boasted a wonderful walled-in garden where the old man followed his favourite pursuit, the study of the ways and habits of wild birds. At the back of the house was a kind of garden-room with French windows opening on to a lawn and here Mr. Steadman passed most of the summer. At three o'clock on the day of the tragedy his housekeeper had taken him in a packet of films for photographic purposes, and at that time he had been writing at his desk. His keys lay on the table, and he had appeared to be busy. An hour later, when the housekeeper took in the usual cup of tea, she was horrified to find her master dead, his head shattered by a blow from some blunt instrument.

Whether there was anything missing nobody ever knew. Nothing appeared to have been stolen, for there were valuables in the desk. Mr. Steadman's cheque-book appeared to have vanished, but there was no significance in this, for it was just possible that at the time of his death Mr. Steadman was out of cheques altogether. The papers did not even mention the matter.