|

Project Gutenberg

Australia a treasure-trove of literature treasure found hidden with no evidence of ownership |

BROWSE the site for other works by this author (and our other authors) or SEARCH the entire site with Google Site Search |

Title: The King Who Was a King Author: H.G. Wells * A Project Gutenberg of Australia eBook * eBook No.: 1303301h.html Language: English Date first posted: Jun 2013 Most recent update: Jun 2013 This eBook was produced by Roy Glashan. Project Gutenberg of Australia eBooks are created from printed editions which are in the public domain in Australia, unless a copyright notice is included. We do NOT keep any eBooks in compliance with a particular paper edition. Copyright laws are changing all over the world. Be sure to check the copyright laws for your country before downloading or redistributing this file. This eBook is made available at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg of Australia License which may be viewed online at http://gutenberg.net.au/licence.html To contact Project Gutenberg of Australia go to http://gutenberg.net.au

GO TO Project Gutenberg Australia HOME PAGE

Wells wrote this film scenario as an effort to spread his ideas for a world state to the cinema audience. When he was unable to find a sponsor to produce the film, he converted it into this novel. The central issue is the question — Is one man justified in shedding the blood of another, in order to avert the greater catastrophe of war?

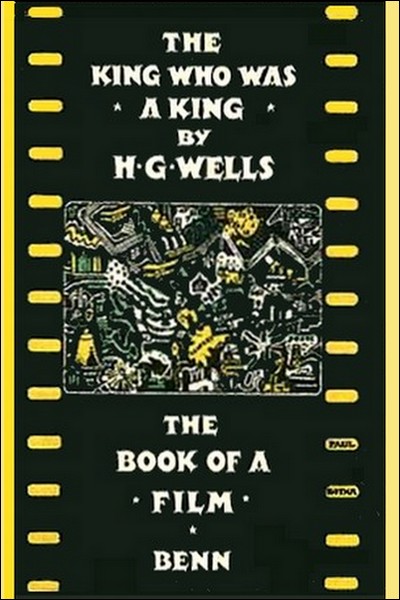

"The King Who Was a King" — British (left) and American (right) first editions

It has been interesting to watch the elegant and dignified traditions of the world of literature and cultivated appreciation, under the stresses and thrusts produced by the development of rapid photography during the past half-century. Fifty years ago not the most penetrating of prophets could have detected in the Zoetrope and the dry-plate camera the intimations of a means of expression, exceeding in force, beauty and universality any that have hitherto been available for mankind. Now that advent becomes the most obvious of probabilities.

The line of progress that was to open up those unsuspected possibilities lay through the research for more and more sensitive photographic plates, until at last a type was attained to justify the epithet “instantaneous.” Various motives stimulated such a research. The disputes of Governor Stanford of California with his sporting friends about the real paces of horses made him anxious to fix attitudes too transitory for the ordinary eye, and he was a rich man and could offer considerable inducements to the inventive. He got his inventors and his snapshots. And also working in the same direction to stimulate rapid photography there must have been a desire to put the ordinary photographers’ “sitters” more at their ease, and attempts to facilitate the operations of the amateur photographer, and so promote the sale of cameras.

The Stanford snapshots came to Paris and played an effective part in a discussion of the representation of horses in movement that raged there about Meissonier as a centre. Meissonier saw more quickly than most of us, and his representation of horses was at war with established conventions. It was Meissonier apparently who suggested the reconstruction of animal movements by running the new “instantaneous” photographs together. So in Paris Zoetrope and rapid plate met and the moving picture was born. But while the photography was done on glass the achievement remained a clumsy one. Mr. George Eastman, of the Kodak Company, hot in pursuit of the amateur photographer as a buyer of material, was the man chiefly responsible for the replacement of glass plates by a flexible film. By 1890, the “moving picture” was in existence, and the bottling-up and decanting of drama by means of film and record an established possibility. In 1895, it seems—I had completely forgotten about it until I was reminded of it by Mr. Terry Ramsaye’s history of the film—Mr. Robert W. Paul and myself had initiated a patent application for a Time Machine that anticipated most of the stock methods and devices of the screen drama.

That something more than a new method of reproducing and distributing dramatic scenes had appeared, does not seem to have been realized for some years. The films began with “actualities.” the record of more or less formal current events, and with an almost normal drama, freed only from a limitation to fixed “scenes”; and with these two items they prospered and were content for a long time.

Indeed, the idea that the film was just a way of telling stories in moving pictures dominated the cinema theatre entirely for nearly a couple of decades, and still dominates it. It satisfied a hitherto unsuspected need for visual story-telling. It worked out lucratively. The themes, the concepts, the methods that ruled in popular fiction, popular drama and the music-hall were transferred to the cinemas copiously and profitably, and with the greatest possible economy of adaptation. It would be ungracious for a novelist to complain. Through a happy term of years “world cinema rights” distended the income of every well-known novelist and playwright. The deserving class of fiction writers was enriched even by the sale of the “cinema rights” of tales quite impossible to put upon the films, rights which the purchasers, nothing loth, were willing to buy again so soon as the period of the sale had elapsed. The industry clamoured for “stories,” and its chief anxiety was that the supply of “stories” might presently come to an end. It bought right and left; it bought high and low; it was so opulent it could buy with its eyes shut. It did. Its methods were simple and direct. It took all the stories it could get, and changed all that were not absolutely intractable into one old, old story, with variations of costume, scenery and social position. That story included, almost of necessity, a treachery and a vindication, a partial rape and a pursuit. The new industry drew its actors from the stage and the music-halls and packed them off with the cameras to wherever in the sunlight the scene happened to be “laid.” We saw Carmen in a real Spanish cigarette factory, Louis XI., only slightly out of place, at Carcassonne, Les Miserables in a perfect French setting, manhood stark and strong in a hundred variations of the Blue Lagoon, and the Sheik served hot upon his native desert. The wild Far West exhausted all its stories, and fresh ones were bred from the old. They bred true to type. Unless human invention cracks under the strain of a demand for variations that do not innovate, there is no reason why this naive film-story business, real in appearance and easy and conventional in sentiment, with the punishment of bullying and treachery, the reward of sacrifice, virtue saved in the nick of time and true love coming to its own, seed time and harvest, should not continue indefinitely a staple article of consumption. And so, too, the exploitation of amusing personalities in series of well-contrived comic or humorous adventures, depends only upon the appearance of these rare gifts of God, the personalities themselves. (How rare they are! How rare and wonderful!) But more of them will be discovered, rare though they are, and the cinema will watch for and welcome them and, with a thoroughness no form of success has ever known before, embalm and cherish their memories.

Beyond these first established and permanent uses of the film, the critical and discerning few have always suspected other possibilities. I do not refer here to its obvious educational applications: a matter merely of adaptation and organization to class-room and lecture-room needs. Progress in the scholastic world is deliberate, yet there seems no reason to deny its occurrence; in a generation or so the “educational film” may have become a recognized instrument of education. But from the first it was evident that a quantity of possible cinema effects were not being utilized at all in the current methods of exploitation, and enquiring spirits sought opportunity to explore this undeveloped hinterland. It is this hinterland of real novelty that is the most interesting aspect of the cinema to-day to people who have outgrown the story-consuming stage. It may be that many of these early investigators realized little of the vastness of the region into which they were pressing. It may be that many of their earlier experiments were silly or affected. For a time, moreover, their enterprise was restrained by the huge commercial success of the commonplace quasi-realistic story. The cinema theatre was doing far too well to welcome any disturbing experiments. It would even block them. Collateral developments with a flavour of criticism and competition were not wanted.

These honest pioneers were for the most part young and unknown people, and they got little help or encouragement from those of us who had achieved any popular standing as novelists or playwrights. We had learnt our tricks and mastered the limitations of the old conditions. We were set in our careers. The magnificent marketing of our “film rights” in what we had already done, helped our willing blindness to the fact that that was not at all the sort of thing we could do for the films. It was expecting too much of us that we should hail the advent of a greater and richer artistic process. Some of us said, “This business is not for us, whatever its possibilities—if it have any possibilities—may be”; and others of us held that there was nothing here but a handmaid for the master crafts we followed. We were pre-disposed in every way to think upon such lines. Within our own special limits we had learnt to handle considerable complexes of ideas and emotional developments; it was appalling to think of learning over again the conditions of a medium. We knew how to convey much that we had to say by a woven fabric of printed words or by scene and actor, fine “lines” and preface assisting, and it was with extraordinary reluctance, if at all, that we could be won to admit that on the screen a greater depth of intimation, a more subtle and delicate fabric of suggestion, a completer beauty and power, might be possible than any our tried and trusted equipment could achieve.

Yet lying awake of nights it was possible for some of us to forget the crude, shallow trade “movies” we had seen, and to realize something of the splendour of the new powers that were coming into the hands of our happy successors. First there is the Spectacle. No limitations remain of scene, stage or arena. It may be the convolutions of a tendril which fill the picture, or the bird’s-eye view of a mountain chain, or a great city. We can pass in an instant from the infinitely great to the infinitely little. The picture may be real, realistic or conventionalized in a thousand ways; it may flow into and out of a play of “absolute” forms. And colour has become completely detachable from form. Colour in the films is no longer as it is in real life, a confusing and often unmeaning complication of vision. It can be introduced into the spectacle for effect, slowly flushing the normal black and white with glows of significant hue, chilling, intensifying, gladdening. It can be used to pick out and intensify small forms. It can play gaily or grotesquely over the scene with or without reference to the black and white forms. Sound too has become detached for the artist to use as he will. So long as it is irrelevant it can be made insignificant, or it can be brought in as a sustaining but unimportant accompaniment. Then it can gradually usurp value. The effective practical synchronizing of sound with film is plainly possible and close at hand. Then film and music will be composed together.

The spectacle will march to music, sink to silence or rise to thunder as its effects require. The incessant tiresome chatter of the drama sinks out of necessity, the recurrent exasperating “What did he say then?” When once people have been put upon the actual stage, they must talk and flap about for a certain time before they can be got rid of. Getting people on and getting them off is a vast, laborious part of dramatic technique. How it must bore playwrights! But with the film the voice may be flung in here or there, or the word may be made visible and vanish again.

Plainly we have something here that can be raised to parallelism with the greatest musical compositions; we have possibilities of a Spectacle equal to any music that has been or can be written, comprehending indeed the completest music as one of its factors. Behind the first cheap triumphs of the film to-day rises the possibility of a spectacle-music-drama, greater, more beautiful and intellectually deeper and richer than any artistic form humanity has hitherto achieved.

It may need generations of experience to work out that great possibility, but there it is, challenging creative effort. Few of us who are in the world to-day will live to see masterpieces of the new form, but the temptation to make an essay at least a little more in the direction of that hinterland than the current film, may attract even a writer past his middle years. This book is the story and description of such an excursion. It is the slightest excursion, a mere trip. Years ago the writer had a joy-ride in an aeroplane over the Medway and prophesied Lindbergh. This is the same sort of thing. We ask, Can we get off the ground of the realistic story-film? The writer discusses an imaginary film with the reader; it is a film dealing with a theme of world-wide importance. The problem to which we set ourselves here is this: Can form, story and music be brought together to present the conditions and issues of the abolition of war in a beautiful, vigorous and moving work of art, which will be well within the grasp and understanding of the ordinary film audience?

At the least the writer hopes this will prove a provocative and interesting failure. At the best it will be a producible film, marking a distinct step forward from the mere spectacle and the mere story towards an intellectual and æsthetic entertainment.

If any existing work of art is directly available as a film synopsis upon these newer lines, it is surely Thomas Hardy’s Dynasts. It is perhaps lucky for some great film corporation that I am not its director, for certainly I would at once set about realizing these marvellous stage directions, so impossible on any stage, so easy for the cinema producer with money to spend. Two I may quote by way of a sample:

“At first nothing—not even the river itself—seems to move in the panorama. But anon certain strange patches in the landscape, flexuous and riband-shaped, are discerned to be moving slowly. Only one movable object on earth is large enough to be conspicuous herefrom, and that is an army. The moving shapes are armies.”

And again:

“The nether sky opens and Europe is disclosed as a prone

and

emaciated figure.”

But alas! I have no power over any big film studio, and my rôle hitherto has been to refuse to write sketches—“synopses” they call them—of films. Until at last some years ago a certain Mr. Godal came along to me with so entertaining a suggestion that I succumbed.

He had discovered a title that he considered marketable, The Peace of the World, and, going a little in advance of accomplished reality, he had advertised this as a film ready for booking. It was a title I had already used for some war-time newspaper articles, but that was a point I did not recall until later. The response to Mr. Godal’s advertisements was so encouraging that he decided to fill up the complete void that remained after the title, and come to me with the proposal that I should write a synopsis to supply the material needed. Following several conversations and certain reassurances, for there was something about Mr. Godal that I found attractive, I sat down to sketch out that synopsis. It was very different from the present story. After reading various text-books professing to expound the whole art of writing scenarios for the films, and after an attentive study of contemporary “releases,” and with these text-books still troubling my digestion, I produced a synopsis that seemed to satisfy Mr. Godal more than it did my secret judgment. For, from the very first I mistrusted those text-books. That synopsis is merely the nucleus of what follows. Expert advice assures me that in its original form it was a practicable scheme, and I am by no means sure that expert advice will extend the same toleration to my revised and expanded effort. But I have had two years and more to think over that first draft; I have watched film possibilities with a quickened interest; all sorts of things have happened on the business side; I am told there is ample financial backing now for any production I can invent, and when I ask if I may make my scenario as difficult and expensive as I like, I am told to go ahead. So here I go ahead.

I propose to describe the film very much as one would see it on the screen, and I shall even say something of the music that would have to be written to accompany it. In effect I am going to tell the reader about a film I have evoked in an imaginary cinema theatre, and having done so, I am going to leave it to my hopeful associates to turn it into a visible reality. But first I would like to discuss some of the distinctive problems of this film and how it has seemed best to solve them. And also, before getting down to the actual camera, I will deal briefly and more generally with the sort of film this is and the conditions it has to satisfy.

In the hasty and violent disputes and asseverations that constitute the bulk of literary, dramatic and cinema criticism, certain unavoidable classifications are continually in evidence. There is a pretension in one direction to be high and fine, in another to be easy and hearty, and in another to be broad and fruitful. The common nomenclature in these matters is insufficient; High-brow and Low-brow need to be supplemented by Broad-brow. The Broad-brow is as anxious not to be “arty” as the Low-brow and as terrified of the cheap and obvious as the High-brow. His rôle is neither to disdain the current thing nor accept it, but to learn by attempting the impossible and to be content with a partial success. A film which is to have for its subject the present drive towards World Peace is as likely to be abhorrent to the High-brow as to the Low. It has to give and sustain a view and a thesis; it has to reflect upon the political side of everyone; it has to show man making war, tortured and slain by war, threatened by war and perhaps and very uncertainly able to abolish war. The High-brow will call it a tract and the Low-brow a sermon, and they will blunder together towards the exit in a violent struggle to escape with these assertions intact. The High-brow has nothing to learn and the Low-brow will learn nothing; in effect they are the same thing. They are out of this attempt. After all, the High-brow is only the Low-brow plus pretentiousness. It is the same sort of brain stood up on end. The Broad-brow remains to struggle with his immense and exciting subject.

Now the “Peace of the World,” when we come to think it over, is essentially a negative expression. In itself it means nothing except the absence of war. It is human life with war taken out of it. The substantial thing therefore that we have to deal with in this film is war, as an evil thing experienced, as an evil thing threatening to recur, as an evil thing conceivably made impossible. Peace, we repeat, is simply what life is and may become as this shadow lifts. Our subject, therefore, is life overcast, but with the possibility that it may cease to be overcast, and the development of the will and power to thrust back and dispel this cloud. So necessarily we have three main strands to supply the threads of interest in our film: first, the lovely and splendid possibilities of life, relieved of the restraints and destruction of war; next, the dark actualities that destroy life in warfare itself, and cripple and enslave it monstrously in the anticipation of war; and thirdly, the will to end war. This last is the heroic element. The story of the film must be the story of heroic service, of Hercules, if we are to carry the struggle to an imagined triumph; of Prometheus, if we are to go no further than a phase of revolt, initial defeat and the promise of a remoter victory. I have chosen for this experiment to take the simpler and more glorious path, because I believe that there can and will be an end of war. In this film the defeat of war by the will of man is to be shown in progress. Man’s will here is to be cast as demi-god and not as Hamlet. The spectacle is to be this present age seen as the Age of War Drawing to an End, and the human beings in the foreground must embody the hopes, fears, effort and success of a struggle that approaches a triumphant close.

In the opening survey of the material that presents itself, various methods of treatment had to be considered. Should we embody the forces at work in individualities and make the personal drama of some pacificist person or group our thread and chief sustaining interest, or should we make a film entirely spectacular, in which the onset and avoidance of war alike would be treated as mass phenomena, with waving flags, crowded streets, cheering multitudes, skirmishes, battles, war incidents, the hunting down and shooting of a protesting pacificist, the desolation of a home by a telegram, the recoil of young heroes from warfare, peace discussions, protests, mutinies, cabinet councils, international conferences and so forth, making together a vast heterogeneous procession from excitement to tragedy, fatigue and reaction? The latter of these two ways of treatment would be very much on the structural lines of that great unshot film, the Dynasts; the former would bring us much nearer the normal film story. It would be a normal film story with a relatively greatly enhanced and deepened spectacular background. The wall of the room would have to dissolve and show the world threatened by air, sea and land, but it would close again to resume the personal experience. The entirely spectacular way would certainly be nearer the truth, for the end of war is only possible through the convergent activities of thousands of different movements, propagandas, efforts and struggles. But it would make our film vie in scope and confusedness with the spectacle of life itself.

Little films must come before big ones and in the end it was decided to take the first of our two alternatives, and concentrate upon an individual figure in the foreground to unify all that we had to convey. The material would be too various, limitless and incoherent, unless there was this resort to a human being or a group of interacting human beings, responding to it all and trying to apprehend it all, as a bond of continuity. Undramatic entirely plotless spectacular films have, it is true, been made already and have proved enormously effective; that magnificent production, Berlin, for example. Some day again the great war of 1914-18 may be drawn together into one tremendous impersonal vision; but both these subjects possess an established organic integrity. The audience knows already that the parts belong to one another. Our subject, on the other hand, is an exploration and a synthesis that has to be established. What we have to present has not been established. To establish it and secure conviction in the audience, the manifest expedient is to show conviction arising in a sympathetic mind. A hero has to be invented to embody the will to abolish war in the audience, a hero who will concentrate the problem of what has to be done into a personal and understandable problem.

A hero here means an immense economy in statement. Art broadly conceived may be regarded as an attempt to simplify statement quite parallel to the attempt of science to do the same thing. But while science makes an intellectual synthesis and simplification, art’s synthesis and simplification are æsthetic. Intellectual processes are generalized processes common to all; but æsthetic processes involve someone who feels, and the method of art therefore has been always towards personification and the appeal of art towards sympathy. But a casually selected individual will not serve for our personification here. He must be exceptionally representative. The forces making for war must converge upon him; he must be in a position to make effective decisions for or against war. The spectacle of war-possibilities can then be unfolded in relation to his thoughts and acts. New war devices can be brought to him, he can listen to war schemes and have peculiar opportunity to see war approaching and understand what it will be like; his mind must translate these intimations into terms of human apprehension, judgment and endeavour. He will think out and carry out a course of action which must be a typical course of action. So he can be at once himself, and crystallize that intelligent will against war which is diffused so widely throughout contemporary humanity.

In spite of the present world-wide trend towards republican forms, it is structurally very convenient that this hero should be a monarch. Manifestly he has to be a very idealized monarch, a kingly concentration of the kingly will in all of us rather than a normal king. He will not be the sort of king who takes refuge behind a dictator or accepts the position of a petted symbol; he will think and act as a responsible ruler. This means that he will have escaped the normal training of a modern royalty in tact and apt graciousness, and that he takes kingship in naive good faith. He is, in fact, to be the common intelligent man as king. He is to be the king in you and me.

The best way to contrive that seemed to be to make him the son of a prince of some royal house who has gone into exile in America—as princes have done—and to make the Great War and some sudden catastrophe kill off the intervening heirs and clear his way to a Crown. This is a fairly obvious way to our end. In America his father, we assume, has dropped his titles, and he himself, unencumbered by any court tutoring, has read and assimilated the most modern and progressive ideas. Then if the kingdom to which he is suddenly projected is one of those crucial minor states where Europe, Asia and American enterprise meet and the great economic interests and national policies of the world jostle against each other, we shall have brought to a focus all the main factors in our discussion in a very convenient form. The jostling, we may suppose, is drawing to a crisis at his accession.

What will this King Everyman, who is really a concentration of hundreds of committees, thousands of leaders and millions of mute followers, do about it? Just so far as he is man enough and king enough the problems of the Peace of the World and the problems of his personal adventure become one.

Manifestly this highly generalized man, our hero, must be a good-looking, able-bodied, thoughtful person, not so much the average man as the quintessential man. His individuality must lie in his ready understanding and his abnormal steadfastness of will. Impossible here to give him “character” as it is commonly understood, oddity or idiosyncrasy, wooden-leg, wig, glass eye or inferiority complex. These things belong to another type of story altogether, very moving and appealing, but far away from this one, the story of individual limitation and its comedy and tragedy. Our hero is to be a man without frustrations. He is to be yourself and myself as we would like to be, simplified, clear in his mind, unencumbered and going directly to his objective.

The film entrepreneur having given his imaginative author carte blanche is apt to return upon his tracks with after-thoughts. Among the trade and professional solicitudes that haunt him, one is predominant. He has to secure the services of a starry lady. More than half the normal audience is feminine. He insists they must find themselves in the film, and from his point of view this can only be done by introducing a “love interest.” Our hero must have his sufficiently difficult task further complicated by the dire attractiveness of blue eyes or brown—or both. It is necessary that this delusion of the film entrepreneur should be dealt with plainly. A normal love interest has to be kept out of this film. It will be either a triviality or a fatal interruption.

By a normal love interest I mean the story of a man strongly attracted by a woman, or vice versa, and the success or failure of a sustained effort to possess her, the price paid and the good or bad delivery. This is currently assumed to be the chief motive in human life, and certainly it is that in the conventional film story. It is supposed to be particularly satisfactory to woman that life should be presented as sexual to this degree. No doubt sexual attraction is a very vivid motive at certain phases of most of our lives, but it is not the sustained or prevalent motive in the lives of most men, nor do I believe it is very much more important to women. Tradition and social conditions make the lives of most women turn more upon a sex affair than do the lives of most men, and there may be a greater constitutional predisposition in them towards sex issues. But there is surely not that absorption this incessant demand for a “love interest” implies. Women can listen to sexless music and compose and play sexless music; they can do scientific research, produce art and literature, give themselves to sport or business, without even as much direct sex obsession as many men betray. It is, however, not quite so certain that they can lose sight of their own personalities as completely as men can do. If women are no more sexual than men, it is nevertheless open to question whether they can release themselves as readily from a personal reference. My own impression is that, typically, they see the rôle more and the play less.

Now, first, with regard to this film I am convinced there can be no love interest, no chase and capture, of the vulgar sort. I would lay it down as a general rule that a love interest of the normal type in a film, novel, play or any other form of story conflicts with any other form of interest, and either destroys it or is itself reduced to the level of a tiresome complication. I have had a certain experience in the writing of wonder stories, romances about some sort of wonder, a visit to the moon, for example, the power of invisibility, the release of atomic energy for mechanical purposes or the like, and nothing is more firmly established in my mind than that these topics can only be successfully dealt with by the completest subordination of normal sex adventure. Hundreds of failures in that line are due to the neglect of this simple prohibition. Either Juliet must have all the stage and limelight, or Juliet (with her Romeo) is merely obstructing the traffic. That is the law of it. The world grows out of the amiable delusion that Juliet (or Romeo) can be an “inspiration” for anything in the other sex except a strong desire for her (or his) charming self. Our hero wants to end war on its merits. It is no more conceivable that he sets out to end war for a woman, than that he does it for a bet or because some other fellow said he couldn’t.

The entrepreneur of this film therefore must deduct from his calculations all that much of feminine humanity which insists upon pictures in which, as a primary element, it is, by sympathetic proxy, desired, adored, wooed, chased, trapped, rescued, dressed up, dressed down, undressed and finally and thumpingly won and made to yield deliciously and completely. That proportion of women will stay away. That proportion of young manhood too which finds its secret wishes embodied in the successful desiring, adoring, wooing, chasing, trapping, rescuing, winning and conquest of the delicious heroine must also be counted off. Perhaps we underrate the last contingent and overrate the proportion of feminine supporters of the dominant “love interest.” And certainly our repudiation of the “love interest” by no means implies that the entire feminine sex is excluded from this film or that no appeal is made in it to the consciously feminine element in the audience. It is not merely that it is put to them how, as human beings, they are going to share in the Herculean task of cleaning up all that now festers towards a renewal of war, but also and more intimately whether, as women, with woman’s acuter sense of rôle and keener perception of personal values, they have not a very special part to play in the struggle.

And here we must raise a question that is always cropping up in myriads of actual instances in modern life: Do women to any large extent and in any number really want the organized prevention of war? Just as one questions whether they want a mighty growth of science? Or want a world rebuilt on greater lines? Indignant feminine voices, quick to resent an implied belittlement, will retort at once, “Of course they do. Are they not the mothers and wives of the men who must be killed? Is it not their children and their homes that suffer most acutely from conflict and disorder?” But it is just that sort of reply which intensified the doubt. These are reasons why women should want an end to war, but not any proof that they do or are at all disposed to set about helping to end it for its own sake. Many men, although they are the fathers and friends of the men who must be killed and themselves must share the toil and risk, want peace and a reorganization of the world’s affairs without any thought or very little thought of this personal aspect. They see war as a nuisance and an offence upon the general field of human work. They see spoilt possibilities in which they themselves may have only a very slight personal share. War to them is a monstrous silly ugly beast that tramples the crops —a beast which may yet give good sport in the hunting. It is hated not as a horror but as an appalling bore. And the soldier is regarded not as heroic-terrible but as a tedious fool. Is there any equivalent proportion of women who see things in this way?

We have to frame some sort of answer to this before we can decide upon the part women are to play in this film. Is there to be a sort of feminine twin to Hercules in this film? A heroine parallel to the hero, profile to profile, like William and Mary on the old pennies? Or contrariwise, is woman to play the part of Deianira and cajole the hero into the shirt of Nessus and ultimate frustration? We have told that last story so often; we have had to tell that last story so often. It is one of the endlessly repeated stories, that story of the woman sex-centred, who wants so to concentrate the love of a man upon herself that she destroys him. But is it as usual to-day as it was in the past? Is this mutual injury through the egotism of love an incidental or an inevitable part of the human adventure?

And anyhow, since we have decided that this shall be a film of present victory and not defeat, even if Deianira is to appear, she will have to be evaded or defeated. Nessus’ shirt can go back to the property room; it will not be worn. But it does not follow that parallelism of the sexes is the only other course. If women are going to play the same part in regard to war as men do, what need is there for a separate woman part at all? Fuse her with Hercules and let the film be sexless.

The reality lies between these contrasts. The liberations of our time release women more and more from the sense that custom, training and tradition have imposed upon them, of the supreme necessity of capturing and holding a particular man. But these liberations do nothing to change the essential fact that women do see life much more acutely as an affair of personalities than men do. They too are escaping from submersion in the personal drama, but they do not seem to have escaped to the same degree. They have the power to intensify the sense of individuality in men. They are apter to judge and readier to take sides, and when they take sides they do it with less limitation and compromise. In the vast and complex struggles that lie before us if the world is to be organized against war, women will be mainly assessors and sustainers. In this heroic endeavour to evolve a rationalized world out of a sanguinary confusion of romantic falsehood which is our present theme, just as in the struggle to establish social and economic justice, women will be decisive. Just so far as they give their friendship, encouragement, social support, their enormous powers of conviction and personal reassurance, to the struggling (and often doubting) spirits of creative men, so far will they enable them to realize effort. Just as far as they are dominated by the thought of their own individual triumph, just so far as they subordinate life to the conception of themselves as beloved individuals, queens of beauty, and the chief end of life to the old romantic conception of the egoistic love interest as the supreme interest for women, so far will they be on the side of the antagonists against the hero.

Our chief feminine interest therefore presents itself almost inevitably in two aspects, two parts: the first, the woman as disinterested friend and sympathiser; the second, as woman the decisive, emerging from the romantic tradition, attempting to make a personal lover of our Hercules and then realizing the greater power and beauty of his larger and ampler purpose, giving herself to that and gaining herself, him and everything in that self-subordination. This second aspect is manifestly the more dramatic one, and it gives us the indications for our main feminine rôle.

For the uses of our personified story she can be a Princess, the effective ruler of another State close to the hero’s and strategically essential. She apprehends the fine quality of his purpose and his endeavour, she tries to conquer him for herself, she becomes his fierce, and for a time she seems to be his chief antagonist, and then swiftly and decisively she becomes his ally and mate. Like the hero she must be simplified beyond any vividness of characterization; she must be beautiful, vigorous and direct. The frustrations of individuality are all on the other side in this film.

We have now given the reasons for making the hero and heroine in the story-argument of this film grave, abstract, quintessential and symbolical. For the antagonisms they face this is not nearly so necessary. It is just because the mind has to be left free to consider the complex of forces that make for war and keep it alive in the world, that these tremendous simplifications on our side have been made. For that we have resisted the temptation to make our hero “sympathetic” by, for example, giving him funny feet or a fascinated devotion to our heroine’s crisp naiveté. The adverse forces, however, we suppose to be working through the weaknesses and intricacy of human nature and the errors in and distortions of human tradition. Our thesis is not that war is a simple thing but a muddle, an Augean stable to be cleaned up. The rest of our cast therefore can be a multitude of highly individualized figures, all with good and bad in them—all, so to speak, with souls to be saved.

Yet something is common to them all and holds them all together so that they are not an aimless miscellany. They are all susceptible to war suggestion. There is that in them which responds to war suggestion, a complex of fear, suspicion, self-assertion, gregarious assertion, xenophobia, pugnacity and subtler correlatives. War possibility is due not merely to ignoble strains in them. Brotherhood, loyalty, love of the near and intimate and fear for its security, the impulse to give oneself, may be played upon also to bring them into the bloody work. We have to show them under that complex of good and evil dispositions, and we have to show them diversely and humanly, so that the audience may find material for self-identification on that side also of the argument. But taken altogether we allege that there is an evil disposition inspiring that diverse antagonist mass. Against man the maker, man the hater, man the enemy of man, pits himself, more primordial, narrower, intenser.

Suppose we take a leaf from the book of the medieval moralist, who went so frankly outside his proper Christian theology to hypothesize a devil. Suppose we make an antagonist to our hero, a spirit of jealousy and narrow aggression flitting through our film, inspiring this man, taking possession of that, sowing the tares, blighting the harvest. What sort of figure will he be? I conceive of him as something quite unlike that dithering devil Mephistopheles, who played so large a part in the moral symbolism of the nineteenth century. He will be much more an upstanding figure, more of a combatant and nothing of a mocker. Both he and the hero are fighters; the difference is that he is dark, narrow and destructive, while the hero fights to create. It will be false to refuse him a dark splendour, a beauty of his own. Neither is passive. They are kindred in that, and so we must admit a sort of likeness between the two, a cousinship. He hates. Through the ages he has been the inveterate enemy of the broad purpose and the distant aim, and the pitiless exploiter of that mingling of love and timidity in us which makes us all apologists and defenders of the accustomed and the limited.

So out of the proposition implicit in that original title of ours, The Peace of the World, we evolve the characteristics of our protagonists and antagonist. Quite after the most respected traditions of the movies, we drop our original title, and substitute, The King who was a King. We have now to develop the concrete story of King Everyman, the Princess and his Cousin the Destroyer, keeping in mind continually the great arguments they sustain.

The ordinary film to-day opens very raggedly, with unmeaning decorations and distracting irrelevant matter. I would reduce and simplify all this preliminary stuff as much as possible. For example there is the long list it is customary to give of the names of people who have contributed to the making of the film. Few of them are known well enough to arouse serious expectation or prepare the mind of the audience in any way, and all this and the advertisement of the entrepreneurs, the animated trade-marks and so on, would be better deferred until the end, when the audience is grateful for and excited by its entertainment and anxious to know whom it has to thank. I would begin starkly with a black screen with the title in very plain clear lettering (no “art” distortion),

THE KING WHO WAS A KING

This should be held for rather a long time in silence, still and important.

Then would come the title and the sub-title, arousing expectation,

THE KING WHO WAS A KING

THE STORY OF A PAWN WHO WOULD NOT PLAY THE GAME

That too would have a pause. Then I would have the music begin and the title fade out and give place to a slow drift across the screen, like a drift of sunflecks under trees ("absolute film” as the current phrase goes), keeping time to the music. The music would be threaded more and more with a rhythmic tapping and clinking, and the drift would eddy and swirl away and display a squatting half-brutish figure in a vague dark cavern, a primordial savage chipping a flint.

He would be the forerunner both of the hero and antagonist. He would change imperceptibly from the half-bestial into the human and he would presently be hammering a metal implement upon an anvil. He would put it aside to take up a carving. The lettering, “Man the Maker,” would appear above him and fade out again. Beside him the premonition of the heroine would appear: woman. He would show his work to her, valuing her approval. Then he would become a duplicated superimposed figure, and the two figures would separate. Man the Maker would remain seated at his work with the woman looking at him, while the second figure would stand away from him and over him, looking at him and the woman. Lettering would appear against the cavernous darkness above this new aspect of man, Man the Destroyer, and fade again.

The Destroyer is jealous and hard. He covets the woman simply and hates the Maker’s work that interests her. He stoops down to seize the spear the Maker has shaped, and raises it as if he would threaten and dominate Man the Maker. The Maker leaps to his feet to regain possession of it. There is a struggle. One sees the two muscular bodies at grips and the stern faces close together. The Destroyer holds the spear; the Maker grips the Destroyer’s wrist. The woman watches and her movements are indecisive. She lifts her hands as if to intervene, the music rises and dies away, the cavern grows dark, the struggling figures indistinct, and the streaming flecks of light return out of nothingness, drifting across the screen again. They fade out to a blank darkness as the music fades also. The argument has been stated and the story can now begin.

The world appears upon the screen rotating slowly, and a new movement of the music differing widely in character from the preceding one, music with a marching, militant quality, drum taps and trumpet airs, begins but dies away to the quality of an unimportant accompaniment. The world grows larger and the familiar outline of the Western hemisphere comes round to the audience. The globe sweeps towards the audience until North America fills the screen, a hand appears and points to New York, and a characteristic view of New York, an aeroplane view, is superimposed upon the screen as the hand (grown large) is withdrawn. This view recedes and a window-frame about it becomes visible. We are in the intimate conference-room of a great business organization in lower New York. A table, with fresh paper, etc., is prepared for a meeting.

The room can be rotated to make the window invisible or unimportant (the view has served its purpose). The room has two occupants. A man, A., of the ordinary successful business-man type, with a face of quiet determination, is fixing a map to a display board with drawing-pins. An office attendant stands by with the box of pins.

The map is important and the attention of the audience is concentrated upon it.

The map is to be a bold revision of all known geography. It must be prepared by a competent cartographer, as though it was a real standard map. It must not be a sketch map. It shows a broad seaway narrowing to a long and winding strait and then broadening out again into a sea rather like the Black Sea. The strait and all the surrounding country is marked KINGDOM OF CLAVERY. Behind it, in mountainous country and quite cut off from the sea, is the REPUBLIC OF AGRAVIA. To the west and partly enveloping the eastern end of this is SÆVIA, also mountainous, which bars the access of Agravia to the inland sea. Behind Agravia to the north is a boundary and the end of a name which is not wholly on the map, one or two letters being cut in half. The audience reads SSIA. Occupying the south-west of the map is the-IAN SEA. An island or so.

Now here we use colour. The attendant holds out a bottle of ink, and A. has a ruler and a quill pen. He dips the pen in the ink, makes spots on the map and rules lines which appear in bright red. Then he writes in the margin of the map: “Red indicates chief calcomite deposits.” They are all in Agravia except one, which overlaps into Sævia.

As he does this a second business man, B., enters the room and surveys the work.

“There,” says A., “are the only deposits of calcomite in the world that are not in British territory.”

B. reflects. “Who could have foretold ten years ago that all our metallurgical industries would depend upon this one rare mineral calcomite?”

A third business magnate joins them.

“Most of the country,” says A., “is claimed by Sævia. It was given to Agravia by the Treaty of Versailles.”

Other members of the Conference arrive. They go to the table and then are drawn to the discussion about the map. A. is obviously the best informed man in the gathering. He explains: “The Agravians are a nation of farmers. They do not want their minerals exploited.”

This stays on the screen for three or four seconds and then these words are added: “Naturally the British support them in that attitude.”

These words are uttered by a newcomer, C., who is impersonated by the same actor as Man the Destroyer in the prelude.

His words seem to change the key of the conversation. The other men turn their backs upon the map and move towards the table, where he stands one foot on a chair and forms the centre of the assembly. These sentences appear one after the other upon the screen as if spoken slowly, with pauses between. Then they are all held assembled for a moment.

“Sævia is too weak to attack Agravia.”

“But with Clavery to help, it would be a different story.”

“We have some good friends in Clavery.”

A seated man with an impassive face remarks:

“To-day is the birthday of the King of Clavery, and to-day, as we talk here, the Princess of Sævia is being betrothed to the Crown Prince of Clavery.”

“And then?”

C. speaks: “Agravia has no guns nor aeroplanes worth talking about. The army of Clavery is small but good. It would scarcely be a war.”

But it is evident that the Conference still doubts. A., perceiving the hesitation, returns to his map and taps it as he speaks.

“Free access to this calcomite means for America liberation from this stranglehold upon our metallurgy that luck has given the British.”

The group of men regard A. as he says this. The broad stripes of the American flag wave softly across the picture. But they are doubtful if the thing can be done so easily. Then for a moment a Union Jack, stiff in the breeze, is flashed on the screen. Then C. says, “The British are too fond of blockades and strangleholds.”

There is a vision of a British Fleet steaming along some blockade coast, and then this fades out to be replaced by a great American battleship, flags flying and coming full speed ahead towards the audience, which fades also to show the Conference, ruffled, uneasy, perplexed. A little capable-looking man, D., says:

“Why should two great Powers quarrel like this? Why should we not work with the British?”

This question and reply are thrown on the screen in white.

“Always?”

“Yes, always.”

C. protests.

“The next thing you will want will be a permanent reunion with the British! What is the good of having different governments and different flags if we are always going to work together? Why have a flag if it means nothing?”

The little man D., driven to extremes by the argument, gestures “Exactly; why have it?”

Everyone is interested and a vivid discussion ensues.

And here we appeal to the powers of suggestion inherent in the film. The complex that renders any idea of amalgamating American interests with those of any other Power, and particularly with those of the British Empire, impossible, exists in every mind present in the conference. The organized peace of the world is distasteful because the Union is so dear. Through all this whirl of thought and feeling run the waving stripes of the American flag, surely the most beautiful on earth; and the musical accompaniment, which was scarcely perceptible in the opening of this scene when A. was marking calcomite on the map, becomes now the inspiring intervening memories of patriotic music. The audience is given dreamlike glimpses of pages from American history, if possible from well-known pictures: the bridge at Concord, the battle of Lexington, Valley Forge, etc. The British soldiers march on Washington and the capital is seen burning. The Shannon and the Chesapeake fight. The figure of George Washington rides up the scene, dominates it, mingles with the Star-Spangled Banner and fades out. You never quite lose the talking men as these visions expand and pass.

The little man D. is seen standing up and still clinging to his argument.

C. interrupts him. These sentences are thrown across the picture:

“Something we don’t like in the British.”

“Arrogance.”

“We’ve sat quiet under their Fleet for a century.”

A. says with violence: “Yes, but our turn has come.”

The great American battleship reappears very gloriously, and its guns are fired as it sweeps towards the audience. The sea-waves and the undulations of the American flag mingle together.

A man who has not spoken hitherto interrupts.

“Gentlemen, what have we got to? We were talking of calcomite? What possesses us?”

The phantom flag still waves and streams across the picture.

The discussion is interrupted by the entry of a tall man, E.—evidently a very important personality. The flag suggestion fades quite out and attention concentrates on this man. The picture darkens in its values; and grows hard and bright. He comes forward portentously with the telegram in his hand. The disputants, who have been in various easy attitudes, all stand. Then this legend is delivered on the screen very slowly, line by line:

“Gentlemen, everything has gone to pieces.

“That betrothal and the alliance of Clavery and Sævia have been blown to bits.

“A bomb in the Cathedral of Clavopolis.

“The Crown Prince is dying, the King is dead.

“You have been”—the last word is held back for a second or so—“out-manoeuvred.”

Someone asks: “And the Princess?”

“She had not arrived.”

D. cries: “The British could not do a thing like that!” The others doubt with him or scoff at him. C. is the chief scoffer.

A. says: “But how does this leave us?”

Scene fades out under his note of interrogation.

A glimpse is given of the House of Parliament and Whitehall, and then the scene is taken into a room in the Foreign Office. The time is the late afternoon. The dignified Georgian furniture of this apartment contrasts with the clear modernity of the New York conference-room. The Royal Arms and a sheaf of Union Jacks surmount a mirror at the back. A Foreign Secretary, a tall, handsome man, distinctively of the “English gentleman” type, a compendium of Grey, Curzon and Chamberlain, with if anything a preponderance of Grey, sits and examines a map. A short, very intelligent-looking private secretary stands behind him and points out the position of the States concerned. The Foreign Secretary taps the map with his glasses and shakes his head. He drops out these comments:

“I never liked this betrothal business.

“We’ve got to stand by Agravia. We’ve given our assurances.

“Ugly business.”

He continues to shake his head. Words appear across this scene exactly as they did in the preceding one.

“Something I don’t like in the Americans.

“Since the war they’ve got arrogant.

“Threatening to outbuild our Fleet!

“Vital for us. Just a luxury for them.”

The secretary smiles slightly at these almost petulant comments. He puts his hand over his mouth as if doubting the wisdom of any comment, and then decides to speak.

“Since this calcomite process came in, Sir, we have rather PRESSED our advantage.”

The Foreign Secretary does not like the matter put in that way. His gesture shows his repudiation. “Question of business” appears across back of picture. The secretary indicates by a shrug of the shoulders that it is not his place to argue.

The Foreign Secretary looks up. Someone has entered the room. He stands up. The Prime Minister appears from the side with a sheet of paper in his hand. In appearance he is to be a mixture of the last four British Prime Ministers, a generalised British Prime Minister. If any ingredient prevails it should be Mr. Lloyd George. He holds out the document. Both stand while the Foreign Secretary reads.

“The bomb seems to have killed about thirty people.”

They regard each other gravely and glance at the private secretary. The Foreign Secretary hands the paper to him. He reads and says:

“This alters the calcomite situation, Sir.”

The Prime Minister sits down. He has vital things to ask. The Foreign Secretary intimates to the private secretary he is not wanted and sits down too. The two chiefs are close together and their manner is confidential. They watch the private secretary depart.

The Prime Minister asks:

“There was American influence behind the betrothal?”

The Foreign Secretary intimates “Undoubtedly.” He makes some explanation not screened. The Prime Minister is preoccupied by another thought.

“This feeling of rivalry between us and America seems incurable,” he laments.

Both nod their heads. Then the Foreign Secretary grows bright.

“So far as regards calcomite we have had rather the best of the game.”

The Prime Minister sits back. He is uneasy. He takes up the dispatch, looks at it, and puts it down. He has a very disagreeable and searching question to put.

“Our hands are clean in this business?” he asks.

The Foreign Secretary shows two spotless hands. The two men still watch each other. The Foreign Secretary alters his attitude, plays with a blotter, considers.

“No country that carries on a set Policy against another country has perfectly clean hands.”

The Prime Minister admits that sadly. The Foreign Secretary watches him and remarks: “Every country employs spies.”

The Prime Minister knows that, but he hates to hear it.

“Every country,” the Foreign Secretary pursues, “has Agents. And Agents may employ other Agents.”

The Prime Minister wants to have that explained further. He is uneasy. He rather overdoes his innocence. Over their heads appears:

“Agents may exceed their instructions.”

The Foreign Secretary remarks: “When I was a boy at Templedale we used to play a game called Russian Scandal. Do you know it?”

He explains. The screen shows a row of young people in evening-dress sitting round a fire. The first whispers to the second, who whispers to the third, and so on. The whispers appear in white letters above each couple in succession and remain.

Canada is in America. Can a dove be in America? Can a dive be in America? Can a devil be in a merry cur? Can a devil be in a merry cove?

You see the words in white pass from one whisperer to another.

And so—

Another row of figures appears, showing a dignified Foreign Minister at one end and a chain of agents, officers, secret-service people, foreign agents, Agravian peasants.

The words, Spirited Policy, appear at one end and vanish, and the players whisper from one to another. The end man of the chain hesitates, nods, draws a knife, stands up and cries: “Murder!”

The Foreign Secretary urbane, saying this to illustrate his point. The Prime Minister dismayed. The Foreign Secretary is imperturbable. The Prime Minister shakes his head in repudiation.

The Prime Minister: “But now what happens? What is the good of it all? Who is the heir of Clavery?”

The Foreign Secretary: “There is a certain Prince Michael.”

Prime Minister: “Who may marry the Princess of Sævia and carry out the American scheme quite as well as the Crown Prince.”

Foreign Secretary, thoughtfully: “Yes. But there was also a certain brother of the late King who ran away to America on account of some lady, and left a son. He would come before this Michael.”

The Prime Minister stares at his colleague as if to discover how long he has had this fact in mind. Then he considers it for its own sake. A possible aspect occurs to him. He remarks: “Unless his father was cut out of the succession.”

The Foreign Secretary intimates that this was not the case. The Prime Minister would like to know more. The Foreign Secretary manifestly does know more. He comes to a point that is of great interest to him.

“He is an extreme pacifist. He goes about with the daughter of that pacifist fellow Harting. I have made some enquiries.”

The Prime Minister sits and drums with his fingers on the table. As he does so a line of phantom battleships passes slowly across the picture, mere shadows at first and then more plainly.

“Why do we and the Americans play this everlasting fools’ game against each other?”

Still pursuing his reflections:

“The country isn’t with us in this.

“THEIR people don’t want it.”

The Foreign Secretary considers these revolutionary remarks. They jar with his fundamental convictions. The Royal Arms and the sheaf of Union Jacks behind him grow more distinct and larger. The idea of British policy becomes visible about him. He and the Prime Minister become mere shadows through which the idea displays itself. On either side Grenadier buglers blow the bugles of empire. Then a long line of phantom soldiers in khaki advances, and behind them one sees great cities with minarets, eastern ports, elephants, the Himalayas, Australians and kangaroos, a mounted man on an ostrich farm, the crude bright elements of the pageant of British power. These phantoms strengthen and fade again. A Union Jack flutters across the screen and fades. The music swells proudly to Rule Britannia. The Foreign Secretary reappears upon the screen protesting to the Prime Minister.

“Why are we a separate Empire? Why are there such things as Powers? Why have we a Foreign Office?—if there is no game to be played—if ’Rule Britannia’ means nothing?”

The Prime Minister nods as if to say, “Yes, yes—of course.” Then he turns away, perplexed and foreboding. That standing preoccupation of party leaders appears above his head, “The country isn’t with us nowadays in this sort of thing.” He purses his lips and nods his head.

The scene fades out on his puzzled countenance, and the second movement of the music comes to an end.

A third movement of the music begins. An air already rendered in the tapping and clinking of the Prelude reappears, strengthened and bolder. At the same time rotating wheels and machine tools at work become visible. The screen takes the audience through a great factory in which the mass production of automobiles is in progress. The picturing of the factory must be good and exciting, for it is an integral part of our effects. The music must swing into the rhythm of modern machinery.

The hero, Paul Zelinka, is discovered in workman’s overalls at work. He is the same actor as Man the Maker in the Prelude. He is gravely intent upon his work. It is team work. He has to take a part from a fellow-worker, manipulate it and hand it on. He is obviously chief of the group and is directing the group task. Here he may repeat poses and gestures of Man the Maker in the Introductory Scene. The viewpoint recedes slightly to show the whole bunch of workers. They are to be the most contrasted specimens possible of the American worker—an Italian, a mongoloid Finn, a negro, a big East European Jew, and so forth. They work together methodically and quickly.

Then the viewpoint moves back until these are only small figures in a great scene of industrial activity.

Four or five men walk across the foreground. They are visitors being shown the works, and a director and an assistant. The director says:

“The man working over there is Prince Zelinka. Three lives from the throne of Clavery. The press-men have just got hold of it. We didn’t know it when he came here.”

We then get the director’s face closer. He feels he has said something snobbish and adds to correct the impression:

“On our pay-sheets he’s plain Paul Zelinka.

“Here he’s not a prince; he’s a man.”

We then get the interested faces of the whole group.

“His father made good as a working man. He has a bit of capital and he means to learn business from the bottom up.”

Then a factory whistle blows and we see men ceasing work. Zelinka knocks off and he is joined by an acquaintance, Atkins. The acquaintance, Atkins, is a small inferior type with an inquisitive face. They pass across scene to change their working overalls for ordinary clothing.

Then the scene changes, and we see Zelinka and Atkins going home from the day’s work against a background of busy American town life.

Atkins speaks:

“What’s all this talk I hear about your being a Prince or a Grand Duke or something? Anything in it?”

Zelinka shrugs shoulders as if indisposed to reply. Then thinks better of it.

“Nothing that matters. My father was a Grand Duke. Seven brothers older than himself—the war cleared most of them off. Not a very grand Grand Duke. And it bored him. There was some trouble about his marriage. She was a noble lady all right, but she wasn’t the noble lady they intended him to marry.”

Zelinka’s face becomes reflective. An interlude gives the fairly obvious tale of his father, and gives it in the manner of a score of pre-existing films.

(Zelinka’s father must be played by the same actor as Zelinka. He must make up as a more decided blond, and with a fuller moustache, pointed at first and normal later. He must do all that is possible to get a taller effect, and he might wear stays to sustain a more “drilled” bearing.)

We are given a garden terrace of the palace of Clavopolis, the capital of Clavery. It is a scene we shall see again later. Flowers. Blossom. Zelinka’s father is shown as a young man, with a fragile little wife. Costume of 1904. They talk rather anxiously. A court official comes with a summons. Zelinka’s father obeys with evident reluctance. He turns back and embraces wife.

Then comes a dignified room in the Clavopolis Palace, with a venerable monarch in military uniform seated. Court officials are grouped and waiting. A pause of expectation. Zelinka’s father enters. The King receives him coldly and admonishes him with evident severity. Zelinka’s father stands sulkily under the admonition. He shakes his head in refusal. The admonition becomes a scolding. Against all etiquette he answers back. An angry dispute follows. The old monarch orders his son’s arrest. He is arrested.

Then an escape from prison and a flight to America are indicated by three or four swift pictures.

The audience is given brief scenes of (for example) the launch leaving the liner for Ellis Island or of the young fugitives passing through Ellis Island or passports being scrutinized. Then the passage from Ellis Island to New York. The mother is seen dying in a cheap lodging (costume, 1905) and the father is doing any sort of hard industrial work the producer finds it convenient to shoot.

Then father and little Paul (five years old) tramping a long road (1910).

Then the father in working overalls in his own garage repairing a 1912 car (1912 costume). Later, the father is more prosperous in an office looking out upon some works. His manner suggests active business responsibility. Some subordinate takes directions from him. Paul, a boy of nine, comes in (1914).

These story-pictures thin and fade out to show three-quarter lengths of Zelinka and Atkins walking along the evening street again. Zelinka looks ahead and tells his story. Atkins takes it all in with a rat-like alertness.

Zelinka says: “It was only at my father’s death that I learnt my proper name and the story of his life.”

He ceases to speak and the screen shows his memory. He is now about sixteen years old, turning over his father’s papers beside his death-bed. Pause as he looks at his father’s still face. He glances round rather guiltily, as if ashamed of emotion, and then kisses his father’s forehead.

This scene does not fade out, it flashes out and gives place to:

“Well, here I am,” in white letters, and then in normal black on white—“starting from the ground up, as a good citizen should.” Then the figures of the two men talking reappear. The street is now debouching into a traffic circle and public park. Atkins and Paul halt as having come to their parting-place.

Atkins speaks.

“That’s a great story you’ve given me. You won’t mind my writing it up for the ’Despatch’?”

Zelinka protests.

“But you’re not a journalist!”

“I’m going to be. Just as you are going to be an industrial prince. I’m starting from the ground up, as a good citizen should.”

Atkins disentangles himself from Paul after a little dispute, in which Atkins insists on doing what he wants to do and departs. Zelinka makes a gesture of vexation and watches Atkins’ receding back. Then he walks on slowly in his own direction. His father appears like a great shadow behind him, becomes more real and more nearly his own size, seems to talk to him and lays a hand upon his shoulder.

“Forget you are a Prince. Let everyone forget it.

“Forget the Old World. Begin—a man—in the New.”

Zelinka regrets his frankness with Atkins more and more. The figure of the father vanishes, but the son is so preoccupied with his thoughts that he does not note a pretty young woman in a small runabout car, who is going very slowly beside him and trying to attract his attention.

Then at a particularly vigorous blast of her claxon he looks up, discovers and salutes her.

She draws her car up by the sidewalk and they talk, he with a foot on the running-board. They are evidently close and warm friends, but so far, as their manner shows, there has been no love-making between them.

“Don’t be late for my father’s lecture.”

He looks at a watch. He will be there. They talk, and she discovers he is preoccupied and questions him. He says it is nothing, nothing at all, but she presses him.

“I’ve been talking like a fool about my father to a man I didn’t know was a journalist. He’s trotted off to write an interview, and unless I go after him and kill him he’ll do it. I suppose he’ll call me Prince Zelinka or Grand Duke Zelinka—and after that what chance have I in Steelville of being Paul Zelinka, the citizen of the world?”

She tries to reassure him, but he is in a mood of foreboding.

“Talking with that journalist has brought my father back to me. Again and again he said to me: ’You belong to the New World, the world of human unity. It is your birthright. The Old World is division and war, rank without effort, and servitude without hope, tradition and decay. From that, this land is escape.’”

She watches his face. The words float over them:

“I hate these titles that cling to me.”

The Clavopolis Palace garden scene reappears, but taken through a distorting lens and superimposed upon Paul Zelinka and Margaret talking together. The court officials are still there, but grotesquely changed, and the old King is raging. He points to Paul as if commanding his recall. Atkins appears like an impish gnome with a notebook in hand. The officials seize upon Paul and attempt to put him in uniform. The words, PRINCE, DUKE, NOBLESSE OBLIGE, HIGH POSITION, float through the air. A vast crowd of American society people seethes about him, hounded on by Atkins. Paul struggles against these things, all distorted by the lens. He and Margaret become involved in this thought vision. He takes hold of Margaret, and they struggle and swim against all these formal and traditional things towards a large clear place. There appears a pioneers’ covered waggon into which they clamber and drive off. It recedes across a vast plain. It is pursued by a threatening cloud that takes the form of an armed figure. Against the horizon, bright, remote, and clear, rise the buildings and pinnacles of a splendid dream city towards which the waggon, now very remote, pursues its way. But the dark cloud spreads over the whole sky and swallows up the prospect. On the screen against the darkness appears, I fear the Old World, and then the two grave figures of Margaret and Paul, talking over the side of the car, are restored.

She has an idea. She puts out a hand towards him as if to hold his attention.

“But are you sure that America IS the New World? Did your father really mean that? MY father says that the New World is everywhere and the Old World everywhere. The New World stirs now almost as much in India or Angora or Berlin or Moscow as here. So my father says.”

Yes, that is an idea worth considering. Then he laughs.

“Well, Atkins will pull all the Old World down on me if anyone prints his interview.”

“Perhaps they won’t print his interview!”

She smiles. There is a little pause between them. Both are shy. She glances at her wrist-watch and starts her engine.

“Don’t be late for the lecture.”

Again there is the momentary hesitation so characteristic of incipient lovers. Then he stands back and watches her depart.

The film now plunges into the midst of Dr. Harting’s Steelville lecture upon The Causes of War.

Dr. Harting is an old distinguished-looking American, lean and tall, after the type of the late President Eliot of Harvard. He uses glasses to read his notes, and holds them in his hand while he speaks, often tapping the papers. He stands upon a platform at a reading-desk. Behind him are diagrams, indistinctly seen at first, and a chairman sits beside him. The picture is photographed with the camera turned somewhat upward in such a way as to make Dr. Harting slenderly dominant, like the prow of a ship.

A glimpse is given of Zelinka and Margaret sitting together in the front row of the audience, and then one sees a few other figures in the audience. Man the Destroyer is present, hostile and critical, and several commonplace and excitable types.

The lecturer says:

“Do not imagine you can secure the Peace of the World by good resolutions. So long as you have national flags, national competition, national rivalry, you will have war.”

Man the Destroyer in the audience shouts, “Traitor,” and an old gentleman sitting near him says, “My country, right or wrong!” and looks round excitedly for approval.

A middle-aged man rises, points to the lecturer and says:

“You go too fast and too far.”

The picture centres back on the lecturer.

For a moment he has to content himself with gestures. Then he says:

“Well, here is a case in point. The calcomite dispute.”

He takes up a pointer and the map of perverted geography which has already figured in the opening scenes becomes clear and distinct. The lecturer’s pointer passes across it.

“There, locked up in Agravia, are the richest calcomite deposits in the world.”

He becomes quietly argumentative.

“Since the new processes came in, calcomite has become vitally necessary for all the metallurgical industries in the world—except for the British, who have their own supplies in South Africa and Malaya.”

The audience needs a little time to take that in. Faces show expressions of suspended interest. The lecturer pauses before his next point.

“Has Agravia, with British collusion, the right to play the part of Dog in the Manger to that calcomite?”

The audience is divided about its answer.

Man the Destroyer leaps to his feet. “If we need that calcomite vitally, we have a right to take it.”

Others approve him.

An argumentative little man in spectacles, addressing all and sundry, says:

“We can’t have our national industries strangled by a geological accident.”

The dispute grows hot. Here the musical accompaniment may be supplemented by gramophone voices. Such phrases as: “Rights of nationalities,” “Plain justice,” “Common sense,” “Sacred Egotism of a Great People” and so on, float indistinctly into the music.

The lecturer waits for a moment of comparative quiet.

“How in the world at present is a question like that to be settled?”

Man the Destroyer stands up again, and with a gesture to the people about him cries: “Let the British release that calcomite!”

Applause, and voices shout approval in the music. A distressed innocent little man is seen trying to attract the lecturer’s attention:

“But the Kellogg Pact has outlawed war.”

The lecturer tries to hear him, signals to him to say it again, and then realizing what he is saying, answers with a lean finger held out.

“But the Kellogg Pact doesn’t help us a bit to solve the calcomite difficulty! Or any other difficulty.”

A neighbour of the distressed innocent little man pokes him and says to him:

“The Kellogg Pact hasn’t stopped the building of a single submarine. If it meant business the world would disarm.”

The Evil Man bawls:

“Let the Europeans stand out of our light or take the consequences.”

Evidently he carries with him the warm response of a number of excitable people sitting about him. He gives a form to their instinctive feelings. “This is sense,” their faces say. They shout down the innocent little man.

The long finger of the lecturer goes out towards Man the Destroyer: “And how about the National rights of Agravia?”

Man the Destroyer answers: “Our National rights come first!”

Manifestly many of the audience are with him. The American flag streams phantasmally across the picture. Then across it, following its waving lines, streams the suggestion of a battle fleet. This fades almost to invisibility, and the lecturer comes to his point.

“There is one thing other than War that can decide the question.”

This is held for a moment before the one thing is defined. “A Cosmopolitan control and rationing of calcomite.”

And then—

“And all natural resources.”

Men turn to each other in the audience as if to ask, Is this possible? And then Man the Destroyer, to check the wavering, shouts: “That is a dream!”

Then he spreads his arms out, with his fingers curved like claws. He is enlarged until he fills the screen. He is dark, evil and loud.

“This is to sacrifice your independence!”

The faces of Margaret and Paul are seen attentive to all that is happening, and then the faces and gestures of individuals and groups in the hall. The hall is allowed to appear very large, it suggests now the world audience to modern thought, and little groups of nationals appear—Germans inclined to agree with the lecturer, Italians with little flags, a group of English and Irish, a storm of types. The following phrases are flung across the disputing confusion. They are flung across the picture and also they are shouted by the gramophone:

“Would Britain stand for anything of the sort?”

“What would Agravia say?”

“Every nation is absolute master of its own soil.”

“This would be an entanglement for us.”

“George Washington said we were to stay apart—for ever.”

“But we need calcomite!”

“We need calcomite!”

“We are strangled for want of calcomite!”

“We shall have three million unemployed.”

“War.”

The lecturer stands out, high and logical, above the confusion. Presently he begins again.