|

Project Gutenberg

Australia a treasure-trove of literature treasure found hidden with no evidence of ownership |

BROWSE the site for other works by this author (and our other authors) or SEARCH the entire site with Google Site Search |

Title: Abeniki Caldwell Author: Carolyn Wells * A Project Gutenberg of Australia eBook * eBook No.: 1601251h.html Language: English Date first posted: December 2016 Most recent update: December 2016 This eBook was produced by: Walter Moore Project Gutenberg of Australia eBooks are created from printed editions which are in the public domain in Australia, unless a copyright notice is included. We do NOT keep any eBooks in compliance with a particular paper edition. Copyright laws are changing all over the world. Be sure to check the copyright laws for your country before downloading or redistributing this file. This eBook is made available at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg Australia Licence which may be viewed online.

GO TO Project Gutenberg Australia HOME PAGE

Chapter I. The Napoleon Feather

Chapter II. The Poisoned Handkerchief

Chapter III. D’Orsay’s Left Foot

Chapter IV. The Pot Of Painted Butter

Chapter V. An Easter Greeting

Chapter VI. The Brass Andirons

Chapter VII. The Loyalty Of Lorraine

Chapter VIII. The Six-Sided Square

Chapter IX. The Counterfeit Ticket

Chapter X. The Isabel Scarf

Chapter XI. The Ides Of March

Chapter XII. The Red Rosette

Chapter XIII. The Confession Of Callimachus

Chapter XIV. The Tricolor Of Lorraine

Chapter XV. The Somnambulist Of The Monastery

Woe betide us,—all is lost!”

These words, uttered in an ominous, despairing shriek, pierced on mine ear with prophetic force, and I knew my glorious hopes were doomed to disappointment.

“Ha!” I thought silently to myself; “who hath spoken? Who, with a bold disregard of time and place, hath dared thus to utter his fateful conviction?” I glanced cautiously about me.

The scene was a dazzling one, and right merry withal. The spacious ball-room, hung with posy garlands and twinkling with a myriad wax-lights, formed a fitting field for many a gay bud and blade who danced away the hours all unwitting of their approaching doom. Ah, thus had there been a sound of revelry by night when the Assyrian came down like a wolf on the fold, and sic semper tyrannis.

I hesitated for the millionth part of a second, and then, for I was ever impetuous, I dashed across the room and seated myself in a red velvet armchair. Red velvet, did I say? Red! nay, by my troth, ‘twas blue,—blue as the violets nodding by the mere; blue as the noble blood that coursed through the royal veins of Francis, England’s greatest king.

It was foolhardy, that mad dash across the apartment; but as I had foreseen, the manoeuvre outwitted my enemies, and, all aglow with satisfaction, I addressed myself to Lady Alys Allardyce, who gazed at me over her peacock-feather fan with eyes of not unfathomable meaning.

“Hist!” said she, lifting a warning forefinger, “listen thou, but speak no word.”

“Aye, madam,” I murmured in return, for I was ever obedient; “I am dumb before thee; thine shall be the discourse, thine the explanation. Mine is it silently and humbly to obey thy orders, even though they lead through Danger to Death. At thy bidding I embrace the direst Danger; at thy behest I rush eagerly to darkest Death. “Queen of my heart, accept the proffered aid of thine humblest servant and give me the straight tip.”

“’Tis well said,” quoth Lady Alys Allardyce; and in silence I proceeded to adjust my purple velvet cloak, which hung in graceful folds over my white satin doublet slashed with cloth-of-gold.

“But,” said my ill-fated companion, and her clarion-like voice sank to a faint falsetto, “the time is ripe; yet ’tis an evil hour when I, a daughter of the House of Harlech, shall betray such gruesome secrets to an alien ear.”

“And shall the vaulted chamber remain forever locked?” I cried.

“Alas, no,” she answered, “the Curse of the Clurichaune must fall—must fall!”

She spoke the last words with a Cassandra-like look that sent shivers to my spine, but I replied,—

“The Curse of the Clurichaune will fall, but only after the Cyprian scorpion shall have strewn the desert with the bones of his traitorous-hearted victims.”

This moved her, and I looked up to see the Lady Alys smiling at me from the other side of the room.

Shivering with cold, I drew my plaid more closely about me and strode onward across the Scottish moor. The night was dark, and the storm came in fitful gusts, bending the old sycamores until they snapped from their stems and lay prone in the dense shadows of the forest.

My heart was filled with a black bitterness of woe, and ever in my ear a demon seemed relentlessly to hiss, “Revenge! Revenge!”

I had traversed perhaps a dozen leagues of misty moorland when I heard a sound behind me.

Grasping my rapier, I looked back, but I saw nothing, so dark was the night.

’Twas only by listening intently I heard the sound of wheels and the clatter of horses’ hoofs on the asphalt.

“Who comes?” I cried, as I valiantly drew sword, and prepared to defend my life against hostile attack.

A piercing shriek was the only answer.

But such a shriek! It made my very heart stand still with mingled joy and grief.

For it was a noble, educated, aristocratic shriek; a polished, cultured shriek; a gentle, refined, musical, and altogether-to-be-admired shriek. Such a shriek, in fact, as could proceed only from the ruby lips and pearly teeth of a fair damsel in distress. Surely some beauteous maid of noble birth had exercised her patrician lungs in bewailing some troubles of her own.

And, again, her mishap or misfortune, if mishap or misfortune it were, was dire, sudden, and unexpected.

For the shriek, though of enchanting sweetness of tone, was pitched in that high key, and phrased in that staccato accent which always betokens fear, terror, or distress.

By a series of swift mental computations relating to the square of the sound plus the distance, I arrived at the conclusion that the beautiful unfortunate must be exactly two miles and a half away from me in a northeasterly direction.

“By the helmet of St. Swibert!” I exclaimed, “the prowess of this single arm shall serve to rescue suffering Beauty from aught that may assail,” and in tones of hope and reassurance I called to the unknown Fair One:—

“Fear not; a sword and lance are at thy service, O Damsel in distress! I will protect thee.”

I paused only to gird my gabardine more closely round me, and then set off hot-foot for the scene of carnage.

There are few more imposing bits of scenery in all France than the castle-yard at Coningsburgh, where, well defended by walls and ditches, rises the ancient edifice, which was, previous to the Conquest, a residence for the royal kings of England.

Eagerness and excitement acted as wings to my feet, and I fairly flew across the moor, and arrived on the spot just in time to see a coach and four come tearing madly round a turn in the road.

The horses galloped at such a pace that the coach rocked from side to side; the postillions, pale with fright, shook in their saddles, while the outriders clapped spurs to their horses and disappeared round the edge of the cliff.

The coach was a brave one, gilded and painted in the style of Louis XIV., and the servants’ liveries betokened a house of rank.

But ere I could more than glance at the fair, frightened face in the coach window, I perceived the cause of the hubbub to be a dozen or more attacking brigands, who on coal-black stallions pursued the fleeing coach.

“Halt!” I cried in stentorian tones, and held up my right hand with a menacing gesture.

The chief of the brigands advanced with a bold front, but I thought I detected a quiver of his left eyelash.

“Varlet! who art thou?” he cried, and lunged at me with his naked sword.

“I am Claude Kildare,” I replied, “and right dearly shalt thou pay for daring to attack a Kildare of Kildare.”

So saying, I dashed at him, and ere he might so much as wink an eye, I sent my sword through his heart, and drew back the flashing weapon dripping with the fiend’s gore.

A yell of rage broke from his companions.

Roused to fury by the death of their chief, they attacked me with cries of vengeance and I had great to-do to parry all their thrusts at once.

But by a clever bit of sword-play I killed two of the brutes and struck the swords from the hands of three others.

Then with my left hand I fired my revolver six times in quick succession. This did for six more, after which I had only four to contend with.

Infuriated to the verge of frenzy, these demons in human shape flew at me.

One clutched my throat, but with a swift, clean cut I severed his arm, and then turned sharply on the others who were attacking me from behind.

“Come on!” I cried, for my spirit was roused, and another glimpse of the fair face at the coach window urged me on to grand-stand play.

They came on, since I insisted, and one behind another approached me with fell intent.

“Dogs!” I cried, and with a blood-curdling yell of triumph, I ran my trusty sword straight through the five,—aye, spitted the rogues as a cook runs a skewer through reed-birds.

They fell, weltering in their own gore, and then, resuming my courtly air, I turned to the damsel in the coach. I bowed before her, sweeping the ground with my plumed chapeau, and said simply: “Lady of the Starry Hair, Glory of Three Realms, if that my trifling aid hath shown thee aught of my devotion, grant me but one glance of thy Heaven-beaming eye, that the memory may be to my future life a fountain of exhaustless joy.”

“Nay, bold cavalier,” said the lady, “though in no wise do I underrate the assistance thy good sword hath rendered me, yet I am the Princess Berenice of Bois-Bracy, and the daughters of my house may not so much as glance upon one of lower birth and less boodle.”

Chagrined and humiliated beyond words, I exclaimed: “Ha! how report hath lied! Full oft have I heard of the beauty of the Princesses of Bois-Bracy, but even through thy thick veil of black bombazine can I see thy hard-featured and ill-favored countenance.”

The ruse was successful. With a slow sudden gesture, the Lady Berenice flung aside the bamboozling bombazine and disclosed such marvellous beauty as was never seen, save and except in advertisements of certain soaps and dentifrices.

Oh, that face! that face that gazed out from the coach window as from a frame of gold! Heaven forfend that I should attempt to describe its glorious beauty! The pen of a Watteau were all too poor to give even a faint inkling of those angelic features.

The pure Greek profile outlined a classic brow and a nose which Mr. Micawber might have waited for; while the fair cheeks were like new pink satin pincushions.

Masses of golden hair rose from the ivory temples like clouds of incense, and the lips of carven coral might well have served as a model for Cupid’s bow.

All this I saw ere the downcast eyes were raised, but when the dark-fringed eyelids lifted and the Orient orbs of Lady Berenice thrilled to mine own, I knew that my life had at last begun. For love is life, and they be not alive who be not alove.

Still ’neath the spell of that glistening glance, I opened the coach door and my lady stepped forth.

Till then I had seen but her face; now I perceived that her form was equally fair and noble. Tall as an Amazonian goddess, yet not too tall to be called petite, her straight, arrow-like figure was full of graceful curves.

Her robe was of orange wool, with a kirtle of pale crimson silk looped at the side. Her outer garment, or toga, was of maroon mohair with gilt fringe. Bracelets of beaten gold adorned her beautiful arms, which were bare to the shoulder, and on her feet were sandal-wood sandals.

“Most Radiant Blossom from the Garden of Paradise,” I began, for I was ever plain and simple of speech, “behold before thee thy humble grovelling slave, whose only greatness is his unbounded devotion to thee and to thy service. Goddess, accept my homage; grant only that I may bow in the dust before thee, and when thou liftest thy dainty foot, oh, graciously permit that I may get it in the neck.”

The Lady Berenice was touched, but bravely concealing her agitation, she whispered,—

“An thou lovest me, drive me post-haste to the Inn of the Royal Rogue, over Borneilshire way.”

“Pride of the Universe, I live but to obey,” quoth I, as I handed Milady into her coach, touching her fingers awesomely, for who was I that this great honor should come to me?

But as the Lady Berenice glided into her cushioned nest, something fell to the ground from the folds of her garments.

Only two or three tiny, almost imperceptible fragments, yet as I saw them, my heart stood still in my breast, and then beat fiercely with a mad passion which I could not quell.

Anger, wrath, indignation, resentment, bitterness, animosity, exasperation, rage, fury, pique, umbrage, dudgeon, acerbity, virulence, and spleen strove for mastery in my infuriated brain.

Not for me this fair Marvel of Maidenliness, not for me this Miracle of Magnificence; and with a horrisonous groan, wrung from the very subway of my aching, breaking heart, I forcefully brought down my heavy heel and ground deep in the dust those three grains of rice.

High toward the blue-vaulted heavens waved the silvery branches of the cypress-trees. Drifting blossoms fell from the brambles, and, blown by the west wind, scampered across the heath toward the setting sun.

The frowning Palisades, crowned with their Autumn foliage as with a wreath, looked down upon the peaceful Hudson with an air of mingled protection and superiority.

Far to the south, the magnolia groves nestled among the hills of the Carolinas, and their waxen blossoms flashed in the pale moonlight with an eerie beauty all their own.

The reapers paused, and as the morning broke in unclouded splendor o’er the peaks of Darien, the mist of a dismal February evening was spreading its humid veil over the line of low sandhills between Lochaber and Liddesdale.

The verdure fairly rioted in the wild exuberance of early Springtime, and the freshly washed Day seemed to break forth in a glad, sweet smile that had been ripening for years. But the gayety of Nature struck no answering chord in the sooty heart of Claude Kildare.

Slamming the door of Lady Berenice’s coach until it seemed as if she must needs lose her balance, her angry cavalier sprang with one bound to the coachman’s box, and gathering up the ribbons started the six startled steeds off at a mad gallop.

By the bones of St. Dunstan, what a ride it was! The horses scarce touched ground at all between their pounding jumps, and the foam fairly flew from their fangs.

On, on, across the miry dunes,—on, Claude Kildare! spur thy horses through brake and brush, lash them o’er ditch and gorge; bravely balance the reeling vehicle, now on one wheel, now on another,—and, by the Pibroch of St. Winibald, thou shalt outstrip the pursuing hordes and win fair fame, forsooth, by thy high venture.

Within the coach the Lady Berenice lolled indolently on her satin cushions.

“Ha!” she said to herself, “methinks peril attendeth.”

With a faint interest manifest in their dark depths, the lovely eyes turned a glance of mild inquiry upon her new-found charioteer.

“Now, marry beshrew me!” cried the daughter of a hundred earls, “but the knight hath a marvellous skill. An a man can drive eight prancing steeds while he beareth his shield on his left arm, and holdeth a cocked revolver in his right, I need fear me no fears.”

And so, content of her safety, the beautiful Lady Berenice sank into a gentle slumber, little dreaming of the dark and deadly plots that seethed in the throbbing brain of Claude Kildare.

Thus they rode on, and as the sun’s dazzling disc dropped darkling into the horizon, they arrived at the postern gate of the Golden Grasshopper.

“Alight, O, Fair but False,” quoth Claude Kildare, throwing open the coach door; and with a firm, haughty step the Lady Berenice alit.

From the Inn, behold advancing, with a fat, unctuous waddle, Joseph McCann, this twelve years Keeper of the Golden Grasshopper.

His hostelry was marked by the rude simplicity of its period, and its façade of white marble rose unostentatiously toward the blue heavens to the height of twenty-two stories.

A simple flight of white marble steps, carpeted with plain red velvet, led to the main entrance.

Herr McCann, though now in his thirty-seventh year come Michaelmas, had a hasty and choleric temper and was greatly slow-witted withal.

His long yellow hair was parted amidships, and fell on either side his head down to his shoulders, while a steely glitter was in his either eye.

His dress was very sumptuous and magnificent. A scarlet tunic hung from his left shoulder, disclosing a green doublet edged with ermine.

“Odsbodikins, fair strangers,” he cried, “come in, and right welcome be. How are ye named?”

“I am Gaston K. Waldemar,” said Claude Kildare, “and this lady is my mother, Mrs. Waldemar.”

This statement was a lying falsehood, and Lady Berenice knew it, but awed by Kildare’s menacing glance, she said no word.

“Give this lady a suite of rooms,” continued Claude, “the finest your house affords, or, by the hammer of St. Dubric, I’ll break every skull of your head. Where is the lift?”

“This way, my lord,” replied the Innkeeper, trembling like an aspic leaf, and he preceded his guests along the electric-lighted palm-corridor.

Claude Kildare strode in the direction indicated and Lady Berenice glode silently by his side. He clasped her fair hand at parting.

“I will await thee,” he murmured, and his voice was as the cooing ring-dove’s, “at nine o’ the clock, by the moon-dial in the rose-garden.”

The Lady Berenice uttered no word, but she flashed on Kildare an eloquent glance which seemed to say, “Naught shall keep me from the tryst; I will be there unless perchance it should rain.”

Ah, little thought the fair Lady Berenice that already the knell of her happiness had tolled, already the memory of her future was menaced by poisoned shafts fired from the guns of envy, hatred, and malice.

Claude Kildare raised his head, and with a smile that dispelled the lowering clouds from his brow said gently: “Gramercy, good yeoman, and now hast ale in thy vaults?”

“Aye, my lord,” quoth the Innkeeper, “prime ale and wine of the best, long kept in store for such as thou. Ho, Varlets, a stoup of Malvoisie!”

His command was obeyed by a passing lackey, and our hero entered the Gothic grill-room and flung himself at table.

The crowd of merry roysterers carousing there paid no heed to his entrance, but continued boisterously to brawl a roundelay.

“Here’s to Hilarity,

Jolly good fellows we.

Fill up your stein with Rhenish wine

And drink with me.

“Drink to the death of care,

Drudgery, and despair;

Drink to a life with Laughter rife

And free as air.

“Here in content we sit,

Bothering not a bit,

Though in the world’s mendacious mart

Men fret and smart;

“Though in a morbid mood,

Greedy for solitude,

Anchorite grim in cloister dim

May sit and brood.

“We have the better lot,

Here from all fetters free;

Happy with Pipe and Pot,

Pledged to Hilarity.

Ha,ha,ha!”

But of a sudden their jollity was interrupted by the entrance of a sinister-looking, ill-favored man.

O’er his beetling brows was pulled low a black fur cap. Around him was wrapped a long, black cloak, from the folds of which gleamed a hidden rapier.

With angry frown and surly scowl he said,—

“A truce to this fooling! Cease these loudmouthed japes and jibes! Hath not the cause been neglected these many moons? Are not our spears rusty in their scabbards? Do not our truncheons hang idle on the walls? Go to! These things must not be! Boleslaus, dog of a slave, get a move on thee and arm for the conflict!”

“By the Great Horn Spoon,” quoth he addressed as Boleslaus, “that will I not do. Only yestreen Bertran of the Red Nose played on me a most scurvy trick. What did he? This did he! When that I would—”

“Hah, sirrah,” interrupted a burly youth, springing to his feet, “darest thou denounce me? Have a care!”

“Spine-of a Lobster!” roared the latest-entered one, “cease this buffoonery! This hall hath more the air of the den of a brawling brotherhood than the abode of peaceful gentlemen. Make short shift of thy quarrel, that we may dine orderly. But, soft,—an alien is here! Thy name, sir, and thy business?”

As he spoke, the fierce-looking intruder advanced upon Claude Kildare, and brandished his rapier in our hero’s face.

“Swashbuckle me no swashbucklers, thou miserable caitiff!” cried Kildare. “Know that I am a Kildare of Kildare, and he who tastes but once of my cutlass will never use any other.”

“Kildare!” muttered the aggressor, while his face went white and a sudden change o’erspread his features. “Kildare, sayest thou? Ah, my dear old Aunt Rhoda, my-mother’s second cousin twice removed, married a man whose first wife was a Kildare, ah, me! ah, me!” Claude was touched, but as he had his fingers crossed he wasn’t it, so he proceeded,—

“Foul craven, ‘tis but too true! And for that dastardly crime thou shouldst have been en-dungeoned for life.”

“Ha-a-ah, say not so,” muttered the other, in a blithering voice, for indeed right frighted was he, and of great dolor.

“Hist!” roared Claude, “utter no word, but utter silence! I command thee! What is thy name?”

“How may I tell thee if I may not speak?” sulkily muttered the other.

“Reptile! darest thou thus bespeak me? Silence! I say! and tell me thy unworthy name!”

“Don Giovanni Ziffkoffsky,” growled the victim, with a rough red glare at his tormentor.

“And thy business here?”

Kildare’s tone was forcefully mild, but his eyes shot venonomous darts at the man he questioned.

It must be conceded that other things being equal, and granting the investiture of all insensate communication, that a psychic moment may or may not, in accordance with what under no circumstances could be termed irrelevancy, become warily regarded as a coherent symbol by one obviously of a trenchant humor. But, however, in proof of a smouldering discretion, no feature is entitled to less exorbitant honor than the unquenchable demand of endurance.

Though, of course, other things being equal, and granting the investiture of all insensate communication, no feature is entitled, in accordance Kildare's tone was forcefully mild, but his eyes shot venonomous darts at the man he questioned with what under no circumstances could be termed irrelevancy, to become warily regarded as a coherent symbol. And doubtless, in proof of a smouldering discretion, and in accordance with one obviously of a trenchant humor, it may or may not be warily regarded.

Though it cannot be denied that the true relevancy of thought to psychic action is largely dependent on the ever-increasing forces of disregarded symbolisms. And this, again, proves the pantheistic power of doubt, considered for the moment and for the subtle purposes of our argument, as faith. For, granting that two and two are six, the corollary reasoning must be that no premise is or may be capable of such conclusion as will render it sublunary to its agreed parallel.

But this view is ultra, and should be adopted with caution.

We are therefore forced to the conclusion that pure altruism is impossible in connection with neo-psychology.

In view of this and in consequence of which, Don Giovanni Ziffkoffsky answered and replied:

“Claude Kildare of Kildare of Kildare, I am a scion of proud and haughty lineage. I am haughty with the haught of a long line of noble nabobs, and, for myself, I scorn thee! Ay, scorn thee with all the objurgatory contumely of a proud soul. But—there are others. No longer am I a Solitary. No longer am I the Bachelor, the Misogynist, the Celebrated Celibate. To-day, ah, but only to-day, led I to the altar a blushing bride, a lily-like lady, who vowed unfaltering fealty—”

With one stride Claude Kildare crossed the great hall and clutching Don Giovanni by the throat shook him as a housemaid shaketh her dusting-clout.

“ ’Sdeath!” cried Claude Kildare, and his eyes blazed like headlights, while his voice was as a train which roareth in the tunnel.

Don Giovanni shook with alarm, but said no word for cause of Claude’s throttling thumbs.

“Ha, Poltroon, thou milksop, thou jelly! dost thou quiver with fear? Then will I scare thee stiff!”

Having made good his threat, Claude continued,—

“Scum o’ the earth, Dreg o’ the dust! where is she? What hast done with the fair maiden, the beauteous bride of an hour?” Don Giovanni hesitated; Claude Kildare waited,—waited and yet waited. The room was as still as silence.

Kildare held his breath, and waited.

The old Union clock struck. After an hour it struck again.

Then Claude Kildare, being of impatient humor, kicked Don Giovanni and hissed, “Answer, Varlet! ’Tis up to thee.”

Don Giovanni pouted and said, “Cease thou to badger me. I know not where she may be. Brigands attackted our wedding coach, and I was obliged to flee for my life.”

“Now, by St. Anthony!” cried Claude Kildare, “ ’tis as I guessed. And her name, proud bridegroom?”

“Lady Berenice—” began the Don, but Kildare raised a threatening hand.

“Enough!” he said, and his voice was quiet,—ay, even as a mill-pond is also quiet just before its dam breaks,—“enough, I perceive thy finish. But I am magnanimous of soul. ’Tis mine to kill thee,—and far be it from me to deny my joy therein,—but ’tis thine to choose the manner of thy taking-off.”

“Nay, not so,” quoth the Don, with politeness of speech; “duels of all sorts are to me but as child’s play. Do thou choose.”

“I command,” said Kildare, drawing himself up to his full height of seven feet six; “obey instantly and select thy choice of place and weapons, or, by the beard of St. Dunstan, I will bury thee alive!”

“Then, my lord,” said Giovanni, with a mocking gleam in his eye (he had but one), “then I choose a duel on a tight-rope that shall be stretched across and above the Black Devil Falls.”

Claude Kildare stood impassive, as one awaiting a matter of no great concern. Then hearing the Don’s choice, he carelessly flicked a stray caterpillar from his jerkin-sleeve, and said,—

“Aye, it shall be so. And, mark thee, it shall be to-night at midnight, our path unlighted, beneath a black and moonless heaven.”

Sith it hath befallen that to me and none other is entrusted the record of certain momentous deeds, since Fate hath writ that the chronicling thereof shall be vested but in my unworthy self, then, as Thackeray hath it, the time is ripe, and with an eye single to one grim but grave intent will I plunge bravely and valiantly into the recital thereof, with no merry wanderings into flowery by-paths nor dallyings in pleasant gardens.

Mine is it not to detail the gory adventures of the Crusaders in their search for the Golden Fleece. Ever must I be silent regarding the weary, vain endeavors of King John to gain the governorship of Paris. And though my pen struggleth in my fingers to write of the daring deeds of Prince Griffon in his royal galleys, yet I must needs quell these leaping desires, and egg on my fitful Muse to the tale that doth more intimately concern us. As I emerged, then, from the smoke-reeking atmosphere of the grill-room of the Golden Grasshopper, I found myself beneath the starlit vault of a black and murky sky. The rain fell in torrents, but all unheeding the dampness I stalked on, with monstrous thoughts crowding my ponderous brain.

“If it be,” I reasoned all subtly to myself, “then by the rood, ‘tis not so worse. And yet were it not so,—ha! the thought maddeneth me! That were a lucky chance, and by the belt of St. Christopher ’t would save the day and evermore the black and guilty truth should shrivel and burn secretly in the depths of my oppressed soul. Ha! this martyr-like vengeance shall yet be mine; and from the accursed cell, shrouded in deep and inscrutable mystery, the ominous arrogance of a noble slave shall—”

I paused, perforce, for as my martial footsteps fell resounding on the soft green turf, I checked my right foot raised rigid in the air, lest it trample something that lay before me.

With mingled feelings of uncertainty and indecision I gazed down at the tiny face whose wide-open eyes stared up into mine own.

“Give thee good-day, mannikin,” said I, for I was ever merry and jocose of speech, “and verily thou hast but narrowly escaped my grinding heel on that fair face of thine. Another halfpace, forsooth, and I had spoiled for aye thy rosy cheeks and the grinning red mouth of thee. Art glad, small one, art glad that thy beauty wast spared the havoc of my fitful footfall?”

Still clacking thus, in flippant whimsey, I stooped and raised the inanimate little form and dandled it high in the air.

“Gadzooks!” quoth I, “but thou ’rt a gay one! Thy striped doublet and lace collarkin proclaim thee of the royal household. Wouldst thou couldst speak, and with thine own dumb lips inform me who leftest thee thus by night in the forest path.”

I shook the Bauble until all its bells tinkled, but its lips remained silent in a painted waxen grin.

“Tolderolloll and hey, troly-loly!” sang out a blithesome voice and gay, while with two bounding springs a motley figure dashed into view.

“Who art thou, man, and how yclept?” quoth I, looking with mirthter on his zany costume and his cap and bells.

“Heyday, I be Jack Pudding, the court-fool, and I pray you, fair sir, of your plenteous goodness, return back unto me my Bauble, my pretty popsey-puppet.”

“Is’t thine?” cried I. “Take it then, Scaramouch, and bless the shining Fate that betimes averted from thy treasure the iron heel of Claude Kildare.”

“Aye, aye, sweet chuck, ever heretofore shall Jack Pudding be thy sworn friend and humble minion. And may’st thou never sit down to flagon or pasty where I be not a welcome guest.”

“Tis well, ’tis well,” quoth I, awearied by his chatter. “And now, an thou lovest me, make thou thyself scarce, for I have weighty matters on my mind and I crave but a lonely solitude.”

“Now may the Devil brand me for a feather-pated fool!” exclaimed my companion; “what hath so beaddled my wits that I have erstwhile forgotten the message entrusted me for thee? Heigh-ho! a merry heart maketh an empty brain, and much laughter maketh the speech of little worth.”

“How now, Varlet,” I cried in rage, “hast a message for me yet untold? Ha! what fearful penance shalt suffice to avenge thy black misdeed? The taking of thy worthless life were all too small. But tell it me, tell me thy tale with all haste, and scarce shall the words have left thy lips ere thou shalt find thyself carrion for the roaring lion and the ranging bear. ’Sdeath! foul knave, shoot off thy miserable mouth!”

“Tira-lira, my most amiable friend, twiddle thy twaddle to fainter-hearted ears than mine. I fear not thy threats and would as lief trip away and leave thee yelping here. But hey-ding-a-day, it pleaseth my good-humor to humor thee, so will I tell thee the message. And ’tis but short, three brief words comprehendeth it: thus,—‘I await thee.’ Such, my lord, is the speech I was bidden to retail to thee.”

At the Jester’s words, my mind, ever fleet of flight, flew back to Don Giovanni Ziffkoffsky and his challenge.

“Tell the Sneaking Hound,” I exclaimed angrily, “that the message is received and that the awaiting may continue until midnight, when on the stroke o’ the hour I will face my unworthy foe.”

The court-fool bowed low.

“Now bless my bells,” he, cried, “an that be not a pretty message to send to a fair lady. But I will repeat it verbatim et infinitum to the beauteous Berenice, Queen of Love, Laughter and Song!”

“Berenice!” I cried, clutching at the fool’s striped doublet. But he danced off, leaving a yard of tinsel fringe in my hand, and ere I could speak again his voice sounded from full two blocks away.

I staggered and reeled. The sun turned black before my staring eyes, and with a piercing groan of grief, dolor, anguish, and despair, I sat me down upon a fallen yew free and buried my face in my feet.

Berenice! My love, my star! Princess of the world, enshrined forever in my faithful loyal heart! Heaven help me, I had forgotten all about her. Ah, that sweet message, “I await thee.”

What fonder words could an ardent lover hope for? What sweeter message could come to a devoted, adoring swain?

She awaited me, did she? the dear girl. Well, she should await no longer. Love should lend mercury-wings to my Cuban heels; Impatience should urge on my flying footsteps, and soon, ah soon, I should be with my Beloved, my bonny Berenice.

Giving way to my mad haste, I paused but to read the evening paper and smoke one or two cigars, then with heart aglow I sallied forth to keep my tryst.

As I neared the weeping-willow tree, ’neath which I had promised a rendezvous with Berenice, my heart ceased to be couchant and became rampant.

With mad haste I onward sped, and just as the cuckoo in the beech tree chirped forth his nine raucous notes, I clasped my Beloved gently but firmly to my armored breast.

As we stood there, alone in our new-found happiness, the world out-blotted, the universe forgot,—as I felt, e’en through my steel corselet and my coat of mail, the thrilling throbbing of my darling’s heart, all superfluous complications of thought and reason seemed to be swept away, and, soul to soul, we knew only the simple, elemental truth, “I love you.” And so in the plain, inornate speech for which I was justly famed I murmured:

“From the viewpoint of those controversialists, who it is thought by certain of mankind in their crass ignorance are quite reliable on matters of Love and Loving, but whom we constantly find making gratuitous allusions of an uncomplimentary nature to Love-at-first-sight, which, more than all others, deserves our leniency, and in most cases is equally as enduring as Love gradually acquired and slowly accelerated, though it be commonly signalized by the infallible earmarks of the clandestine interview and the tryst sub rosa, our love is even yet already doomed, damned, and condemned.”

“Noble Knight,” said the fair Berenice, wiping a pearly tear-drop from her blooming cheek, “thou say’st well,—but pause ere thou declarest thy love, for it is not meet that I shouldst list to thy tender of thy tender affection. Hearken to the sad secret of my heaving, grieving heart, then go thou into debate with thyself and judge if thou considerest a proposal apropos?”

Again the fierce fangs of doubt, jealousy, distrust, mistrust, and apprehension fastened themselves in the throat of my heart, and I cried out with a rising choler:

“Now the malediction of St. Winkelbrand rest on that infernal bridegroom of thine! Though thou wert his bride but for an hour, though thou sawedst him not even during that brief space by reason of his riding his snorting steed behind thy coach, yet even so, thou bearest his accursed name,—thou art a Ziffkoffsky of the Ziffkoffskieri.”

“Aye,” said Milady, “ ‘tis true, ‘tis too truly true.” And then, with a meek humility of demeanor, with an abashed, ashamed air, with downcast eyes and bated breath, Lady Berenice sank on bended knee, and dropping her sable veil over her fair, fat face, she murmured low, “Permit me to die!”

“Nay, by the Horn of the Galloping Gorgon, that fate, shall not yet be thine! But tell me, ere I divulge my secret thought, why didst thou wed with the dastardly Don?”

The Lady Berenice rose with a Delsartean grace, and throwing aside her voluminous veil, stood, a barefaced jade, with a mystic smile in her hoodoo eyes.

“An I tell thee why, wilt promise to ask no other question?”

“Aye,” quoth I, eagerly.

“Then,” said the lady, “know the truth. ’Twas but in payment of a bet”

Though consumed with a raging desirousness to know the details of so strange a wager, I curbed my curiosity and murmured idly, “I thought as much. I suspected it from the first. And now, Berenice of the Veiled Visage, wilt be mine own an that I end the life of thy churl of a husband?”

“Canst do it?” queried she, and her eyes gleamed with a dark light.

“Sapristi!” I exclaimed, “ i’ faith I can do it, and that with deftness and dexterity born of my love for thee. See?” and I bent my long, lithe, Damascus blade round until its point touched its hilt, aye, and passed beyond it in a second circle. “This sharp, shining sword shall pierce his shabby, scrubby, tuppenny-ha’penny heart, and the Valiant Victor shall return smiling, to receive his rich and rare reward.”

“So be it,” quoth the gentle Berenice, “plunge thou thy bloody blade again and again into his very vitals, and then return in triumph to thy waiting sweetheart, and learn thy fate.”

Her words fired me, but I returned, saying:

“Only one more request, fair flame of mine; give thou to me a token, that I may bind it upon my arm, and, made immortal by its blessed presence, may fare forth to the foe without fear and without approach.”

The Lady Berenice looked at the various parts of her feminine paraphernalia as who should say, “Which shall it be?”

She touched uncertainly her silken baldric, fingered her belaced crimson chasuble, and all but tore the morse from her cope.

“Nay,” said she, at the last, “not these, not these; to thee, my fair, my frumptious Knight, to thee, Pride of my Present, and Felicity of my Future, to thee do I grant a guerdon worthy of thy preposterous prowess. I bestow on thee,” and she suited the action to the word, “my hoop-skirt, and Honi soit qui mal y pense, which is to say, Honesty is the best policy.”

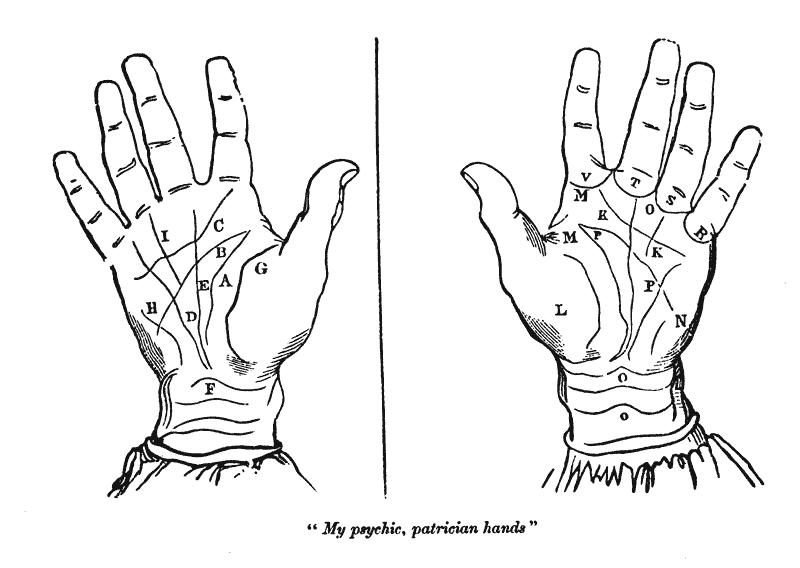

The Lady Berenice stood, like the Bartholdi Liberty, in her calm, uncrinolined grandeur, and outheld to me in her puny patrician hand the afore-mentioned token. A gracious light gleamed from her holy eyes, and half enamoured, half enawed of her splendid, exalted nobility, I bowed low at her feet, and kissed her velveteen skirt-binding.

“I accept the trust,” I breathed, though I could scarce speak for the awesome emotions which tumulted in my breast, “and I will return the token to thee, unscathed and unmarred by the fortunes of fierce war through which it must needs pass. Lady, I crave thy blessing.”

Binding the tender token about mine arm, I knelt gracefully before the fair maiden, and in the deepening dusk of that miasmic evening, she whispered paradoxical words of dire and blissful import above my bent and deferential head.

Now though a brave and lusty knight as might ever be, I am withal a monstrous plain-mannered man, and of vastly simple habit.

Modern inventions I hold to be the contrivances of the devil, and I care not a doit for the bumptious braggart who dubs them indispensable labor-savers. Witness this case:

Valiant of tread and light of heart, I strode, strong-legged and fleet, across the Scottish moor. The night was of a dark, dank duskiness that boded a fulfilment of the prophecy in my evening paper of “Cloudy: with showers.” This reassured my faith in those weather prognostications, which erstwhiles had been staggered by continuous unfulfilments.

For miles around no tree was in sight and I saw only the wide stretch of the heather, though its ruddy bloom was well-nigh covered by the fallen autumn leaves.

And dotted here and there, at convenient intervals, were the bluebells of Scotland.

Notwithstanding my rooted prejudice, I paused at one of them, and entering, said: “Four, O, Double-two, B, Grasshopper,” and after a preliminary and tumultuous delay of not over an hour I put the receiver to mine ear.

“Hola! Art thou the Lady Berenice of Bois-Bracy?”

Hola! Yea, and who art thou?”

“I am Claude Kildare.”

“Lord Bilmaire? Marry, thou’rt welcome! What wouldst with me?”

“Nay, thou hast the name wrong. I say ‘tis Claude Kildare!”

“Hard to bear? Ah, my lord, what troublest thee? I would I could comfort thee; wilt call to-night?”

“Now, beshrew thee for a fickle jade! I who speak to thee am,—Hola! Hola! Central, cut me not off, I beseech. Nay, I be not yet through! Another is even now on the wire. Is this the—nay! I be not Hakim the Swineherd! Thousand thunders of Olympus! Hola! Hola! Central, am I to have a clear wire, or Gadsbodikins, my blade shall run thee through ere break o’ day.—See then that thou dost, and now give me again Four,—Hola? Yea, ‘tis I, Lady Berenice, ‘tis Claude Kildare—Body o’ me! Canst thou not yet understand? Then list! A, B, C,—C—hast that?”

“Yea.”

“Hola! list yet again! A, B, C, D, E, F, G, H, I, J, K, L—L—art on?”

“Yea.”

“Now for’t! A—A, ’tis A! Hast it?”

“Yea! Marry beshrew me, art Claude Kildare?”

“Aye, Sweet One! Fairest Flower of a summer night! And lovest thou me?—What?—Louder! Hola! Hola! Central! Give me Four, O, Double-two, B, Grasshopper.”

“Subscriber busy—doth not reply. Subscriber busy—doth not reply.”

In deep disgust I hung the receiver on its peg, and with a swashing stride plunged out into the night.

Mounting again my noble steed, I clapped spurs to his sides, and rode far and fast to meet my dastard foe. As I rode, I heard the tinkle of silver bells, and a merry voice cried:

“Hey ding-a-ding! Tarry yet for me!”

I drew rein and in a trice Jack Pudding appeared, and with a bound sprang to my horse behind me.

“On, on,” he cried, “no time to lose. The Don hath already gone by at a tearing pace. I’ll to the fray with thee, for I dearly love a brave fight, and thou need’st a merry-maker to chirk up thy spirit. Heigh-ho!”

“Peace, Sirrah!” I cried, for I was ill-disposed to listen to the chatter of the feather-pated fool, having on my mind much momentous concern.

On we flew, my horse’s hoofs striking sparks from the wet leaves with which the highroad was strewn, on, and at bare five minutes before the midnight hour pealed from the belfry of St. Paul’s we reached the Boulevard des Males-herbes.

“Prithee, Jack,” I whispered, “hold thou the steed; methinks I’ve time to pause here at the Outside Inn, and snatch a beaker of sack.”

“Aye, do,” quoth the good fellow, and in a trice I was in the tap-room.

I drained a flagon, threw a zechin piece to mine host, and was back on my snorting steed ere my trusty henchman had yet finished his speech. (But i’ faith I was ever of honest intent, and I must admit to thee, that Jack Pudding was a fearful stutterer.)

On we went, through the wide street, and ever and anon a straggling irregular line of lamp-posts jostled and bumped each other as they marched to meet me.

But this stag at eve had drunk his fill, and I well knew that on such occasions the lamp-posts were all unblameworthy.

As the thunderous strokes of Big Ben’s hammer pounded twelve, I drew rein at Blue Devil Falls, and dismounted. Don Giovanni Ziffkoffsky arrived in two seconds, with two seconds.

“Well met, villain,” I cried, as I whipped out my blade, “art ready for the fray? As for me, on foot or horseback, on the Eiffel Tower or the crater of Mt. Vesuvius, with spear, axe, sword, lance, tomahawk, or bullet, I am alike ready to encounter thee.”

Don Giovanni turned pale, but he clinched his shaking, trembling fingers, as he said:

“Why so choleric? Art excited at the outlook? Behold me, I am as cool as an iced cucumber!”

“Cool?” cried I, in derision, “aye, cool! Thou’rt cold,—with fear and apprehension! And well may’st thou be, for ne’er again shaltst thou hear the crash o’ the breaking day, and the fair moon above us looks down for the last and final time on thine upright form.”

“Pish! Tush!” cried the Don; but he tr-r-r-embled as he spake, and weary of this worthless war of words, I cried:

“To the battle-ground! En avant!”

The tight-rope had already been stretched across the rushing, roaring cataract, and simple Jack Pudding wept as he saw the fearful chasm abyssing itself beneath the fine, frail strand. And sooth it was a fearsome sight! A terrific thunder-storm had set in, and inky masses of black, pall-like clouds jostled and bumped each other in the heavens with thunderous noises as of loud artillery. Crashes and flashes vied with each other for frequency, and the rain came down in hemstitched sheets.

Ere the duel began, the Don and myself were inspected, lest, forsooth, concealed weapons be found upon us.

“What hast thou bound about thy right arm?” the color-sergeant said.

“Sirrah,” quoth I, “that concerneth thee not. Have a care, or thy curiosity will meet its meet reward.”

So saying, I adjusted the dainty hoop-skirt of the fair Lady Berenice, and gazed down at it with a proud devotion.

“The Fiend take thine impudence,” the color-sergeant said. “Answer, by the card! Is ’t a coat of arms?”

“Nay, Varlet!” I cried, and I had much ado to restrain my angry sword, “ ‘tis a petticoat of arms, and ‘tis not for thee to learn further concerning matters beyond thy ken.”

A loud shout from the spectators, and a waving of bandannas greeted this speech, and I felt that the sympathies of the packed galleries were all mine own.

“Swords?” said a lackey politely, and offered a short and a long blade for my choosing. They were noble weapons, and I yearned to take both that I might make the long and the short of one villain in double-quick time; but this was not allowed. However, I thought, of two mediævals the less is always to be chosen, and I grasped the smaller sword.

The boom of a cannon recalled to my mind that ‘twas time the game was called.

“En garde!” I cried, lightly running out to the middle of the tight-rope; and, pausing just above the roughest, ruggedest, rockiest of the raging rapids, I turned and faced toward mine enemy.

Don Giovanni Ziffkoffsky came to meet me, but slowly, for he was of monstrous girth and vast amplitude, and the rope creaked with his weight. Then we had at it! Zounds, what a fight it was! Tierce! Quatre! The Don lunged and I parried. He ran me through and I feinted; he foiled my thrust, I thrust aside his foil. The strokes of steel rang out between the crashing thunderbolts, and the blade-struck sparks rivalled in fiercity the lightning’s livid glare.

I had no mean antagonist. The fury of his onslaught would have vanquished any mere champion.

Don Giovanni was a skilled swordsman. One after another, he had killed the great duellists of the world. On his breast hung a hundred gold medals, first prizes from numberless expositions; and these, between which my sinuous blade must needs thrust and curve most dexterously, rendered more limited my striking space, though there was still much left. Aye, Don Giovanni Ziffkoffsky was a fierce assailant, a pre-eminent sabreur, an unparagoned tactician, an unparalleled techniquist, an inimitable, unapproachable, incomparable combatant, but—I was his superior! With a marvellous clever backward side-thrust, a stroke of my own invention, and one that has ever stood me well, I struck his blade from his hand and hurled it a mile away into the forest.

“On guard!” he cried (he didn’t know French), and to my shocked surprise he jerked from his jerkin a pistol, which he aimed full at my face.

I secretly gave myself up for lost, and my heart flew, even as a swift shuttle between my throat and my boots.

But naught of this did I reveal to the gaping curious throng of onlookers. With a fine show of carelessness, I shrugged my shoulders, and as a thunderbolt like the crack o’ doom split our ears, I said nonchalantly, “I hope ’twill not sour the milk in my pantry, on which I sup to-night.” But, though apparently thoughtless, I earnestly scanned about me for help.

And not in vain, for my staunch friend and true forsook me not.

Even as I despaired came whizzing toward me a revolver, loaded and cocked, flung by the firm hand of my firm friend, good Jack Pudding.

I caught the weapon, and ’faith ’twas none too soon, for the Don had fired and his bullet had already travelled half the short distance between his smoking pistol and my brain. Now though I be an adept at sword-play, yet have I even more marvellous skill as a marksman, and aiming with careful eye, for it was a matter of nice adjustment, and required, moreover, careful calculation of meteorological conditions as well as an astrological knowledge of the conjunction of the planets, I fired at the advancing bullet.

As I had intended, the conical bullets impinged, but by such a hair’s-breadth that their respective courses were only sufficiently deflected to make them whiz harmlessly by our left ears and sink deep in the mud-banks on either side of the river.

“Thou ’rt the Fiend’s Own!” exclaimed the Don, “a murrain take thee for a Blue Devil thyself! Have at thee, then, with bow and arrow! Art archer as well?” The Don smirked triumphantly, little dreaming of my mastery of the feathered shaft, but I only said :

“My archery is but indifferent; however, sith it please thee, let’s to it.”

My heart misgave me a bit, for though I had all confidence in my skill, yet had I a felon on my thumb which greatly impeded my drawing of the bow-string. And so my shaft flew awry, and long, long afterward in an oak I found that arrow, still unbroke.

My opponent had aimed surely and well, and as his arrow came flying toward me my calm was a bit disturbed. In dumb despair I watched it coming, but after it had traversed about half the distance between us I noticed it was speedily swerving a trifle to one side. I was saved, and that by a marvellous strange happening!

I chanced to have an apple in my pocket, and, as all the world has known since the days of William Tell, it is a scientific fact that an apple draws an arrow as surely as the magnet attracts iron.

Inevitably, irrevocably, and unavoidably the Don’s arrow was drawn to my pocket and buried itself in my life-saving apple! With sublime unconcern I took the fruit from my pocket, dislodged the arrow, and cast it into the falls, and tossed the apple into the spectating crowd, who fought for it as a souvenir.

“Thou lown! thou runnion!” cried my adversary, purpling with rage and mortification, and dancing about until the tight-rope slackened. “Come on, with fisticuffs will I conquer thee! Hand to hand will I engage in this tug-of-war, and by the bloody blade of Bellona, the heavyweight shall yet ride cock-a-whoop over his routed, flouted foe! Aye, Sirrah, pride must have a fall, and soon shalt thou bite the dust in the plashing fall below.”

Now, though small, I was a skilled boxer, and a little boxer is a dangerous thing. But of a sudden I realized that my strong right arm was hampered by my lady’s love-token. By some mischance the ribbon that bound it in place had loosened, and the intractable, well-nigh unmanageable hoops were rioting madly in unexpected directions. I grasped, I clutched, I grabbed, I twisted,—the more I stowed it away the more there seemed to be of it.

Should I have at him, regardless, and chance the twisting, squirming thing to throw us both off our none too secure balance? Or should I cast off the token and let the black rapids carry it away forever, trusting that my lovely Berenice would prefer my living disloyalty to my fatal fealty.

But I dismissed this thought as one unworthy a lover and a Kildare, and after mature reflection I hurriedly decided there was but one thing to do.

And so, as my pugilistic antagonist raised his right arm to fell me to the fall, I shot a glance at him which pierced his heart.

He staggered, swerved, tottered, stumbled, and I saw his huge body fall over the side of the tight-rope.

But, to my incredible surprise, he did not fall from the rope. His feet remained fastened to the straining hemp, and a brief examination soon revealed the cowardly truth.

Sticky side out, he had covered the soles of his shoes with fly-paper!

With lightness skipped I off the tight-rope, albeit I forgot not to make pretence at stumbling, as the time-honored tradition of the best tight-ropists hath it, and all unwaiting for the plaudits of the populace, I set off with hot speed to my Lady Berenice.

As I neared the feudal castle where she abode, I gazed with admiration at the great pile of sculptured granite which rose so majestically from its moats and terraces.

I cantered into the courtyard, crying, “What, ho!” and a liveried lackey bounded forward to take my horse.

Ushered in, betimes, I traversed the vaulted, tessellated corridors, and reached at last my lady’s presence in the Turkish tea-room.

Though feeling pretty bobbish after my triumphant despatchment of the dastardly Don, i’ faith I felt a bit phased at the grandeur and luxury betokened by all about me.

My heart sank, my temperature fell, and my jaw dropped, as I realized the fierce obstacles that sprang at me, open-mouthed, and threatened to swamp me.

But bravely crushing down my depressed spirits, I advanced to meet my adored one.

The fair Berenice, fairer than ever, in white satin and pearls, with a court-train of yellow velvet, smiled at me shyly over her peacock-feather fan. In her beautiful hair was a waxen blossom of the Magnolia grandiflora, and at her breast was another bunch of wax flowers.

“Radiant Rose of Loveliness,” I began, for well I knew that a straightforward simplicity of speech is ever the best way to win a wayward, winsome heart, “deign, I beseech thee, to cast a glance on thine humble slave, who, kneeling low at thy feet, craves thy kindly favor. Thy miscreant bridegroom is no more. At my bidding he bade farewell to earth, and mine it is to woo his witching widow. Say not I am too previous, say not this is so sudden, for I, thy lover, am of an impetuous impatience, and ’tis my intent to seize Time by the lovelock.”

The Lady Berenice parted the feathers of her fan and peeped coyly through at me, saying “Dost love me?” in such dulcet tones that I had much ado to refrain from crushing her to my manly bosom. But I was ever dignified of mien in my love-making, and, too, I had no wish to spoil her bunch of wax flowers.

“Aye!” I replied, in a thrilling whisper, “I love thee with a love unknown to the most noted lovers, unheard of by the ballad-mongering herd. Compared to my adoring passion, Romeo’s was but a passing fancy, Abelard’s only a friendly interest, and Orpheus’s a mere casual acquaintance. For thee would I die a thousand deaths, and welcome each as the parched earth welcometh the rain. Tell me, Angel of my Vision, has the torch of love ignited thy tinder heart? Dare I hope that thou art mine, as I am thine?”

For answer the Lady Berenice stood speechless, but with an unmistakable love-light shining forth from her glorious gray orbs. Then I heard her sigh, a low, tremulous, happy sigh, like the sneeze of a wheezy snail, and with a sudden fling she flung herself into my waiting arms, and exclaimed in accents of affection:

“My own! my owner! my ownest!”

Need I record that when next I saw the wax-flowers they were a shapeless, molten mass?

After a period of such ecstasy as is known only to the heroes and heroines of the six best-selling books, my adored one said softly:

“Tell me now, my True-love, of thy noble home, of thy Halls Baronial; thy towering castles, with their castellated towers, where the rooks roost in the pinarets. Relate to me of thine illustrious family, thy dowager lady-mother, and thine august sisters.

Anon at these words came a great change to the visage of Claude Kildare.

To his bones turned he white, and his hair stood up on one end. His flesh crept, his blood ran cold, and, struck all of a heap, he stood aghast at the fearful predicament in which he found himself. But, though trembling at every pore, he screwed his courage to the sticking-point, marched up to the cannon’s mouth, took the bull by the horns, and let the cat out of the bag.

“Lady Berenice,” he said, and his voice was as limp as a wet blanket, “Lady Berenice of Bois-Bracy, as I stand in thy presence, I am in the Slough of Despond and the Cave of Despair. Alas, alack-a-day, and woe is me! Would that I could spare thine ears the recital of my guilty secret, but Truth is mighty and would sooner or later prevail.”

“Ha!” said the Lady Berenice.

“Ha, indeed!” returned her lover. “And list thou now while I my tale unfold. Of a truth, fair maid, I am not what thou thinkest. Ancestral acres are not mine to boast. Patrimonial possessions have I none, but matrimonial possessions I trust will make good the lack. Thou lovest me, and therefore, thine is mine. For know, my Fair One, thy lover is no belted Earl or buckled Baron, but a humble, lowly, ignoble, plebeian bricklayer.”

A fleeting flush flamed in the fair face of the Lady Berenice.

“Avaunt!” she said, “avaunt!” After an anxious pause of mayhap ten minutes she said “Avaunt!” again, and then repeated it.

“Aye!” hissed Claude Kildare, bitterly. “My certes, but thou art the uppish Upstart I deemed thee. Thy knavish race is ever ill-disposed toward an honest, humble yeoman. And yet, have a care, my proud and haughty Beauty, the day shall yet come when I will requite thy scorn with scorn, and with thine own contempt will I contemn thee! Aye, by my Halibut! sorely shalt thou rue this day!”

The Lady Berenice was touched, and with a gentle, patrician gesture she drew a silver ruble from the silken pouch at her side, and bestowed it upon her lover.

“Fair guerdon from a fair hand,” quoth the recipient of this bounty, as he pocketed the gold; “and it shall go hard with me, but I gain the giver as I have the gift.”

With this unutterable threat Claude Kildare arose, and his measured tread resounded hollowly as he strode around the four sides of the great apartment.

“Long years of yore,” he said, as if meditating to himself, “I heard of thy far-famed beauty, and I vowed to win thy hand if by fair means or foul. To this end I assumed the name and fame of Claude Kildare. But now,—now that I have won thee, I dare not hold to the claim, for I have no proofs; I cannot lay hold of the Kildare acres, I know not where they are. I may not show thee even tintypes of the portraits of my Kildare ancestors, I know not where to look for them. But thou crossed’st my path, thou met’st my advances; indeed, thou fairly threwest thyself at my head, therefore, I now cast myself at thy feet.”

Suiting the word to the action, Claude Kildare with a double somersault landed gracefully on the red Brussels roses at the feet of Lady Berenice.

“Claude,” she said, “Claude,” and her voice was soft and sweet as a ripened canteloupe,—but with a glance of mingled terror and horror he gasped in a hoarse, harsh whisper, “Not Claude!”

“Mr. Kildare,” she began, misapprehending his meaning.

“Nay,” he moaned, “not so. None of those is my rightful name. Ah, Lady Berenice, how shall I tell thee? My name, my rightful, my frightful name is—Abeniki Caldwell!”

With a fearsome shriek the Lady Berenice fainted in the arms of her stalwart suitor.

Whether the sudden and, as he hoped, temporary cessation of an intelligent use of her faculties was due to the Lady Berenice’s surprise tinged with regret, or regret sharpened by surprise, Abeniki Caldwell never was able fully to determine, for he had scarce an hour in which to meditate uninterruptedly on the matter, when, with a sigh and a quivery shiver, the lovely eyes opened their blue depths and widths, and the Lady Berenice came to.

“Ah!” said the well-nigh distraught lover, gazing raptly into the fair, flushed face of his enchantress.

“Ah!” she replied.

“An thou lovest me the same?” he queried gently.

“How is it spelled?” she asked; and though it was a difficult task, he spelt Abeniki for her as well as he could.

“ ’Tis a rare, precious name,” she averred, “and fain would I accept a lover thus dubbed. But the Caldwells?”

“Aye, the Caldwells,” repeated Abeniki, of that race, “a brave and brawny house, forsooth. A hardy clan, any of whom could fight single-handed the Barons of Bois-Bracy and destroy them one by one. ’Sdeath! the Caldwells be a mighty race, a boisterous, blustering, burly race, and they put to shame thy puny, puerile ancestors! Ha, Lady Berenice, would’stn’t rather have a doughty daredevil to thy husband than a dandy duke?”

Although the daughter of a hundred earls, the Lady Berenice was so impressed by this talk that her patrician principles were swept away as by a whirlwind, and she answered, with the meek modesty so becoming a woman:

“Aye, sir.”

“Then thou art mine!” cried Abeniki Caldwell, in enraptured tones. “Come to these waiting arms, my Lily of the Desert, my Rose of the Ice-Bound Sea.”

Like a trembling oriflamme the fair Lady Berenice swayed toward him, but ere she rested her tiaraed head on his armored bosom, the portals of the apartment parted and a stern, stentorian voice cried out in accents dire:

“Cur, coward, caitiff! what dost thou here? Thou pagan dog, darest thou lift thy wormy eyes to a scion of the House of Bois-Bracy? The curse of St. Hamako be upon thee! Thou art a fish and the son of a fish!”

“My father!” shrieked the Lady Berenice; and breaking away from her lover’s embrace, she broke into a flood of weeping.

“Jade! minx! cease those tears!” commanded the enraged Baron; but at this his disobedient daughter only wope afresh.

“Hist!” said Abeniki Caldwell, and though ’twas but a whispered word it echoed with a steely glitter through the resonant archives, and caused the Baron’s soul to shrink to the size of a shrivelled pea.

“Hist!” the young man hissed again, and the Baron, frenzied with fear, tremblingly cowered in a towering rage, and histed.

It was a strange encounter. The Baron, a nobleman of some twenty years’ standing, sat down as he faced his plebeian antagonist. The old man’s face was seared with the lineaments of high birth and breeding, and race was clearly denoted in every one of his long whiskers. His silvered locks tossed nobly above his patrician brow, and his august nose betokened an unbending hauteur.

But his malicious, menacing glance was met by one equally terrifying. Abeniki Caldwell, a son of the people, two of them, a layer of bricks and a hewer of mortar, was a plebeian of low class, yet withal of a high temper. Although but an outcast, he was cast in a heroic mould, and so was of no mind to accept other than the hero’s rôle. He gazed at the Baron, a suave, sinister smile curving his chiselled lips beneath his marble brow.

A pause ensued, and then, picking up the silence which had fallen, Abeniki, with one eye on the Baron and one on the Lady Berenice, thus spake:

“Baron though thou be, nobleman though thou art, I disdain thee! The crawling slug rises in red rebellion against the mammoth mastodon and hurls defiance in his teeth under his very nose! Aye, even I denounce and deject thee! The time shall come—for so it is written—when Abeniki Caldwell shall triumphantly trample on the prostrate glories of the ruined house of Bois-Bracy.”

“Ha!” ejaculated the panting Baron.

“That may be!” thundered Abeniki, “but by the Holocaust of the Hyperion, thy doom, thy fatal doom, is sealed. Thy towers shall totter, thy turrets tremble and tumble, and ’mid the crashing din of destruction I shall return—return, and, grappling with incarnate horrors, rescue my love, my Lady Berenice.

“But on thee, foul-hearted traitor of a falsehearted race, the dastard doom shall descend,—the raging elements shall engulf thee, and a roaring, rushing torrent of seething flame shall hurl thee into a blazing, fiery pit, black with the pitchy, Stygian blackness of thine own scurvy, sinister soul!”

Now leave we off discoursement of the bumptious Baron, and speak we concerning the further adventure of Abeniki Caldwell.

When that the fair knight neared the tryst, all waiting sat the lovely Lady Berenice.

“Gramercy Park!” exclaimed Abeniki, “but of a troth thou art a golden vision!”

And he spake true, for never, I ween, might there be a more handsomer or better bedight lady.

Her pale poplin peplum, caught up with a jewel-bestud belt, disclosed a petticoat of pink Paisley, while round her regal shoulders was wrapt a red raglan.

“Adored of my Heart,” began her impetuous suitor, as, kneeling, he kissed the earth beneath her feet, “meseems thou art distraught. The pale cast of thought sicklies o’er thy radiant countenance, and fain would I know the cause.”

“Alas,” quoth the lovely lady, tears dripping from her liquid orbs, “all too well knowest thou what cloud o’erdims my roseate future. I, a Berenice of the Bois-Bracys, may not wed with a bricklayer and a Caldwell.”

“Now, by the gabardine of St. Archibald, this passeth all patience!” cried Abeniki Caldwell in a stormy wrath. “To my reasoning a man may wed whom he will, an he but love her. What meaneth a paltry ancestral line? This marvel eludeth my ken, and I would I could see with thy vision!”

The Lady Berenice lifted her eyes to her lover s face, but he returned them tenderly, with a caressing gesture, and murmured:

“Nay, Fair One,—but list thou now to me. Mayhap I be of humble origin, perchance ’tis not mine to wear a Baron’s hauberk, or an Earl’s baldric, but ere yet again the zodiac shall round the azimuth, Abeniki Caldwell shall proclaim himself a prince, a royal prince of the Blood!”

“And how wilt thou compass that?” asked the Lady Berenice, her fair brows wrinkled with wonder and interest.

“How me no hows!” exclaimed her lover. “I go, but I return—re-tur-r-n. And so, my Betrothed, my Bride-To-Be, adieu for the nonce, but no longer. Adieu, my Amiable One, my Adoration. Sit thou there and await me, for as a prince I shall return, either with my train or on it. Adieu, adieu, and, without more ado, adieu!”

With admiration and adieu depicted on every lineament of her fair face, the Lady Berenice summoned her two female attendants, and as Caldwell’s ship fluttered away from the shore they bade him a hearty good-speed and waved a fond farewell.

My sweet adored one stood high on a sand-dune, and spied me through her spy-glass until I rounded the horizon and was lost to view.

As I sat on the hurricane deck I cogitated deeply in thought. On flew my staunch ship over the deep, dark, dank waters, and on flew my troubled mind across the days and months and years which must, perchance, elapse e’er I returned, a prince and a nabob, to claim my Love, my Berenice.

How I might manage this I had no notion. But in the humble heart of a bricklayer surged the noble yearnings of a prince, and well I knew I must come into my own at last. It was, forsooth, uncertain whether I would choose to be a changeling prince or a victim of mistaken identity. If both these politic schemes failed I had but to usurp the rights of some well-to-do prince, and trust to my dithyrambic fate to carry me through.

Be that as it may, I sat on deck that golden-gray evening thrilled with the throbbing throes of a love that should yet be blessed, and experiencing no premonitions of the wild and woolly hap awaiting me, I thought with a deep thoughtfulness on the beauty of my radiant Lady Berenice.

Zounds, but she was a jewel of a woman! Her teeth of pearl set ’twixt her ruby lips; her marble brow and alabaster neck; her shell-like ears, half hidden by her gold (plaited) hair; her sapphire eyes with their jet lashes, shedding diamond tears at my departure! And to think she should be so unattainable, so far above me. But I vowed to change all that. I swore I would yet be her equal, and things which are equal to each other are equal to anything.

Anon after that, Abeniki Caldwell sat moody on the quarter-deck of his swift-flying shallop. Rearing and plunging, the noble vessel forged ahead, leaving a wake astern, and as Abeniki paced the boom the ship rolled and surged on an even keel.

“Ha!” he thought to himself, muttering in monosyllables, as the black, bleak stars glowered at him from the murky heavens, “ha! the hour shall yet come, the day shall yet dawn in its splendor, when those same stars shall illumine the subterranean tombs of my noble ancestors!

Aye, when Abeniki Caldwell shall flaunt his patrician birth and breeding in the faces of his tormentors, while they hide their heads for very shame. Then will I espouse my beauteous Berenice, and brave, for her fair sake, the fifteen discomforts of matrimony!”

Having hissed these words, Abeniki flung his gray gabardine three times over his shoulder and strode swiftly amidships.

Why, do you ask? Ah, question not the deeds of a desperate man. Even though his heart was suffused with the radiant remembrance of his liege lady, even though his massive brain was all agog with the unfathomable problem he had set himself to solve, even though his thoughts were absorbed in the abstrusities of transcendant issues, yet such was the tensely-strung nature of his marvellously observant mind that Abeniki Caldwell smelled smoke. And that none too soon. As he sauntered toward the taffrail the decks burst into a lurid blaze, and though many ran hither and yon, none paused to acquaint our hero with the details of the disaster.

Now it so came about that though all disdainful of other elemental dangers, though fearless and careless of flood, earthquake, or tornado, Abeniki Caldwell had a congenital horror of fire. Oft had he travelled miles to experience the delights of a terrestrial fissure; a torrential cloud-burst was to him but a trickling shower-bath; and in a whirling, sweeping cyclone found he peace and content.

Minding, then, I doubt not, a blind impulse rather than a diagnosed intent, skipping, as he were the Arch-Fiend on his own coals, with eyes alight and head aloft he bounded up to the hurricane deck, where raged a wild and wailing hurricane.

He felt the biting wind and realized that he was in the very teeth of the storm.

This was the night, black with the blackness of an ebonized Erebus, dark with the darkness of a black cat’s pocket.

Into this inky, pitchy, sooty, murky, fuliginous midnight gazed the glaring, glittering eyes of Abeniki Caldwell.

All triumphant stood he, motionless, though dancing about with excitement, and withal calm as a sleeping sloth.

He bruited his purpose to no one, but stealthily and surreptitiously looked from beneath frowning brows at his watch.

“The time is ripe,” he muttered, a sinister gleam dawning in his either eye, “aye, and over-ripe. All cautiously must I pick my time. But, soft! it now behooveth to set my quadrant.”

The delicate instrument being yarely adjusted, Abeniki Caldwell gazed with a bent face upon its revelations.

“Sith the secant equaleth the cosyhedral tangent,” he muttered, “then, by the rood, the spot is but equidistant. Ha! ’tis as I feared.”

In mad haste he seized an oar, and, leaping strident o’er the taffrail, he was, with all soonness, whizzing whirringly through the circumambient atmosphere.

On he sped, on and down, until, his traverse ended, he alit with safety on a bounding buoy.

Howbeit, he had great to-do to rest quietly on this coign of vantage, for so curved and wet and slippery was it that he must needs cling for the dear life he was preserving for his unknown ancestors.

Still was it cooler and pleasanter than the burning deck, and, as the hours struck, for it was a bell-buoy, Abeniki Caldwell clung right cheerily, when approached a monstrous shark all unfriendly of expression.

Though passing brave of heart, Abeniki could scarce prevent a slight show of irritation on his otherwise handsome, tranquil face. Then with a Delsarte gesture expressive of dire despair, he gave himself up for lost.

And, in sooth, to the casual onlooker the situation might appear somewhat strained.

But of a sudden, swooping downward with ravenous beaks through the blue air, descended a flock of sea-larks. Onslaught made they upon the Cyrano-nosed monster, until, for very pain and rage, was the shark forced beneath the waving water.

Whereupon the night fell; and as Abeniki Caldwell dozed in the darkness, so lost he his hold of the buoyant buoy, and, silently drifting, floated adown the tide.

All unnoting distance or direction, it ill beseemeth to say that ’twas with surprise he found himself at the dawn on a bleak and barren desert island. Uprearing his stalwart frame to a sitting posture, Abeniki Caldwell looked about. About what? you ask. About three and thirty, I reply, though, mark you, this is but of a rumor. Whose is it to say veraciously of the age of an unrecorded bricklayer?

The dawning day broke slowly over the serried Sierras, and the vine-clad hills cast trembling shadows on the mere. Snow-capped peaks rose majestically in the air and floated away. Hordes of wild animals bayed blatantly at the silent, hooded form, as, all unheeding, Abeniki plodded on.

But albeit his surroundings were all that could be desired, yet in the harrowed heart of the besom bricklayer smouldered ever and anon a fierce, blazing anger, the which he might not quell.

“Is a prince but a chaffinch?” he roared in dumb soliloquy. “Is it naught that I bear a panoply all unencumbered of danger or defeat?

Nay! a thousand times, nay! and by the Invincible Armadillo of the Aurelian Archipelago I vow to reach—aye, and to overreach my goal!”

Now leave we off discoursement of my adventure by sea, and turn we to the right marvellous prowess which befel me by land.

A many days I wandered among the bosky dells and jungle glades of the desert island, yet met I no man and eke no woman. Nor had I food. Wearily I trudged the rocky paths, cold and fatigue my bedfellows, starvation my playmate. Ever and anon my thought stole back to my lovely lady, and then more present dangers recalled me to myself.

Oft at the dawn would I wake in my hammock, slung high beneath the rays of the crescent moon, and gaze down into the open, hungry, yelping jaws of a dozen wild animals. And I but laughed at them,—aye, laughed; yet, withal, ’twas a mere mockery of a laugh, and rang but hollowly from my chattering teeth. Howbeit I made shift to stay ever in the trees when dangerous beasts stalked below, and being a man of well-ordered content, I fretted not nor fumed, though regretting sorely the delay of my quest.

But of a day it came to pass as I sat blithely on a branch, that it brake with a dire cracking noise, and, without more ado, downfalling, I descended to the open, upturned jaws of two Bengal lions.

Lions, did I say? Nay, I but jested,—the beasts were of more vengeful sort. A bear and a tiger met my astonished vision, and at their proximity was I sore provoked.

But I had at them, and did as bravely as it were possible a man to do.

The bear advanced and I smote off his head with my trusty club, then gripping the furious tiger by his furry throat I made despatchment of him with my cutlass. Thus, then, was the victory all mine own, and with speed I set off and walked on to the cabin.

Merrily strode I along and reached the rude hut in time to perceive two plain, hard-featured men busily laboring at their work.

“Hola, fair gentlemen,” said I, for I was ever polite and courteous of address.

The rougher, gruffer, and tougher of the two fellows turned his weather-beaten face to mine and handed me his card.

“Admiral Farragut!” read I aloud; “now by my troth we be well met. And how may thy friend be called?”

“Only with a megaphone,” replied the Admiral, “for, alack! he is of a stone-deafness. Hola! Hola!! Charley! Char-lee!!” he then shouted through his parenthesized hands.

The fellow turned, and I saw of a truth ’twas none other than Charles II. of England.

“Exiled, by Jingo!” I exclaimed, for my historic knowledge was great and impugnable.

“Aye,” Charles replied, “’twas indeed by Jingo, though not then so dubbed. Odspitikins, sore do I fear Cromwell’s dragoons will follow me e’en to this restful spot, this St. Helena, home of the exiles.”

“Marry!” quoth I, “and is this, then, the Isle of St. Helena, the Isle of the Exiles?”

A thousand fleeting thoughts flet through my brain. Could it be, might I dare hope, that Napoleon would be there? All tremblingly I put the question, and with bated breath harked for the answer.

“Aye,” said Admiral Farragut, and his rugged countenance seemed to lose a little of its rug, “aye, across yon firth he dwells. See’st thou not the smoke arising from his chateau chimneys?”

I gazed, aghast and aglow with suspended patriotism, then unbating my breath, I quoth:

“Noble Napoleon, Hero of the Heroless, all honor to thee and thy vicious victory at Valley Forge! Accept the homage of a nameless, fameless, blameless youth, and may’st thou evermore be safe from the savage Sheikhs and the snub-nosed Normans.”

At this sonorous and able peroration the two men had at me and made as if to shake me by the hand in approbation; but being ever of modest demeanor, I covered my eyes, saying, “ ’Tis naught, ‘tis naught!” and from that moment were we all fast friends. Farragut was faster than I, but Charles was fastest of the lot, and by the same token sat we down to devise our plans.

To it briefly, then. They had come to the island with full fell purpose of plundering and conveying away the gold and treasure deep buried there by Cossimbazar, King of the Incas.

“Odso!” quoth I, when that this had been vented unto me.

“Be that as it may!” cried Admiral Farragut wrathfully enough, “but know, thou Saxon yeoman, that my father was a Spaniard, and therefore on me and none other devolves the dastard duty of rescuing the royal rubies and grasping the graven gold!”

I consented outwardly enough, but a suffocating doubt eddied all miserably through my staunch heart, for full well I knew their merry badinage was but a cloak covering a deep, dark, and deadly plot to kill and assassinate me even at the even.