|

Project Gutenberg

Australia a treasure-trove of literature treasure found hidden with no evidence of ownership |

BROWSE the site for other works by this author (and our other authors) or SEARCH the entire site with Google Site Search |

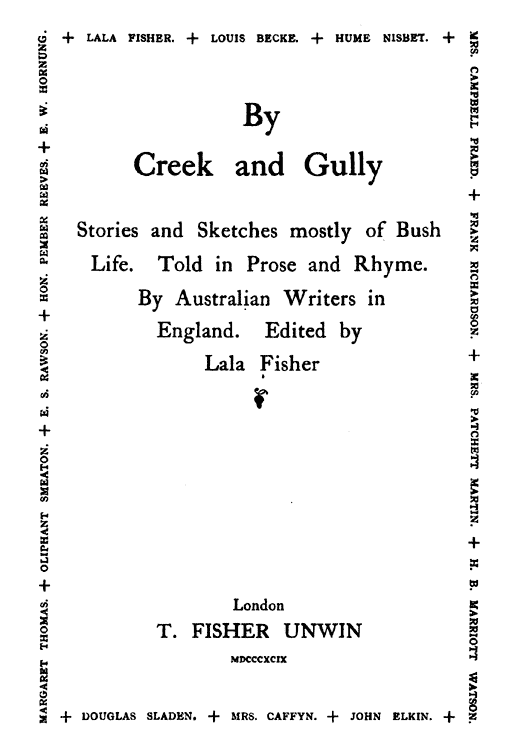

Title: By Creek and Gully Author: Lala Fisher * A Project Gutenberg of Australia eBook * eBook No.: 1701361h.html Language: English Date first posted: December 2017 Most recent update: December 2017 This eBook was produced by: Walter Moore Project Gutenberg of Australia eBooks are created from printed editions which are in the public domain in Australia, unless a copyright notice is included. We do NOT keep any eBooks in compliance with a particular paper edition. Copyright laws are changing all over the world. Be sure to check the copyright laws for your country before downloading or redistributing this file. This eBook is made available at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg Australia Licence which may be viewed online.

GO TO Project Gutenberg Australia HOME PAGE

To The Story-Makers ~ Lala Fisher

Cross Currents ~ Mrs. Patchett Martin

Papaitonga Lake ~ Hon. Pember Reeves

Point Despair ~ H. B. Marriot Watson

Struck Gold ~ Margaret Thomas

The Larrikin of Diamond Creek ~ E. W. Hornung

The Man From Bot’ny ~ A. Patchett Martin

His Luck ~ Lala Fisher

My Friends the Cannibals ~ Hume Nisbet

Lenchen ~ Mrs. Caffyn (“Iota”)

To My Cigarette ~ Margaret Thomas

A Sexagenarian Idyll ~ Oliphant Smeaton

Heimweh ~ Lala Fisher

The Inside Station ~ Douglas Sladen

What Did He Do With Them? ~ E. S. Rawson

The Old G. P. O. ~ John Elkin

An Australian Rose ~ Mrs. Patchett Martin

The Sleeping Sickness of Lui the Kanaka ~ Lala Fisher

The Old Scenes ~ Mrs. Campbell Praed

Last Cruise of John Maudesley ~ Louis Becke

“An Incident Out West” ~ Frank Rikchardson

When fairies weave a wizard spell,

And conjure up before our eyes

The days and scenes we loved so well,

And men and maids long lost arise—

When at their bidding camp-fires gleam

With boiling billy on the hook,

It seems so true and sweet a dream

The gazer nearer draws to look.

Up with the sun, we paddocks pass,

Where lazy bullocks lift their heads

To see us go, then crop the grass

That grows beside the dry creek-beds.

The stock-whip coils upon our knee,

Our pannikin is strapped behind;

We ride across the wakening lea

The lost and straying beasts to find.

The wary kangaroos close by

Are browsing when our nags draw near;

Alarmed, they to their joeys fly,

Who in a twinkling disappear—

Disdaining haste—with measured bounds

They vanish o’er the distant hill;

We whistle back the eager dogs

So thirsty to pursue and kill.

Once more the crystal creek we breast,

Showering its pearl-drops high in air;

We part the rushes, see a nest

Of ducklings golden hidden there!

While fairy fish in glittering flocks

Dart o’er the pebbles blue and red,

A kukaburra laughs and mocks,

Safe in a gum-tree overhead.

Now slowly forging up the track

The tired musterer returns;

His hanging head and bended back

Above his horse one scarce discerns.

His idle reins no touch await

To guide or check the patient steed,

Who stops beside the homestead gate

To pull a switch of swamp-grown feed.

Then over all a tender light

Slow settles as the sunlight dies:

The tree-tops catch its misty white

Ere yet upon the land it lies;

The flowers know it and are glad,

The breezes meet it with a sigh,

The bushman sees it and grows sad

And thoughtful, though he recks not why.

‘Tis night! how still the bush has grown,

With sentinels of ring-barked trees;

The ghostly stars give light alone,

And mournful whispers fill each breeze!

A lonely ‘possum steals along

And lightly passes to its nest,

A sleepy mopoke drones a song,

Then the vast land sinks into rest.

A magic power indeed ye hold

Who wield the sweet, enchanted pen;

To more old hearts than could be told

Thou bringest back life’s youth again!

Beneath thy thrall hopes blossom fair,

The soul’s regret forgotten lies,

With lagging wings afar flies Care,

And Joy beams forth from happy eyes!

WHEN Alma Belmont arrived at Bristowe she had done about as foolish a thing as any young woman of four-and-twenty could have done in the way of marring a life that had been only too pleasant. Spoilt as a child, indulged in her wilful, wayward fancies as the only daughter of a long-widowed parent, much petted and admired in the set in which she moved, she had elected to consider herself an ill-used and unhappy creature, and had impulsively and hurriedly married a man who had come to her one day with a plea to “save him from going to the devil, for she was about the only woman who could do it.”

The excuse she made to the world was her father’s second marriage; to herself the impossibility of marrying the “only man she had ever really loved,” and a kind of pride in the thought of reclaiming a poor fellow who loved her from the error of his ways. She was able to impose upon herself perhaps more successfully than on other people, who failed to see that a rich stepmother who “entertained,” and did her duty by society and marriageable maidens, was other than a highly estimable person, or that, as far as Alma herself was concerned, her devotion to a girlish ideal had ever stood in the way of many flirtations and a very patent enjoyment of her ballroom triumphs and successes. As to reclaiming Captain Belmont, the utter fallacy of such an aspiration revealed itself to her in the early days of her marriage, which were spent on board ship on their outward voyage to Australia.

He was one of those gentlemanly and agreeable ne’er-do-weels whom other men characterise as “no man’s enemy but his own,” who had a “taking” way with women, much superficial good-nature, and an utter absence of principle. Withal, not destitute of a certain kind of cleverness, and possessed of a winning, almost boyish, affectionateness, which made his own womankind very gentle and tender and forgiving towards him, until came those evil days when he had sunk so low that even they could forgive and tolerate him no longer.

It is not, however, the story of Alma Belmont’s married life that I have to tell, though it would have furnished material for a three-volume novel, but merely to relate an episode which did not even indirectly concern her husband, who had gone “up country” at the time in quest of one of those vague and frequently mythical “appointments” which he was very fond or talking about, and which entailed much acceptance or hospitality and even of monetary loans from genial hosts and open-handed Australian acquaintances, whom the plausible and quick-witted Irishman won over by his gift of ready speech and the inventive powers that never failed him.

On this occasion, however, the “appointment,” which was “something in the Customs,” was genuine, and Alma Belmont was on her way to the northern town of Stony Hollow to join her husband, who had preceded her, and who was staying there with a relative holding a position under Government.

Stony Hollow was reached by a three days’ sea and river journey from the capital, from whence the high Customs official, who had held out a helping hand to the young couple, had seen Alma on board the steamer, with the kindly information that he had requested his brother collector at Ellenborough, where the vessel stopped for a night to take in and discharge cargo, to find her out on board, and thus make a break in the loneliness of her solitary journey.

It was in summer time, and every mile that they sped northward but increased the stifling heat and discomfort of the passage. It had been rough in the bay, there were even waves in the big river, and Alma had been seasick and was very miserable.

A wretched little six-weeks-old kitten, which her husband had requested her to bring for his cousin’s children, had added to her misery by its piteous refusal to drink milk that had turned sour, and she was every moment expecting the poor little thing would die in the stuffy basket in which she had brought it so far at much personal inconvenience. The premature demise of a baby kitten may not seem a trouble to distress one’s self about; but the lonely young wife was in that condition of forlornness that she had almost grown to care for her little travelling companion, and the stewardess’s openly-expressed opinion that she couldn’t think how any one could have troubled themselves with a “common little tabby kitten” quite grated upon her feelings.

She had been reviewing in her mind all the circumstances that had attended her short stay in the colony; how they had landed with no possessions beyond the clothing in their boxes and a ten-pound note, half of which had gone to pay the laundress for washing the linen that had accumulated during the hundred days of their long journey in a sailing ship. She dwelt on the dismay with which she had contemplated the plethoric linen-bag and the attenuated purse, and the joyful surprise with which she had accepted a kindly hospitality proffered “until they could turn themselves round, and Captain Belmont should find something to do.”

They had not only “turned themselves round” pretty frequently in the pleasant riverside home of their kind entertainers, but had even gyrated in the viceregal precincts, and assisted at balls and receptions at Government House, where Captain Belmont’s waltzing and Mrs. Belmont’s pretty French frocks had come in for a fair share of admiration. Several things had been found for Captain Belmont to do, but his doings had been of a perfunctory nature, and the illegible scrawl on which he rather prided himself had not advanced his position in the Government office which he had honoured with a trial. “Set of scribbling cads!” was his remark to his wife. “Ought to think themselves d—d lucky to have a gentleman amongst them.”

Alma did not feel very sanguine as to the appointment in the Customs, and she was looking forward with nervous dread of the unknown life to which she was going, the unknown connections whose house they were to share, and the very slight prospect of any permanent home of their own being ever provided for her. She was tired of living with or upon other people, and this shuttlecock state of existence was highly distasteful to her. Stony Hollow, too, from all accounts, was not exactly the place one would select for a residence in summer, being built down in a basin and surrounded by a range of low hills, which were quite high enough to exclude all air from the dwellers in its midst. So her musings were not of a very pleasant nature as she sat alone in her deck chair watching the sunset until it grew dark with the sudden darkness of a sky that has no twilight. Cockroaches were beginning to issue forth from the nooks and crannies in which they had lain concealed during the day, and as the ship made its way up the river through narrowing banks, on which the dismal mangrove grew thickly, the large spotted mosquito which haunts these shores deserted the accursed shrub that gives it shelter to settle about the ship and on its sweltering denizens.

They were nearing Ellenborough, where a halt was to be made during the night to discharge and take in cargo, the new goldfields that had lately been discovered a few miles from the township having given it a commercial impetus which warranted the delay, even in the case of a vessel that called itself a passenger steamer. They had now reached the landing-stage; ropes had been made fast to the piles with the usual accompaniment of “Heave away!” “Hold fast there!” and “aye ayeing;” and the Custom House officials were stepping on board. Amongst them was a tall, slender lad with a profusion of brown curls tumbling out from under his straw hat, who accosted the captain, and to Alma’s astonishment at once asked if “Mrs. Belmont was on board.” When directed by a wave of the hand towards the lady in question, he came straight up to her, and as he raised his hat with a courteous gesture, introduced himself as “Athanase Bingham.”

“My father, you know, is the Collector of Customs here, and Mr. Thornhill, of Bristowe, asked him to look you up. My mother charged me to bring you to the house to supper, and to say that you must not think of going back to the steamer to-night, as there is a bed at your disposal.”

“Indeed, I shall be only too glad,” responded Alma, hastily adjusting the small toque she wore, and rising from her chair to follow her young visitor, who carefully assisted her to land, walking some distance along the quay and leading the way through a small gate that opened to the wharf, from an enclosure in which stood the Custom House. Passing one side of the building, and along the wall of a covered passage that seemed to connect it with a low, one-storied, verandahed dwelling-house, they found themselves in a garden, through which they passed, entering the house through a broad French window opening out on the verandah into a large, untidy, and yet comfortable-looking room, that revealed the harmonious life of a family by its combined masculine, feminine, and boyish litter. It was imperfectly lit by a lamp on a centre table, and at first Alma could but dimly discern the figure belonging to a rich voice that greeted her in foreign accents.

“Be welcome, my dear young lady, and excuse me that I do not rise. Nasi, approach that fauteuil. Bon. Now sit down by me, my dear, and remove your hat. Ouf! what a heat!” The speaker was reclining on a fully-extended cane lounging-chair, fanning herself with an indolent, rythmic movement. She was a large woman of about forty years of age, and must have been handsome till she grew stout; her massive proportions, that were evidently untrammelled by any corset, were exaggerated by the shapeless white cambric robe she wore, and masses of waving brown hair were hanging loosely by the side of her face, escaping from a thick twist coiled low down on her neck.

Alma Belmont’s first impression of the lingering, liquid tones that had greeted her was almost effaced by this superabundant and untidy vision, but presently she spoke again, fixing on her visitor a pair of soft, sleepy brown eyes that matched the voice to perfection.

“Chère petite, what a ridiculous little hat is that you have there! Your pretty fair face is all brown and burnt, and your poor nose—those terrible mosquitoes, how they have arranged you! Nasi, fetch the eau de Cologne, and a soft mouchoir, and dab her face; doucement, you know—but first, come and kiss your mother.”

The tall lad came to her and leant over her chair, and his brown curls mingled with her luxuriant brown tresses. As he left the room, she half raised herself and turned to Alma, saying, “Ah! no one can tell what a son that is! I had so longed that my little child should be a daughter, for I had one son already; but he is son and daughter both, ce cher Nasi!” The subject of her eulogy here appeared with the eau de Cologne, but did not attempt the dabbing process recommended by his mother, who sent him again out of the room on a fresh errand to see and report if the evening meal were ready. He returned presently with his father, a quiet, gentlemanly man of middle age, whose thoughtful face bore traces of disappointment or dissatisfaction with life generally, that showed themselves in the lines on his forehead, and in the querulous tones of a thin voice. Of the Irishman, nothing, no accent, no vivacity, nothing but the name. With a courteous allusion to the introduction of his friend, the Collector of Bristowe, he gave Alma his arm, while Athanase dragged his mother up from her reclining posture, and they went into an adjoining room, where a cloth was laid with cold meats, fruit, and salad, cakes, tea, and lemonade, and adorned with flowers. Alma’s head was aching frightfully, and she did but scant justice to the appetising repast, though it offered a delightful contrast to the greasy, ill-served meals on board the steamer. The little party had been increased by the addition of a good-looking boy of twelve, who, with his head resting between his hands and his elbows on the table, had appeared on their entrance to be completely engrossed by a book he was reading.

“This is our scholar,” said the father, with a glance of affectionate pride. “Our baby, too,” interposed the mother, who seated herself between her boys, while Mr. Bingham and Alma completed the circle at the round table. The hospitable hostess expressed herself au désespoir that her guest could not eat. Mr. Bingham said little, but his inquiries about books, politics, society “at home,” all showed a hankering after the old country. It was easy to see that the duties of his life were not congenial, however close and dear were the home ties of the family. Alma could not restrain a sympathetic feeling of pity for the man who had probably hoped for and anticipated a very different career, while at the same time, surrounded by this soft atmosphere of home, her pity for herself grew stronger, and she envied the lot of the happy wife and mother.

Rising from the table, Mr. Bingham said he had “some work to do”; the studious boy was going to “help his father with his accounts,” and the two ladies and Athanase adjourned to chairs on the verandah.

“Ah! but they are clever, my husband and Sosthène,” said the Creole lady, “and Nasi here is my dear, good boy, and my eldest son, Hilarion, who is away, is beau comme Apollon.” And so she babbled on with her simple talk, little knowing that she was planting daggers of regret in the heart of the girl who had cut herself off from home, and so keenly realised that she had bartered her birthright for a mess of pottage as bitter to the taste as the apples of the Dead Sea. When she had been further informed that Athanase was named after his grandfather, and Sosthène after his uncle, who were planters in the Isle of France, and that the good lady’s own name was Zéphyrine, an incongruity upon which she herself commented with fat chuckles of enjoyment, Alma at last ventured to say that she was tired, and would fain retire for the night.

“Ah! my poor child! That I should not have thought of it! And you are pale—pale as this linen,” waving a handkerchief that in the morning had probably been whiter. “Come; Nasi and I will show you to your room. Unfortunately, we have no spare apartment in the house, and it is really in the Custom House; but the bed is comfortable. You are young and tired and will sleep soundly, and in the morning early I will send round some one to you with a cup of tea. Come, chère enfant.”

They proceeded round the verandah to the other side of the house and through the long, covered passage in the garden that they had skirted on Alma’s arrival, then down a short one in the Custom House, into which doors opened from various rooms.

Under the closed door of one of them shone a brighter light than the dim oil wicks with which the building was scantily lit.

“That is where they are ‘working,”’ said Mrs. Bingham; “we will not disturb them—you are so fatigued, and I will wish them bonne nuit for you.”

She threw open a door as she spoke, and ushered her guest into a large, cool, bare room, with two windows, situated at right angles to each other, one of which was shaded by a drawn down venetian, the other, which was long and narrow and barred with iron, had neither blind nor venetian, so that the bright moonlight streamed through it, illuminating that part of the room and leaving the rest in darkness. Lighting a little lamp that stood on a table near the bed, which, with a washstand, a couple of chairs, and a strip of Indian matting on the floor, constituted the whole furniture, Mrs. Bingham gave a motherly kiss to the girl, while Nasi clasped her hand in his lithe, lissom young fingers.

“Bonne nuit! Dormez bien!” and they departed. Left to herself, Alma’s first act was to fasten the door and extinguish the little lamp, that was smelling vilely and aggravating her sick headache. Then she sat down on her bed, and tried not to think, but just to rest a little before undressing herself in the quiet, dark corner, swaying gently backwards and forwards with closed eyes, as if rocking her own lullaby.

At first, she could hear occasional faint snatches of talk, in which she recognised the voices of Mr. Bingham and his son, in an adjoining room. Presently, she ceased to distinguish them, becoming absorbed in the thoughts which crowded into her mind, whether she would or no.

How wretched she had felt on leaving Bristowe, and parting with the kind friends who had kept her with them after her husband’s departure. Mr. Thornhill, fine, honourable English gentleman that he was—if a little proud, as some people seemed to think. Who, after all, had more cause to be so? And his clever, brilliant wife, who would have held her own as leader of a “salon” in the most select set of London or Paris society. The interesting daughter of the house, too; a little satirical, a little reserved perhaps, but so proud of her mother, and so singularly free herself from small feminine foibles and vanities. A charming family, whom Alma had learnt to love. Why were all her affections and friendships to be torn up almost as soon as they had struck root? These kind people, under whose roof she was at this moment, were hardly like strangers, but she would have to leave them, too, the next morning, and so probably it would always be.

Footsteps along a passage and the shutting of doors here interrupted the course of her reflections. Evidently Mr. Bingham and Sosthène were returning to the house. Then came a tremendous clang, as if a heavy door had suddenly swung to, and Alma could even fancy she heard a lock or a bolt shot. It must be the door of the long passage dividing the Customs from the dwelling-house. And all at once she realised that she was shut out for the whole night in a strange, empty, solitary building, quite alone!

It was not a pleasant feeling, for she had never been brave even as a girl, and had become a nervous, easily-agitated young woman. So she thought she would undress as quickly as possible and, child-like, bury herself and her fears under cover of the friendly bed-clothes. But her hand shook so that she could hardly manage to unfasten her dress, and the obstinate strings of a petticoat got knotted and entangled to such a degree that she was seriously contemplating jumping into bed without any further attempt at divesting herself of her ordinary attire.

Hark! what is that? A sound of footsteps outside the window—a kind of cat-like tread of unshod feet, and surely a dusky shadow goes past, and yet another and another! Blacks! Her heart, which had been thumping loudly, gave a great leap and then stood still. She had come across a few of them in Bristowe, town blacks, tame creatures, who spoke English and begged for pennies. She had only just begun to tolerate the young gins, with their little brown picaninnies slung over their shoulders, but the old hags with their pipes and their dilly bags, and the spindle-shanked men with their hungry, wolf-like dogs and their waddies, had always remained to her objects of horror. She never could understand why “King Billy,” who wore a brass plate round his neck with the title duly set forth thereon, should be a persona grata at Riverview, where he was allowed the run of the offices, and quite failed to see what amusement the household could find in his mimic antics when he strutted about on the lawn. “Now, me Honourable William Thornhill. Wait; you see. Now, me Governor, Sir George.” But, at any rate, he was partially civilised and harmless. All the blood-curdling stories she had ever heard or read about savage atrocities came into her mind. She shivered where she sat, and her teeth chattered with fright. What did it matter if the window was barred? Why, if they were only to look in, if she saw a black face at the pane, she knew she should die of fright. For a moment she contemplated snatching up a shawl, a towel, no matter what, and pinning it across the window: but that would only attract attention. Besides, she could not endure not knowing what they were about; at all risks, she must see for herself. So she got off her bed and crept along by the walls until she came to the window, crouching down so that her head was on a level with the sill.

The sight that met her eyes paralysed her with terror, so that, fearful as she was of being seen, she could not move from her constrained position. The bright moonlight made everything as plain as day, and the fires which the blacks had lighted around the circle within which they were congregated in some numbers threw up lurid flames, and cast fantastic reflections on the painted and besmeared faces of the warriors, who were flourishing their spears and nulla-nullas, and brandishing waddies above their heads in terrible mimicry of real warfare. Their hoarse cries and fierce yells mingled with the discordant music and monotonous chanting of the gins, who were beating tom-toms and swaying backwards and forwards as they sat in the background, with eyes fixed on the pantomime of their braves. The mimic combat was succeeded by a dance, if possible, even more terrible, in which the fighting men became so many grinning demons, with countenances distorted by every vile passion, dancing through the flames and throwing up their arms with wild screams and sudden shouts of fiendish laughter, such as one could imagine proceeding from the devils torturing the damned in the accursed orgies of an Inferno. Alma could have screamed herself, but her dry throat was voiceless. Her temples throbbed violently, and all the blood in her benumbed body seemed to have concentrated itself in her head, which felt as if it would burst. She turned sick and faint, and suddenly losing consciousness, sank down in a heap on the floor beneath the window.

How long she had lain there she never knew, but when she revived all was silent. Shuddering, while she nerved herself for the effort, she once more raised herself to her knees and cast a fearful glance in the direction of the scene that had been enacted. No traces remained beyond the ashes of the extinguished fires, strewing the ground where they had been lit. But for that, all might have been a hideous dream born of her frightened fancies and fevered imagination. Her trembling limbs could hardly drag her to the bedside; but, reassured in a degree, though still quivering in every nerve, she was at last able to close her strained and aching eyes in a sleep of utter prostration and exhaustion.

Alma Belmont was young and strong in those days, however, and when she was awakened by the brilliant sunlight streaming into the room, followed by the arrival of the promised cup of tea, she was able to dress and appear at the breakfast table with very little trace of any more trying experience than the fatigue and indisposition of the previous evening. She had made up her mind to say nothing about it, being rather ashamed of her fright, for a little calm reflection had convinced her that her kind host would not have left her in a position in which she could have incurred any actual danger, that the ship was not far off along the quay, and that her alarm had been utterly groundless. She felt glad to have come to this decision when Mr. Bingham said he “hoped she had not been disturbed during the night by the antics of his black friends,” that they generally chose a night when the moon was at the full for the indulgence of their pantomimic diversions, and that he had given them leave to assemble when they pleased on the piece of waste ground adjoining the Customs enclosure. He was sorry he had not warned her, as she might have been alarmed by a sight that must be novel and unexpected to a “new chum.” To which Alma merely replied, with a smile, that his hospitality was quite on an Eastern scale in providing such entertainments for his guests, and that she certainly had to thank him for a new sensation.

But time and tide brought round the moment of departure. With a sob in her throat Alma bade farewell to the warm-hearted Creole lady, whose soft brown eyes rested on her through tears as she affectionately embraced her, and wished her bon voyage! She had not been allowed to refuse the offer of Nasi’s last new straw hat in lieu of the petit chapeau ridicule that had aroused Mrs. Bingham’s womanly concern for her “poor nose” and complexion; and thus equipped, and laden with fruit and flowers in a basket, and other trifles that might conduce to her comfort and recreation, she watched the little party from the deck of the steamer until a bend in the river hid them and the township of Ellenborough from eyes that were dimmed by grateful tears.

She never saw any of the family again, with the exception of the absent Hilarion, whose acquaintance she made about a year later.

But that, as Mr. Kipling says, is another story.

The pair on board the river steamer bound from a Northern township in Queensland to its capital were about the same age as far as years counted, and these might have been five-and-twenty. The young man had “lived,” to use his own expression. The woman had had five years’ experience of marriage—an unhappy one. She had been sobered and saddened by it, and in consequence, imagined that she felt very much older than she did, and mentally characterised her companion as “a remarkably good-looking boy.”

The first time she saw him she had said to herself that there was too much of the Greek god about him, and “very little room for brains in that small head”; but her indifferent glance had lingered a moment on the classic contour of a face and form that excited a warmer admiration in most women than their antique prototypes of Antinous or Apollo.

On his side he had noted this initial indifference, and a dominant expression of sadness on a naturally mobile countenance. But he had also seen that the gaze of the dreamy, grey eyes could quicken to animation, and that they lighted up even when the mouth sometimes remained set and serious.

He had heard about her from his own people, and others—of the unhappiness of her married life, and how it had been said at head-quarters that her husband would have lost his billet over and over, but for “that little wife of his, you know.” He had long wished to meet her, and chance had brought them together a couple of days ago.

They had at once taken up a position of frank friendliness towards each other, and he had talked a good deal of his aspirations and ambitions, to which she had responded with apparent sympathetic interest. Still, he did not feel sure of the kind of impression he had made, or if when they met in the society of the capital, the entrée to her house would be allowed him for any other reason than that of previous acquaintance with his family. In fact, he had not quite made up his mind—in spite of what he considered an extensive knowledge of women—in what category to place her.

At the moment he wanted her to go on shore with him, but did not feel at all sure of her consent, or of his own powers of persuasion should she refuse. It would be pleasant to have a ramble in the moonlight while the wretched little boat was coaling and dropping cargo and passengers; but he was hardly surprised that she demurred to the proposition when made.

“I assure you, Mrs. Belmont, it would be quite impossible for you to remain on board while they are coaling. You have no conception how it would annoy you, and the captain says he will be quite a couple of hours about it. What would you do?”

“Well, I thought I would go to bed, you know, it’s nearly ten o’clock, isn’t it?”

“But you couldn’t possibly go to sleep with the noise, and even if you half stifled yourself shutting down the port and drawing the curtain across your door, it wouldn’t keep out the coal dust.”

“So bad as that, really?”

“Oh! ever so much worse! Heat intolerable, men swearing, pandemonium itself! Do be persuaded for your own sake — everybody does. It can’t be helped that you happen to be the only lady on board. I’ll take such good care of you, and you cannot surely resist that moon.”

Mrs. Belmont hesitated. She had not been long in this semi-tropical country, she knew people did things “out there” they would not do “at home,” still, it did seem an outré proceeding to wander off till midnight in a strange place with a young man she had only known a couple of days on board ship. True, she knew his family, but this Hilarion Bingham had the reputation of being what was called “fortunate” in his relations with her sex, and it was notorious that her husband left her very much to her own devices—all the more reason that she should be more circumspect than a better guarded woman.

It would of course be very pleasant to leave the dirty, evil-smelling vessel for a couple of hours, and breathe a purer atmosphere in that glorious moonlight and the radiance of the Southern Cross—if only people wouldn’t say ill-natured things and make her position more difficult. Life was bad enough while they spoke well of her; what might it not be should they speak ill or even think it!

Some of these reflections must have made themselves visible on her countenance, for even as she turned to speak, the young man arrested her unspoken words—“Don’t vex your soul on the score of Mrs. Grundy,” he said with a smile, “it would be nothing out of the way, and even if it were, there’s nobody to say anything about it.”

“There are reasons”—she began gravely.

“There always are,” he interrupted. “We know all about that, Mrs. Belmont, and now that you have sacrificed on the altar of the conventions, and made your nice, proper little protest, you’ll come, won’t you?”

Before she could utter the rejoinder that came to her lips, a young man crossed the deck towards them, calling out as he advanced—“You’re going on shore of course, Bingham. I see the gangway is lowered, but it’s rather awkward for a lady. You’d better let him go first, Mrs. Belmont, while I follow you, and between us, I don’t think we’ll let you slip over the side.” The slight cloud that had contracted Mrs. Belmont’s pretty brows cleared off as she turned to the new-comer.

“What an observant person you must be, Mr. Young! So much more so than Mr. Bingham, for example, who never noticed that I was frightened out of my wits at the mere thought of venturing on that ladder.” She gave a kind of little shudder, and continued: “Let us go before my courage fails me again.”

Hilarion Bingham turned upon her a look half amused and half reproachful, and silently preceded her down the rickety kind of ladder with one narrow plank nailed lengthwise across the rungs which had been thrown from the deck to the landing stage.

“Easy to see they don’t lay themselves out for lady passengers.” said the other young fellow, who was following with both arms stretched out until his hands rested lightly on either side of Mrs. Belmont’s waist.

“I had no business to come on a cargo boat, had I?” she retorted with a little laugh, tripping over the awkward bridge with the careless ease of a child, and hardly availing herself of Bingham’s outstretched hand as she swung herself down on the quay.

Alma Belmont was not the sort of woman to put on helplessness with an idea of making herself “interesting,” and for all that Hilarion Bingham’s beautiful head was “too small for much brains,” he knew this much, and she knew that he knew it. The other simple youth was much flattered by being credited with superior powers of discrimination, and made a remark to the effect that he had sisters, and ought to know something about women, and that they always “liked a fellow to look after them, and that sort of thing, don’t you think, Mrs. Belmont?”

“We know that you want to look after one woman, at any rate,” interposed Bingham, “and I am sure Mrs. Belmont will not wish to divert you from your allegiance, so don’t hesitate about dropping our company at the corner.”

The three had been walking abreast along a straggling kind of street, consisting of a few stores or shops with a one-storied dwelling-house here and there sandwiched in between them. They were for the most part dark and silent, as if the inmates were abed, but at the first turning—the “corner” alluded to—sounds of mirth and merriment and the music of a fiddle came towards them, proceeding from a brightly-lighted house, from which a signboard was swinging.

“Well, good-night, then,” said Frank Young, stopping to shake hands with his friend. “They seem to be keeping it up still; I expect the bridal pair, though, will have made themselves scarce by this time—”

“And pretty Lucy will want consoling for the loss of her twin sister, eh, Frank? Good luck to your wooing, my boy!”

“Let me wish you good luck, too,” said Alma, holding out her hand with a charming smile and gesture; “I had no idea I was treading on the heels of a romance.”

The young man laughed as he again shook hands warmly with the pair, and walked down the street with glowing eyes and rapid, elastic footstep.

“Now tell me all about it!” cried Mrs. Belmont, turning to her companion; “is it the innkeeper’s pretty daughter, or who is responsible for that beatific expression on our young friend’s ingenuous countenance?”

“Pretty sister, and a really nice girl, Mrs. Belmont. You have been long enough in the colony now not to be surprised if, indeed, I say a charming young lady. Report has it that the brother was an Oxford man; he is at any rate a gentleman, and a capable one to boot. He transformed a low public into a respectable house of entertainment, which has completely altered the character of the district, and when those twin orphan sisters of his came out to him instead of governessing for a livelihood, they found themselves treated like young princesses.”

“And what of the bridegroom. Is the match a suitable one for this—young lady?”

Hilarion replied to the pause rather than to the question:

“Ah! I see you are incredulous. He is a very decent fellow, a surveyor, and there is plenty of work here for men of his profession. Young and he are starting together on a three months’ expedition into the heart of the country the day after to-morrow, I believe.”

“Poor young bride! A short honeymoon!”

“Yes, poor fellow! A short honeymoon indeed!”

There was a perceptible difference in the two intonations: a note of wistful regret in the woman’s; in the man’s a ring of impatience and some other feeling.

It was such a night as one sees only in the tropics, flooded in moonlight and as bright as day. One could distinguish the different shades of leaf and flower, the delicate pink of the oleander, the greenish white of the seringa bloom, the waxen hue of the magnolia; the air was full of soft sounds and mysterious murmurs, laden with nutty fragrance and the heavier scent of the datura and trumpet-blossom. They had walked on till they had left the scarce habitations behind them, and Alma felt as if she were in some enchanted place. There was an unreality about this luxuriance of beauty, in the midst of which Hilarion and she were walking together as Adam and Eve in the Garden of Eden; its very loveliness oppressed her, and she gave an involuntary little sigh and stopped short. They had come to a kind of gully with a range of low hills on one side, on the slope of which was built a solitary wooden house, shut in by a hedge of prickly pear that surrounded it. It was new and unbeautiful, the trellised sides of the verandah as yet bare of creeper or vine, and the front open to the gully. By the roadside where they were standing lay a tree log, and a small clump of trees still further back cast a kind of shadow onwards.

“Let us stop here,” said Alma; “we can sit down and speculate on that solitary, silent house, which would be almost ugly if it were not transfigured in this silvery radiance. And yet,” she continued, “I would sooner make my home there than go on, go back to—” she stopped abruptly with a quiver of pain in her voice.

“Yes, I know, everybody knows,” cried Hilarion; “go back to a man whose very presence is a degradation to your womanhood, to a life which must be one long endurance and martyrdom. “Why do you do it, you poor little woman? God, why do you do it?”

There was a note of passion in his voice that had not sounded till that moment.

“Stop,” exclaimed Alma, “say no more; for pity’s sake, stop, Mr. Bingham.”

She shrank away a little, putting up her hand as if to hide her face, but he caught hold of her wrist and grasped it firmly while he went on with a torrent of rapid speech that she was powerless to check.

“You shall hear what people say about this husband of yours: that but for you he would not have a single friend or acquaintance, that no one would receive him into their houses. Do you know that you could divorce him to-morrow if you chose? What should hinder you from doing it, and entrusting your happiness to other keeping?” His voice softened as he spoke, and he dropped the hand he had grasped and laid his own gently upon it. “Don’t sacrifice your whole life. He has himself disgraced the name he gave you. Cast it off, even if you accept no other.”

Alma turned upon him almost fiercely. “Do you think I should take back my own, the name that I never sufficiently valued, the name that belongs to my brothers, who sustain its honour in the service of their country? You must have a very poor opinion of me, Mr. Bingham, for I fear, indeed, I have brought this upon myself. Let us go back to the ship.” She spoke with dignity and made a movement to rise, but Hilarion gently restrained her, and her gaze followed his gesture as he pointed to the house on the hillside.

“Look,” he said, “look, we are in shadow and they cannot see us.”

A lamp had been brought into a room opening on the verandah, where a man and woman were standing close together, the moonlight full upon them. The man’s arm was round his companion’s shoulders, and one of hers, from which the loose sleeve of her white wrapper had fallen, was raised against the verandah post, her head resting on her hand; she was looking out into the night with a rapt expression, while his gaze rested on her face. For a few moments they stood thus like statues, marble-white in the moonlight, the pair below motionless as they. Suddenly they saw the man put his hand under the girl’s rounded chin and turn her head towards him, when she flung both arms round his neck and was almost lifted off her feet as he clasped her to him in a close, long embrace.

In a transport of passion Hilarion caught Alma to his heart with wild kisses that she hardly repulsed. The spell of the night was upon her, and the happiness of the wedded lovers throbbed and thrilled in her breast as in his, knocking at her heart with a clamant persistence.

“You love me, Alma,” he whispered; “look up and say you love me.”

As Alma raised her head, she saw the verandah was deserted, the lights extinguished, and the house once more in silence and darkness. With a sudden revulsion of feeling, like the snapping of a string too tightly strained, she burst into tears and thrust Hilarion from her with a cry—“How could you—how could you?”

The reproach in her voice stung him like a blow as she sank sobbing on the tree trunk from which they had risen, and he uttered no word of protest or appeal till she had grown calmer; then he said simply—

“Forgive me, Mrs. Belmont; I was wrong. You do not love me, but I—love you. Give me a little pity for my love.”

“Pity! I have none to spare. I need it all for myself. You knew it. You cannot expect that I should either pity or forgive.”

She spoke with the cruelty, the perverse injustice of a woman at war with herself and unable to resist inflicting her own suffering on another, jerking out her words like so many lashes; and thus Hilarion felt them as he stood before her with head bowed and eyes cast down.

In the curious mechanical way that we see objects with our bodily eyes while the absorbed mind looks inwards, he became conscious of watching what appeared to be a piece of stick lying in the dust at a little distance from Alma’s feet, and all at once it seemed to have changed its position and to be moving or dragging itself along the ground, till it had almost reached the hem of her dress. In a sudden he had realised her danger. Without a word of warning he lifted Alma up in his arms, and carried her some yards before setting her down again on her feet. As he did so, she struck him full in the mouth with the back of her ringed hand.

“How dare you? How dare you?” she cried furiously.

He had already gone back to the spot where she had been sitting, and was striking with his stick at a wriggling, hissing reptile. Then for the first time she realised the danger from which he had saved her. She was trembling from hand to foot when he rejoined her.

“Thank God you are safe!” he exclaimed, with an indrawn gasp of relief.

“I owe you my life,” she said simply, then suddenly cried out, “But you are hurt—what is it?”

His face was lividly white from emotion, and he was holding a handkerchief to his mouth; as he removed it to reply, she saw that his lower lip was cut and bleeding, and again cried out anxiously, “Oh! what is it?—what is it?”

“Curious!” he said, with a smile that she felt to be worse than any reproach—“curious how remorselessly women can break a man’s heart, and yet be pitiful over a drop of blood! There is no harm done, Mrs. Belmont. I was yours, and you have marked me with your brand—that is all!”

“And you saved my life!” She broke into a passion of tears.

“This is my reward,” he said, gently taking her hand in his and raising it to his lips. “I do not ask again for love nor pity—nor even for remembrance. If you think you owe me anything, give me your forgiveness. It is a compact, is it not? You shall forgive and forget, and I will forgive and—remember.”

He dropped the hand he held and waited, but Alma uttered no word. Moved by an impulse that she did not attempt to resist, she placed both hands on his shoulders and, with a grave tenderness that was almost a blessing, kissed him on the forehead.

“Goodbye, Hilarion!”

They stood a moment facing each other, looking each into the other’s eyes. Then Hilarion quietly drew Alma’s arm within his own.

“We will go back to the ship,” he said. And side by side—nearer rather than further from each other in spirit, since that mutual farewell—they retraced their steps in silence.

IT was drawing to the end of September, and the consequent close of the season at Beauplage. Still a fair sprinkling of subscribers were patronising the afternoon concert at the Casino, and a small group of English visitors sitting on the red velvet raised benches at the end of the room (a coign of ’vantage from whence to discern the entrances and exits of one’s friends and acquaintances) had been loud in their applause of a pot pourri of national airs played by the local band of the Casino.

“Do clap them for once, Mrs. Belmont,” said the girl of the party, which consisted, besides herself, of her brother and mother and the very pretty woman whom she was addressing. “That nice conductor is looking this way, and it’s his own arrangement, you know.”

“But I so abominate such hotch-potch productions, my dear child; there’s only one thing worse than these jumbles of airs, and that’s the single air with variations.”

“Well, I don’t like that myself, when it comes to practising time,” returned the bright-looking young English girl; “each variation always goes on getting more difficult than the other, and one never seems to have half enough fingers. At least, I don’t”; and she laughed out like the merry school-girl that she had only just ceased to be.

“Joyce is so delighted with everything,” chimed in the gentle, middle-aged mother. “This is her first visit to France, and I am afraid, when we go home, she will find Dulwich very dull indeed.”

“Very dull, which it is,” echoed the brother, with intention.

“Oh! please stop him, Mrs. Belmont; he means that for a pun, and when once he begins—”

But Alma Belmont was at that moment giving a little intimate nod of recognition to a big splendid figure of a blue-eyed Englishman who was standing in the doorway, stroking a pointed brown beard with an unconscious, habitual gesture.

“That’s the fellow who arrived yesterday, and a fine chap too! I saw him for a few moments last night in the smoke-room. Davenant, I think they called him. But he’s an old acquaintance of yours, I believe,” he went on, turning to Alma and following her glance as the new-comer bowed to the group with a slight comprehensive salutation.

“A very old acquaintance, Mrs. Marshall, and it may interest you to know that he ‘stroked’ the Brasenose eight over a dozen years ago, and could almost have stocked a silversmith’s shop with his cups and racing prizes, for he was a runner as well as an oarsman.”

“Didn’t weigh fourteen stone then, I should think! But you don’t mean to say he’s the Davenant? Why, he left traditions behind him, and I know a lot of Brasenose fellows who would give their ears to have a yarn with him. Being a Brasenose man myself, naturally—”

“Hush, Guy! for goodness’ sake don’t get so excited!” interrupted Joyce Marshall. “That was the last piece, and he’s coming our way.”

“We may as well go down to meet him,” suggested her mother, and presently they had all joined him and issued out together on the wide glass-covered stone entrance, and then through the gardens down the marble-paved port, Mrs. Marshall leading the way with her daughter, and Alma following with her double escort. When they had reached that windiest of all corners, known to the English colony as “Merriman’s,” Mr. Davenant paused and wished his companions good afternoon. He wanted to go in for a look at the English papers before dinner, he explained.

“See you in the smoke-room after dinner, I suppose,” eagerly interpolated the young man, but Mr. Davenant was afraid not; he had promised to join a small whist party after dinner, at the Consul’s.

“In fact,” turning to Alma, “when the dear old man heard I was returning to London to-morrow, he wanted me to stay on to dinner, and I could not get off without promising at any rate to look in to-night. He had kept me at the Consulate the whole afternoon until I strolled down just in time to find you all leaving.”

“Perhaps you don’t know there’s a dance on at the casino to-night,” said Joyce—“the last one too. Couldn’t you get away by eleven, Mr. Davenant?”

“I shouldn’t be any acquisition from a dancing point of view, Miss Marshall, having long given up such frivolities, and I hope to be getting some beauty sleep by that time,” he concluded, raising his hat as he stood on the doorstep of the library with a look in his blue eyes that was half grave and half quizzical.

Later in the evening, when the guests at the big Hotel-Pension were mostly gathered in the drawing-room after dinner, taking their coffee before sallying out again, Alma Belmont was standing by a long French window half-opened to the balcony, listening attentively to a man who was leaning against it outside.

“Strange!” Hugh Davenant was saying, “that after all these years we should both come back to the home of our childhood, the wretched little French town that we alternately abused and loved, and meet by chance in this caravanserai, then only to find you going about with a pack of uninteresting and commonplace people, and I hardly able to speak half a dozen consecutive words with you! The same old game! Well, History does repeat itself with a vengeance!”

“There are stranger things than that, Hugh!”

“One of them being—?”

“That you should still care—”

“Still?—always! Not that I was sure of it myself until I saw you again yesterday. And then it seemed only the day before that I had gone back to Oxford and heard of your marriage and departure for Australia, and all the old pain and grief came back again with a rush!”

“It seems a hundred years ago to me. Don’t let us talk about it. Why in all these long years have you never married, Hugh?”

“Et tu brute!” You can ask me now, now when at last I am in a position to speak, and you are once more free, Alma!”

“If that is what you want to say, old friend, don’t say it. My freedom is sweet to me, and I could never marry again; I was too unhappy.”

“But I would so surround you with loving care and devotion; if you had only a spark of womanly pity or common gratitude.—Pah! what drivel am I talking?” He checked himself suddenly, and she interposed with a kind of strain in her sweet, clear voice.

“Had I any pity or gratitude in those old days, Hugh, when your devotion must have won recognition from any girl less ungrateful and selfish and heartless than myself? I am no better now, rather a good deal worse, but I have thought sometimes that my unhappiness was a kind of retribution. You were so patient with me always, so kind and true, far more than I ever deserved.”

“If you think so truly, Alma—and indeed I have always given you the whole love of my heart—you can more than repay me now. Only give me leave to take back my old place at your side as more than friend, more than brother, your unacknowledged lover still if you will it so, but not altogether as then, hoping against hope some day to obtain a dearer title!”

He spoke in low, concentrated accents, which could have reached no other ears than those for which they were intended; and while the tardy reply was lingering on Alma’s lips, a voice near them broke in upon the momentary silence.

“Are you not going to put on your things, dear Mrs. Belmont? Shall we wait, or go on and keep a seat for you?”

“Thank you, Mrs. Marshall, I am coming; I won’t keep you ten minutes.”

“Then you will find us below in the courtyard.” Alma turned back to the man on the balcony.

“Hugh, dear old Hugh, don’t be vexed! I promise you shall have an answer in the morning. Give me a little time to think. Have patience with me!”

“I am not quite as long-suffering as I used to be, Alma,” he replied with a touch of bitterness. “One gets tired of playing for ever the part of l’un qui embrasse, while l’autre tend la joue—and not even that, by Jove! Don’t dare to play with me, Alma.”

There was in his tone as much of menace as entreaty. Never in his life had Hugh Davenant so spoken to her; had he done so in “the old days” their lives might have been very different.

Now, like the woman that she was, her reply seemed almost inconsequent.

“Hugh! If you only knew how I have longed for a sight of your dear old face, for a grip of that great brown paw!” True affection looked out of her eyes into his own, and his hand held hers for a moment in a firm clasp.

Then she said in the clear, level tones that characterised her utterance, “We both have our engagements to keep. Good-night.”

“It will be for me a long night till the morning,” he replied with gentleness; and not till he had watched her pass out with her friends through the big gates into the street did he leave the balcony that looked down into the courtyard.

Alma had told Hugh Davenant that the old days of which he spoke seemed to her as a hundred years ago, and as she sat in the brilliantly-lighted, mirror-panelled salle watching the dancers, all her youth passed in array before her mental vision. She saw herself once more a young, radiant, irresponsible creature, the centre of a throng of flatterers and admirers, grudgingly bestowing half a dance on one, unconcernedly sitting out half a dozen dances with another, either surrounded by Frenchmen, or discreetly left to a tête-à-tête with the favourite or the hour, and they were of all nationalities. Girls had envied, married women had been jealous of her, men had loved her to distraction; she had gone on her way smiling, intoxicated with her own fascinations and triumphs, heedless of what might be said or thought; and what had been the outcome of it all? Satiety, discontent, a reckless, unhappy marriage, exile, misery!

Absorbed in the past, her companion was unheeded until the return of Joyce Marshall with her partner recalled her to the present.

“Such a glorious waltz, dear Mrs. Belmont. How can you sit out? Guy would be so awfully flattered if you would take a turn with him, and Mr. Hume was asking me if I thought you could possibly be induced.”

Both young men eagerly protested in unison that they would be “so delighted,” “honoured,” but Mrs. Belmont was not to be persuaded, and they went off to make up their set for the Lancers then forming.

Joyce was not going to take part in it, and Alma announced her intention of going up to the terrace while mother and daughter were together; her head ached, the lights and dancers worried her, the sea air would do her good; they were not to take any notice if she even did not return to the ball-room, as she might possibly after a time stroll back quietly by herself while it was still early.

In the general move of young people seeking or claiming partners, she slipped out of the salle quietly but not altogether unnoticed.

A man who had been watching her during the evening without attracting her attention, had followed her out of the ball-room and up the shallow polished staircase, then stepped into the empty reading-room for a moment when she had reached an angle at which she would otherwise have seen him. He had styled her in his mind a harmony in ivory and grey. She had kept on the white serge skirt she had worn in the afternoon, with the substitution of a creamy befrilled silk blouse for the jacket, and she carried a long grey cloak over her arm. Her skin was the same dead white as her dress, and her grey dark-lashed eyes were ringed underneath with amethystine shadows.

When she reached the covered terrace looking out to the sea, she drew a chair close up to the railing, and was sitting down, when her cloak caught on some projection as she attempted to draw it around her; almost before she realised the obstacle it was deftly disengaged and placed round her shoulders, and a voice at her elbow caused her to turn round and face the intruder on her solitude.

“Pardon,” he said with the languid drawl of a petit maître, “but this is not the first time by many that I have been fortunate enough to render you this trifling service, though not to Madame Belmont.”

“Nor is it the first time either that I could have dispensed with the service, monsieur—in the past as now.”

“Unkind as ever, the same provoking Alma! Eh bien, tant mieux!”

“Impertinent as ever, the same futile Fouligny! Tant pis!”

The little Vicomte threw his head back and contemplated Alma critically, as if he were appraising a picture.

“Parole d’honneur!” he broke out at last, “you have lost nothing, except—and I am not sure you are not the more charming—your roses!”

“And you—have gained nothing, except perhaps —” and she looked at him through narrowed eyelids —“a stomach!”

“Méchante! My contemporaries are almost all married men, and keep good cooks. Que voulez vous?”

“And why have you not ‘ranged’ yourself during these fourteen years and married also?”

“A quoi bon? My friends have mostly married pretty or charming wives (which was very kind of them), and I endeavour to show my appreciation, hein?”

Alma gave a little contemptuous shrug of the shoulders.

“You are an incorrigible, Monsieur de Fouligny!”

“Ah, madame, why not have married that poor de Bassompierre who adored you, and remained to us?”

“As one of the charming wives? I do not share your regrets, M. de Fouligny. But jesting apart and in sober truth, I should be glad if you would consider this little entr’acte over. I am tired. I came here to be quiet.”

“I am mute, deaf, blind, whatever you would like me to be. I take this chair beside you and look in another direction till it suits you to recall me to life, then you permit me to escort you to your domicile. Is it not so?”

Alma made a movement of impatience.

“Vous m’agacez enfin! I need no escort; my friends are waiting for me below. I wish you goodnight.”

“Now indeed, madame, one realises that you have been amongst the savages. This is barbarity, but I obey.”

Standing up, he drew his heels together in a low, ceremonious bow, and was turning away when Alma held out her hand with her charming smile and gesture.

“Not half the mauvais sujet that you try to make one believe, mon cher. Are you not tired of the old pose? Take my advice and study a new character.”

“If you were here to coach me in the part, qui sait? Enfin bonsoir, madame.” And Gontran de Fouligny departed with a very creditable sigh, feeling for his cigarette-case as he turned in the direction of the smoking-room.

His inopportune appearance had disconcerted Mrs. Belmont, who had sought the solitude of the deserted terrace, not to bandy words in an encounter of wits with any frivolous Frenchman, but to dive down into her own heart and make up her mind as to what answer she should give Hugh Davenant in the morning. But the fact of once more conversing in the old familiar language had thrown her thoughts still further back into the past. She saw again the dark, grave face of the man who had been her girlish ideal, when, at eighteen—in love with Love itself, she had first met the man of thirty, who realised her every dream of what a hero of romance should be. The gallant soldier with an historic name, courted and beset by women of the world, to whose advances he opposed the shield of a calm indifference, had laid it down at the shrine of this innocent, girlish worship, but even he was powerless against the claims of la famille, that Juggernaut which can control the destinies and crush out the hearts of the sons as well as the daughters of France.

Alma loyally struggled against the flood of remembrance; she had risen from her seat and was leaning over the iron balustrade looking out to the moonlit expanse of water; the tide was high, and the swish of the waves against the seawall was distinctly audible. Suddenly, like the change of a slide in a magic-lantern, a fresh picture impressed itself upon her mental retina. In fancy, she was taken back to the shore of the great Australian tidal river where she had encountered Hilarion Bingham; they were together on the deck of the steamer, they were walking in the tropical moonlight of that enchanted Garden of Eden. His last words rang in her ears—“Alma, soul of my soul, farewell!” She cast a furtive glance around; so vivid was the impression that she almost expected to see the speaker. Then a feeling of anger with herself took possession of her, and she began to pace restlessly up and down until the recurrent sound of her own footsteps begat a fresh irritation. With an idea that any change might dispel the obsession of her reminiscent thoughts, she began to descend the polished steps of the staircase, and almost unconsciously found herself out on the marble pavements of the port before she realised that she had left the casino. The quays were deserted, even the cafés and restaurants seemed silent. She began to think that the hour must be much later than she had imagined, and instinctively drew the folds of her long cloak closer around her as if to efface her personality. She quickened her pace as a stray passerby cast a glance in her direction, then she fancied she heard following footsteps, but went on her way resolutely looking straight before her. At Merriman’s Corner a slight gust blew back the grey hood that covered her dainty coiffure and slightly bared throat, and as she was drawing it further over her head, the flash of the diamonds on her ungloved hand suggested a fresh cause for trepidation.

By the time she had reached the pension, her heart was thumping in her breast, and her one thought was to get in safe and unmolested. She had to pass the closed gates of the courtyard and turn down the side street in which her own quarters were located. When she had first arrived at the pension earlier in the season, it had been crowded, and a room had been assigned to her in a house through which a communication had been opened with the main building. Single people who did not care for large rooms, and those who merely required the night’s lodging without board were generally housed in the smaller building; but Alma had found her room comfortable, and had not cared to change it later. Now, as she fumbled nervously with her latch-key, she almost wished she had rung the porter’s bell at the big gates, but while debating as to going back round the corner and doing so, the key suddenly turned in the lock, and closing the door quickly, she fled down the long passage, up the dimly-lighted staircase into her own room as she imagined. She did not know that in her fright and nervous agitation she had gone a flight beyond her own landing until, on rushing in and hastily closing the door behind her, she confronted a man who was rising from a writing-table, and recognised Hilarion Bingham.

Her trembling knees gave way beneath her, she sank helplessly into the nearest chair, and could only gaze at him without a word of explanation. His own surprise also at first arrested speech or movement on his part, but presently coming towards her, he laid a hand on her arm with a gentle touch that reassured instead of alarming her.

Speaking as if he had seen her but yesterday, “You have been frightened, Alma,” he said kindly, as he quietly stood before her, “sit still and compose yourself, and then tell me if I can help you in any way.”

His composure partly restored her own.

“I thought I was being followed out of doors,” she answered. “I came in and rushed upstairs in such haste that I must have passed my own landing—my room is underneath. I must go down again.”

Her breath still came in short gasps as she spoke, and she looked round with a scared expression.

“You had better wait,” he said, “till I make sure there is no one about. I think every one is in except an Englishman I met to-night at the British Consul’s, my father’s old friend, with whom I have been dining. He said he would smoke a cigar on the leads before turning in.”

Even as he spoke, footsteps resounded and stopped at the end of a corridor running at right angles from Hilarion’s; then they heard the closing of a door.

“Better wait a little longer. I will look out presently,” he went on. “I am only passing through myself on my way to Paris, where I have left my wife,” he continued, looking steadily at Alma as he spoke, “and shall be off early in the morning. Tell me something of yourself. How comes it you are travelling apparently alone and unprotected?”

“I know every inch of the old place,” replied Alma, with a slight note of protest in her voice, “and—I have been a widow for some years. You are happy, I trust, Hilarion. Do you still live at—?”

He answered almost before she had completed the question.

“Yes. I succeeded to my father’s position when he died. Coralie is a niece of my mother’s who came out to us from the Mauritius, and who is a dear daughter to her.”

“I am glad,” returned Alma simply. “Good-night, Hilarion.” He looked out, and shut to the door for a moment as he took her hand in both his own. “Our little daughter is named Alma. You see I did not altogether forget. Goodbye; Dieu vous garde!

Once again in her own room and the light turned up, Alma sat down at a table without removing her cloak, and began to write rapidly. At last she stopped to read what she had written:—

“DEAREST HUGH,—I married a man I did not love; I have loved two men whom I did not marry. The one love you know of—a sentiment, a romance bred in a young girl’s imagination, heightened by obstacles, opposition. The other an infatuation that sprung up in a night out of circumstance, surroundings, the revolt of an unhappy woman!

“These books of my life are closed. If you care to inscribe your name on the third volume, I can still offer you a fair white page, and perhaps even a fresh heart. Quien sabe?

“ALMA.”

She changed her walking shoes for slippers, still keeping on her grey cloak, with the hood drawn around her head and face; once more mounted to the second landing, passed the doors guarded by pairs of boots on each side of the corridor till she reached the one at the end and thrust the note underneath it.

When she opened her eyes the next morning, the smiling femme de chambre handed her a note with her early roll and coffee. “The big Monsieur Anglais of No.20,” she said, “had given her the billet for madame. Bel homme, ma foi! et pas fainéant! He was then going out for a walk before the déjeûner.”

Alma hardly waited for her to leave the room before opening it. The envelope contained a man’s visiting card on which a few words had been scribbled in pencil, and there was an interpolation that read thus:—

“Come down ready to go out immediately after breakfast.”

“At last I have found my master!” she said to herself, and sprang out of bed with a smile of exceeding contentment.

Safe from the mountain tempest’s wild alarms,

Safe from the driving sea-wild’s bitter spray;

Placid, enfolded in the forest’s arms

Lies Pember Bay.

Did some known lover in his fancy’s youth

Name thee in accents musically slow,

Soft Papaitonga, “Beauty of the South”

Called long ago?

Midway between the mountains and the deep;

Secure from upland cold, from salt winds keen,

Bathed in sweet air and sunshine, thou dost keep

A golden mean.

Dark clouds may brood on yonder peaks and spurs,

Chill winds may chase the sea foam, flake on flake.

But here is peace. Nought ruffles, nothing stirs the tranquil lake.

Nought shakes the ferns, whose interlacing fronds,

Like sea-birds’ wings uplift their giant pinions;

Nought stirs the brakes, whose creepers’ myriad bonds

Guard green dominions.

Look, while the sunset clings to yonder range.

Look, while the lake gleams silver in its ray;

And pray that though all beauty else may change,

This scene may stay.

Here the wild birds from ancient coverts pressed,

May seek asylum by this silent mere;

And though no other glade or wave give rest,

May find it here.

Though in an hour the forest fire ends all

That nature can in patient ages build,

Though through the land the straight tall trees must fall,

The birds be stilled,

Yet in this sacred wood no axe shall ring,

These winding shores will sanctuary give,

Where in cool thickets happy birds may sing

And verdure live.

Still for the singers be thy tree-girt edge

And isle leaf-canopied a shrine secure,

Still for the swimmers be thy fringing sedge

A refuge sure.

Long, Papaitonga, may thy ferns grow fair,

Thy graceful toé-toé droop and sway,

And never tree or bird know scathe or scare

By Pember Bay.

A generation has slipped away since the Great Massacre, and even in this district in which I live, scarcely a hundred miles from the theatre of that abominable tragedy, the facts are almost forgotten, at least blurred to a fading patch of colour. It is remarkable how swiftly time passes; and what was yesterday a fear, to-morrow will become a reminiscence somewhat agreeable to talk over. Yet upon my mind are scored deeply the recollections of that horrible scene.

In the year of the Great Massacre I was in my eighth year, pretty sharp for a child, though somewhat undersized. My escape came about in this way. I had left Point Despair about eleven in the morning in the company of a lad, somewhat over my own age, who was returning to his people at Murimuru, some twelve miles distant. The road was plain and easy, running for some miles along the coast; moreover, living alone with my uncle, I maintained a certain licence in my expeditions. Consequently I asked no leave to slip forth and accompany this playmate a certain part of his journey. It was a bright, warm day; we had some sandwiches in our pockets, and there was the sea smiling with a thousand lures at our feet. The suggestion was irresistible; we stripped to the skin, half way to Murimuru, and idled most of the afternoon in the water. It was not until my companion was suddenly pricked by his tardy conscience, and marched off, declaring he must make Murimuru with all speed, that I turned to retrace my way to Point Despair. The road, as it reached the point, dipped into a sparse piece of bush, through which it twisted irregularly for a mile or more, and ere I had issued from its shadows the dusk had fallen.

It was not at once that I was struck by the singular quiet which ruled the flat, for I was occupied at the moment with lively fears about my length of absence; but half way to the post-house some uneasy appreciation of the stillness brought me up, and almost simultaneously I noticed a column of thin smoke rising at the back of Willis’s lean-to. With that the significance of the silence went out of my mind; there was plainly a fire forward, a most unusual event in our small settlement; and, my anxiety forgotten, I broke into a run, thrilling under the stimulus of a new sensation. I had barely passed the lean-to in the dull twilight when I stumbled and went sprawling over something in the pathway. The thing gave under me, shifting a little aslant, and I cannot tell you my sensations when I perceived it to be a dead body. The light was still sufficient to see by, and ere I withdrew with a pant of alarm and terror I recognised the face, which was now staring up at me, as that of Willis himself. The spectacle was horrible. I carry it still in my memory, as vivid and as ghastly as on that evening thirty years back. God knows how barbarously the wretch had been done to death, or perhaps the innumerable and dreadful wounds had been inflicted after the release of that poor spirit. My mouth fell open, and my eyes watched the dead man’s fearfully, drawn with a nameless attraction. It was the first time I had ever encountered death, and I had no power of motion in my limbs. My legs shook, I stood transfixed; the stare of those dead eyes held and terrified me. But presently the tide of reflection returned; I took my gaze from the corpse and let it go round the vicinity. I was alive now, on wires of fear, ready to jump off at an instant’s sound. But no noise came save the low, persistent murmur of the sea upon the shingle. Even then I had not conceived the fate which had fallen on the settlement. The horror had been so extreme that it had dulled my nerves, but as the blood flowed anew from my heart a certain reaction set in, and I was able to gather my wits together. I supposed that this Willis, who had never been popular with me for a sourness of temper, had met with an abominable accident, and that I was the first to come upon the tragedy. The news, shocking as it was in all the horrid circumstances of its presentment, roused in me an alacrity, and I hurried to be off. I turned from the still and stupid body, which as it lay had somehow a look of obscene importance, and I scuttled towards my home with all speed.

As I did so the dark and moving shadows of the column of smoke saluted my eyes once more. Vague and distant in my mind was a restless wonder of this appearance. I had a momentary presage of a wider fear, unintelligible but colossal, and then I was running for life with the terror of that defiled body at my heels.

The house in which I kept my uncle company was little more than a shanty, and lay about the middle of the four-and-twenty houses which constituted the township of Point Despair. The settlement held no street; it had not reached the dignity of order, and few of the plots were enclosed. A kitchen-garden, containing a handful of gooseberry-bushes, a few currant-bushes, and rows on rows of cabbages and potatoes, for the most part surrounded each dwelling-place. Macfarlane’s house alone had the luxury of a verandah, and was, in addition, fenced with posts and rails, against which grew a hedge of pinus insignis. Here it was that I stopped for the third time. For the front door, flung wide, was squeaking in the breeze, and a figure in a woman’s dress lay in a heap on the verandah.

The sight sunk me back into my abject fears. I would have fled past it on the feet of panic, had not a horrible fascination mingled with my terror. I had come direct from one corpse upon another. The bare fact of this sequence appalled and benumbed me, and yet once more I was drawn insensibly to inspect this second horror.

It was not so dark but I could make out every particular of that mangled heap. I remember that I pored over it stupidly, noting every ghastly detail, but comprehending little. My imagination suffered under a surfeit of the earlier horrors, and could digest no more. She lay with an arm clutching at her side; it may be she kept some secret in that final moment, or perhaps it was merely by an instinct of defence. I could peer at the body so, but I should have shrieked out to have touched it with a finger-tip. When I left the verandah I had no proper sensations and no settled thoughts save a desire to get home. So incapable was I of further impressions that the body of a child in the pathway conveyed no meaning to me, though I was conscious that its name had been Sally. I merely accepted it as a natural part of this strange and rather terrible condition. I stepped over the child, backed away from it cautiously, keeping my eyes upon it, and then swiftly resumed my former gait. It might perhaps have leaped upon me. I knew not what would happen.